It was mid-December of 1983. I'd gone to Nepal with Earl Wiggins to try new routes in winter conditions on Pumori and Nuptse. Pumori, at about 23,400 is an inspiring neighbor of Everest with an almost perfect pyramidal shape. Earl and I wanted to do a climb between the South Ridge, and the French route on the S.E. Spur. If we were successful on Pumori, we planned to follow up with an attempt on the huge, elegant and obviously difficult S.E. Spur of Nuptse East, whose summit is just less than 26,000'.

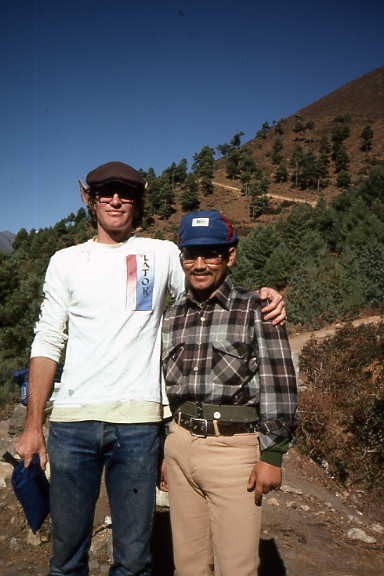

Earl and our sirdar on the walk in. Note the Spock ears Earl is sporting. We alternated wearing those to see the reactions of the Sherpas and porters as we passed. There were some classic double-takes!

Almost immediately our plans were thwarted when, the very first night after we arrived at our 17,000' base camp Earl developed a life-threatening case of pulmonary edema. In the middle of the night, the L.O., the sirdar, the cook and I started walking Earl down to Pheriche at 14,000, where we arrived just after dawn. At the little "hospital" there was bottled oxygen for Earl to breathe and a yak for Earl to ride as we continued down to a little Village alongside the Dudh Kosi at about 9,000'. After a night there, Earl was obviously out of danger, his lungs were clearing fast and he was breathing freely.

We had a discussion and decided that Earl would stay with the L.O. at his current location for 5 or 6 days, and then if he was feeling good, he could slowly make his way back to base camp, taking as much time as necessary. In this way we hoped he would not suffer a second bout of pulmonary edema, and perhaps even be able to climb higher. In the meantime our sirdar, cook and I would head back to our unattended base camp and wait there for Earl. Traveling fast, the walk back up to base camp took my two companions and me about eight hours of mostly silent hoofing.

We probably each had our reasons for not speaking much. Mine were primarily centered on the presence of some unsettling thoughts: Knowing Earl as I did, I doubted he would wait the full allotted time before starting to gain altitude again. I expected he would be back in base in probably half the agreed-upon time, raring to get up on the hill. I could then imagine the two of us getting three or four-thousand feet up the big face - then Earl's lungs would fill with fluid on some cramped bivy ledge - and I would be unable to get him back down the steep and difficult terrain. It seemed an all-to-plausible scenario. I decided the only thing to do was to quickly solo the mountain before Earl got back to camp, and hope to be able to explain my reasoning to him when he arrived.

The plan almost worked.

The day after arriving back in base camp, I packed the minimum of gear I thought I could get away with, and in the afternoon hiked the mile or so of glacial debris up to a bivouac at the bottom of the French SE Spur route, which I thought would be a safer solo than the gully and ramp system Earl and I had planned to climb. This five or six-thousand foot mixed rock and ice spur had only had one previous ascent ten years earlier by a strong team of Chamonix guides using expedition tactics. They strung ten-thousand feet of fixed ropes, established a number of camps, and spent more than a month on the mountain. I was hoping to climb up and down in three or four days.

The French SE Pillar is near the righthand skyline.

The first two days were great climbing on good ice and rock, never too difficult, but challenging with a pack. Just right for keeping the interest up and the concentration focused. At the end of day two I found a natural ice cave that made a commodious and sheltered bivy. Since I guessed this was at about 21,500', I figured it was high enough to leave my pack and bivy gear and sprint to the summit and back the next day.

The next day was a bone-shattering cold but perfectly brilliant winter day in the Khumbu peaks. Every ridge was precisely scribed against a sky so deep blue in contrast to the snowy cornices that the dividing line seemed laser-etched. The terrain now was mostly hard and glassy brittle ice. Front-pointing on the stuff was incredibly demanding - the previous two days' efforts also were taking their toll on my reserves. After gaining about five-hundred feet I began to have doubts as to whether I could make it to the top and back safely.

