Missing photo ID#131382

Jim and Laura McCarthy, Barbara Thatcher and I, climbing as two ropes of two, found ourselves on the summit of Steeple Peak with storm clouds brewing. For a moment we thought the buzzing sound was some loose material flapping in the gusts, or maybe even some kind of insect nest, but in a flash we realized the summit was discharging electrons and we were acquiring a positive charge, the lightning equivalent of a target painted on your back.

We quickly reinforced some old rappel tat with an extra piece of webbing an got the hell out of there, and not a moment too soon: rain and hail started immediately and lightning seemed to be striking everywhere, setting off large rockfalls and making us feel like we were in a WW II movie.

Huddled 150 feet under the summit, pelted by hail and hunted by lightning and rockfall, we discovered that we couldn't pull the rappel lines. (We were in such a hurry to escape the buzzing summit that we neglected to have the first person down test whether the lines would pull.)

Our situation was immediately critical. Hail and verglas were rapidly coating the rock, making even fourth-class terrain extremely difficult. Our ropes were stuck on the summit. The storm cells were coming in waves, with new and nastier versions appearing on the horizon all the time. And the lightning seemed to be striking everything but us---so far.

An instant passed as we contemplated our situation in dumbfounded silence. It was Jim who galvanized into action. "We've got to free up those ropes!" he shouted over the apocalyptic rumblings of thunder and stonefall. He slapped two prussik knots on the rope and proceeded to hand-over-hand his way up, pausing whenever he could let go to slide the prussiks up as protection.

This was a stunning performance, genuine heroics. Jim was heading to the only place more dangerous than the one we were in. It was clear that the slow methodical process of conventional prussiking on sodden ropes would leave us all exposed to further bombardment for a long time, and in spite of the obvious immediate danger, Jim made an instantaneous calculation that he could manage hand-over-hand and that it was the best thing under the circumstances.

The military gives out medals for heroism under fire. Jim certainly deserves one for his actions that day. He reached the top, rearranged the ropes rappelled back down, and we pulled the ropes.

After a slippery traverse, we faced a slabby descent, probably fourth to easy fifth class when dry, but now coated with verglas and hailstones. We could find no rappel anchors. Shod in smooth-soled rock shoes, we would have to downclimb this newly-iced terrain. Jim went first, a braced but unanchored upper belay from me his puny reward for the risks he had just undertaken. He climbed down 100 feet without being able to place any protection. Finally he found a sloping ledge and managed to fiddle in a single mediocre nut. This forlorn trinket was our belay anchor.

Laura and Barbara followed with tight upper belays, and then it was my turn. The icing had gotten somewhat worse during the three descents, and I looked down 100 feet at my three companions, huddled miserably in the storm, clipped to that one questionable piece. If I fell climbing down, I would surely take them all with me. There followed the most frightening moments of a climbing career that had had its share of R- and X-rated leads. Can anything be less secure than climbing down an icy slab? Nothing at all for the hands, a foot lowered down and placed, the weight transfer bringing with it instant total commitment with no chance of adjustment or recovery. It seemed like an eternity to me, and it might have been even worse for the three spectators whose fate was linked to my tentative and fearful movements.

Somehow, I made it to the "anchor" without slipping. We began to enjoy some spacing between the waves of thunderheads, some blue sky and even a sunbeam or two illuminating our way for a few minutes before the next cell arrived. These breaks and the lower altitude were enough to make the rock merely wet rather than iced, and we made steady and uneventful progress to the lush meadows surrounding Deep Lake.

The green alpine mosses greeted us with the moist fragrance of the valley, our stoves roared into action, water was boiled and infused, and the sun made a tardy appearance, painting the peaks with an alpenglow made more dramatic by the dark background of storm clouds scurrying off to the East.

Haystack reflected in Clear Lake

Visit on ggpht.com

RG Photo.

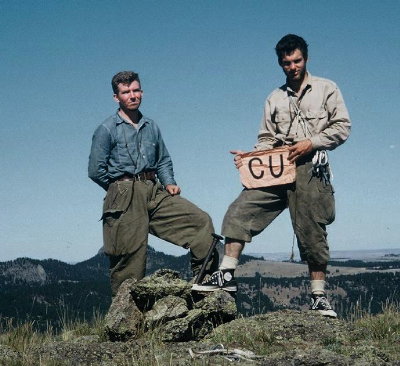

A shot of Mac early his climbing career, on the summit of Devil's Tower with Dave Bernays in 1954. (Jim is on the left and Dave is the guy with the tight pants.) Note the advanced footwear. Jim came back a year later to do the McCarthy West Face route.

Visit on climbaz.com

Photo on www.climbaz.com from the John Rupley collection.

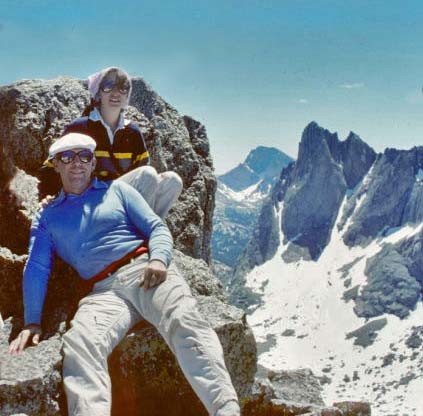

Jim and Laura in the Winds (on Pingora or Wolfs Head?) a year or two before our epic on Steeple Peak.

Photo cropped from Geno's SuperTopo post (where the area is misidentified as the Sawtooths).

Barbara Thatcher on a variation on the East Ridge of Wolf's Head. Steeple Peak can be seen in the background, appearing as a barely significant point beneath the bulk of East Temple peak.

Visit on ggpht.com

RG photo.

Jim and I, just slightly the worse for wear, at the Gunks reunion last Fall. (Burt Angrist to the right and Myriam Bouchard in the background.)

Visit on photobucket.com

Rick Cronk photo.

The original account and subsequent discussion appeared here in the Super Topo Forum. Thanks to Steven Grossman for posting what is now the lead photo.