I was resting; leaning my head on my hands which were gripping the shafts of my tools; when out-of-the-blue I raised my head and said: "I'm pretty wasted, do you want to lead for awhile?" I turned to look back over my shoulder as if expecting to see my partner's face. Of course there was no one there - I was alone. My conscious mind registered that fact quickly with a small, embarrassed giggle. But my subconscious seemed to be boiling to the surface, more accessible than ever before, and in my uncommon rising awareness there was a warm and familiar - not quite identifiable presence.

Strongly, it was easy and natural to accept this apparition, which became my partner for the rest of that day and into the night. As I climbed I found myself describing to my unseen friend the moves I was making and the mental processes of the decisions I was taking. By the time I topped out on the face and walked the last few hundred low-angle meters of snow to the summit, the spirit beside me had become my solid support for what was turning into a massive effort.

We stood together at dusk on the summit, surrounded by a 360-degree ring of the world's most powerful mountains. We had a quiet one-sided conversation there; me talking, he listening. Soon a burning wind began to blow. "We better get moving," I said, "It's a long way back to the ice cave."

Night descended much faster than we did. It was dark already when we reached the top of the wall. We stopped so I could don my headlamp and uncoil the 200' x 7mm rope I'd brought for rappelling. Then began some of the most trying hours I had ever experienced in the mountains. The intense cold was sharpened into a cutting blade by the wind that whipped pellets of snow and ice all around, coming at this moment from that direction, a moment later from another direction. Where we could, we used old rock anchors left by the French. We hacked laboriously at the ice to cut a dozen bollards. It was all taking too long. We were losing core temperature to the frigid, star filled black night. We stopped rappelling and started down climbing. Periodically I asked my friend to be strong - to keep me strong.

It must have been about midnight when I stepped down and my left foot went into a hole. "We're here," I shouted, "we're at the cave". Shivering uncontrollably I removed my crampons and climbed into my sleeping bag as fast as I could.

Inside the cave, I shivered for a good half hour with no signs of warming up. "We've got to have something hot to drink", I said, and started fumbling with the hanging stove set near the head of my sleeping platform. I'd left it filled with ice chunks the previous morning, ready to go. I fumbled for the butane lighter I kept warm and dry in a chest pocket and after several shaky tries got the stove going. In ten minutes the ice was melted and I dumped the contents of a packet of dried soup into the luke-warm water and stirred it around. In another five minutes the soup was quite warm to my tongue, so I turned off the stove and set to getting the life-giving elixir down.

"Ohh, man that feels good", I said, after several long pulls from the pot. The soup was immediately sucked up by the tissues of my parched throat and the warmth as it hit my gullet felt like I had just swallowed the first rays of the morning sun. In another ten minutes I had downed the whole quart, then laid back contentedly for a few minutes more, literally feeling every cell in my body being re-hydrated and nourished.

Then things became awful.

I barely had enough time after realizing I was going to be sick, to turn my head away from my sleeping bag. Projectile vomiting began immediately. While I was still turning my head the vomit splattered an arc across the ceiling and walls of the cave. I don't know how long the retching continued, but when it was all over, all of the soup I'd consumed and any dregs of bile that could come up had melted a big hole in the floor of ice. "This is going to be a long night, my friend", I said. My words proved to be quite prophetic.

I hadn't slept at all when the entrance of the snow cave began slowly to take shape in the pre-dawn light. I felt like a fetus looking out of the vagina. I had absolutely no strength of my own to do what needed to be done. My spiritual friend was going to have to take on the role of midwife, and deliver me from the icy womb.

That must be exactly what happened.

Somebody pulled me out of my sleeping bag. Not me. Somebody shoved the things I needed into my pack and put the pack on my back. Not me. Then somebody forced me through the narrow entrance to the cave. Not me. I found myself facing the slope, standing on front points, my ice tools planted before me. The Sun was rising over Everest and its' rays were warming my back. We were all set to continue the descent.

"OK", I chattered to my partner, "Lets get down from here"

The descent from the ice cave unfolded like the petals of a miraculous flower opening to great the winter sun.

The first petal brushed my cheek as I started backing down the ice-face below the cave. That petal perfumed the day with the welcome smell of survival. The sweet scent cleared my brain of confusion and shocked me hard into the reality of what needed to be done. Carefully, step-by-step, I started the long process of down climbing...

Late in the afternoon I stumbled into a surprised welcome at base camp. The sirdar and cook came rushing up to grab my pack and hug me, ushering me home with true concern and happiness to see me. It wasn't long, however, before the sirdar handed me a note on a scrap of lined paper. The note was from Earl:

"Hey, Jello-

I felt good, so I came back up sooner than we planned. I watched through binoculars as you reached the summit yesterday. Congratulations! That's a beautiful big hill you've just climbed. I'm going to head up today and try to do the route we originally planned to climb. Should be gone about four days. If you want, I don't mind if you move base camp over to Nuptse. I'll catch up with you there.

But hey, would you mind waiting for me this time before doing the climb?

-Earl"

Upon reading this my heart flopped like a salmon caught in a net. This was way too fast for Earl to be back up in base camp, let alone starting solo up a giant Himalayan wall. But there wasn't much I could do about it. Earl was already somewhere up above at the start of his climb. It was almost dark and I was exhausted from my climb. I let the Sherpa’s feed me a little dahl-bhaat and tea, and then usher me to bed. Immediately I fell into a comatose, dreamless sleep...

One word, and one word only - "HELP!" - startled me instantly from sleep and that salmon began flopping around in my chest again. The cry had not been loud. In fact it seemed to have originated inside my head rather than coming in through the ears. One thing was certain, though - it was Earl's voice. But that was not possible. Earl was bivied over a mile above camp at the base of the face. Whatever the case, he had called for help, so maybe he had tried to descend in the night and he was close to base camp.

I roused the Sherpa’s and the LO. They hadn't heard a thing and were reluctant to get up in the middle of the night to go looking for a phantom. I insisted that we had to go find Earl. Finally they got up and gathered a few necessary things and we headed off in the direction of the mountain. Four headlamps bobbed and weaved an erratic course through the boulders, and shouts of "Earl, where are you?" were swallowed by the night, seeming to scarcely penetrate the vast space.

We had been searching and yelling for hours. Several times one of the Sherpa’s or the LO came to me and suggested that I couldn't have heard Earl, and we should go back to our beds. I had no doubt I had heard Earl, though, and insisted we keep looking. Eventually, we were getting quite close to the bergschrund at the base of the face, where Earl had indicated to the LO that he was going to bivouac. I began to despair that we'd ever find him, he really could be almost anywhere in all the vastness. There was just enough light from the stars that if you turned off your headlamp for a moment and let your eyes adjust, you could make out shapes and objects in the distance. I did this one last time to try and scan the line of the bergschrund in hopes something might clue me in to where Earl might have found a place to stay. Scanning back and forth, however, I could discern nothing. Feeling defeated, I turned around and looked back toward base camp...and the salmon leaped in my chest!

Not twenty yards in front of me; a car-sized boulder was backlit by a faint but definite glow. There was only one possibility, the Sherpa’s and LO were off to one side and behind me. The glow had to be from Earl's headlamp. "Over here, you guys," I yelled, already running toward the rock. When I rounded the corner of the big stone, there was Earl, lying curled on his side, the last photons from his nearly dead headlamp barely illuminating a frothy substance drooling from the corner of his mouth and making a dinner-plate size puddle around his cheek. I dropped to my knees to check for signs of life. When my face was a foot away from his, Earl made the best joke I have ever heard:

"What took you so long?" he whispered and weakly coughed. He was alive!

TO BE CONTINUED...

The Sherpa’s and the LO had arrived at the scene by this time. "Hang in there, Earl, we're going to get you down," I said. "Just stay with us, old man." Earl couldn't even stand, let alone walk. Time was of the essence if we were to save him. The only way to do that would be to get him down to a much lower elevation. I dispatched the LO to the nearest village, Lobuche, which he could reach in about two hours and hopefully get a yak and some man-power to help, there.

Earl had a nearly empty expedition-size pack on his back. I removed the Earl's pack and cut two leg holes in the bottom. Then the Sherpa’s and I loaded Earl into the pack, threading his legs through the holes. The sirdar took the first turn. The cook and I picked Earl and the pack up and held him in the air so the sirdar could slip into the harness. Then we draped Earl's arms around the sirdar's neck to help him stay upright, and the sirdar literally began to speed downhill using short quick steps. The cook and I stayed on either side holding onto the sirdar's hands to help with balance.

After about a quarter-mile, the whole procession stopped and I took my turn carrying the load. When I became too tired to efficiently do the job, the cook took a turn. And so it went for four hours. The night gradually faded and dawn turned to morning, the great peaks reassembling themselves on both sides of the valley, forming a massive corridor down which we struggled. struggled. For a while I tried to talk to Earl and keep him awake, but the overall effort became too great and eventually I just focused on the task of moving downhill.

The LO met us with help in the form of a yak not too far above Lobuche. As we thankfully loaded Earl onto the yak and secured him in place with webbing, the LO told us he'd tried to radio from Lobuche for a helicopter to fly from Katmandu and come pick Earl up. But he couldn't get the message through, so It was up to us.

Below Lobuche, the trail drops steeply down for several thousand feet to Pheriche. By the time we arrived in Pheriche, the doctor manning the little hospital was there to greet us with an oxygen tank and mask. The hospital hut was equipped with a hyperbaric chamber. It looked something like a small submarine with a little round portal to look inside. We loaded Earl into the tank, shut and sealed the door, then waited while the doctor brought increased the pressure in the tank, effectively decreasing Earl's elevation by another six-thousand feet or so.

The results were miraculous! Within an hour Earl was giving us the thumbs-up from within the tank and mouthing the words "Thank you!" The doctor felt Earl was out of immediate danger at that point, but felt Earl needed to stay in the chamber overnight to gain enough strength to continue the descent. Then the doctor showed me to a room with a bed and sleeping bag and assured me that he would watch over Earl for the night.

I went into the room, closed the door behind me, crawled into the sleeping bag, and passed out.

TO BE CONTINUED....

"Chai sahib? Chai sahib?".

Groggily I opened me eyes, sat up, and accepted the cup of tea from our cook (I feel guilty that I still haven't been able to recall his name). Leaning back against the wall I sipped my tea and reviewed the amazing sequence of events that had unfolded within the last week: Arriving at base camp, Earl and I full of piss and enthusiasm for our route. Earl getting sick and the first retreat to lower ground. My well-meant plan to climb Pumori and get down before Earl got back to base. Almost pulling it off, only to find Earl had already come back and was on his way to solo a new route. The knowledge that he had probably been goaded into action by my climb. Then the whole trauma of the second scare and rescue.

Personally, I had never been put to such a physical and emotional trial.

I finished my tea and got up to check on Earl. I was surprised to find him sitting on a low rock wall outside the hospital in the chill morning sun. He was wearing an oxygen mask and breathing O's from a tank, but his face brightened when he saw me and he raised his right hand in a sort of casual salute. He pulled the mask to one side and said, "Morning, Jello. I thought you were never going to wake up".

I sat down on the wall next to Earl. We talked a little, but there wasn't a lot to say. "You gave us quite a scare, lad," I said. "Thanks for rescuing my sorry ass," he said. Then we sat for at least half an hour, soaking in the sun and letting the details of a winter day in Pheriche infuse our senses.

Later, I ate breakfast and then had a shower in a little room with a bucket full of hot water draining from a dozen smal holes. It felt great, even though I had to get dressed in the smelly clothes I'd sweated and worked in for the last week. In the afternoon, Earl, with extra oxygen bottles and suckings O's through a mask - accompanied by the LO and a couple of Sherpas - began the trek down to Lukla, where he could catch a flight to Katmandu.

We hugged goodbye. It was the last time I would see Earl until a month later, back in the US.

Over the next week, the Sherpas and I went back to base camp, where we whiled away a couple of days waiting for a handfull of porters and yaks to arrive to help us transport our gear back out of the mountains. When I arrived in Katmandu five or six days later, there was a letter at the hotel from Earl explaining that he'd met a girl and they had gone off to explore the wilds of the jungle. All that was left for me to do before catching a plane back to the States, was to make my final report to His Majesty's Ministry of Tourism.

As the debriefing ended, the Minister handed me a stack of four or five letters that had arrived from the US while we were in the mountains. The third letter I opened was from my father:

"Dear Jeff,

I hope this letter finds you in good health and spirits. Your mother and I are wishing you all the best on this latest adventure. I can imagine how beautiful the Khumbu is at this time of year. Not too many tourists, and lots of cold, clear, windy weather.

I want you to know just how much you impress me with your committment and drive to do the things you do. You have chosen a hard path in life, but it seems as if you accept the difficulties that come with that choice. You can do the things you do because you believe you can. I can imagine the climbing on Pumori. Cold and steep. Brittle ice and intricate rock. I wish I was climbing with you.

My own health problems in the last few years have effectively squelched any more personal climbing dreams. I want to encourage you to do the things you want to do, now, and not put them off for some indefinite future. I also want to encourage you to continue to develop the side of yourself that loves people and cultures of all different stripes. It's diversity that makes life so interesting, and makes the planet spin.

Your mom and I look forward to hearing great stories upon your safe return home. Be sure to give our best to Earl.

Your ever-lovin' parents,

Ralph and Elgene"

At the top of the letter, Dad had put the date and time. After reading the letter once, I looked back to the top to check that date and time. My growing suspicion was correct. Accounting for the time difference between Utah and Nepal, Dad had begun to pen the letter at the exact same time as I had first turned to greet my unseen partner on the summit day on Pumori.

Dad was a solid companion throughout my life while he lived. He died four months after the Pumori climb, but his spirit still guides me.

-Jello