In 1987 my soon-to-be wife Betsy was waiting for word on our “1987 Nevada to Cho Oyu” expedition when she heard on the radio of an international incident involving rogue American cowboy climbers illegally crossing into Tibet. Yep, that was us. Our seemingly well-planned expedition turned out to be a mess with climbers one by one dropping out along the way, our expedition leader arrested by the Chinese Army, and an ugly tent fire incident. While recently going through my deceased Dad’s papers I found a dot-matrix printout of a write-up I had sent him of the expedition. I had written it two weeks after my return in 1987 and promptly forgot about it. Here it is:

After arriving in Kathmandu and Trekking for a few weeks with Betsy, we met with the Mountaineering Division of the Nepal Ministry of Tourism and were told that the Messner route which we were planning to do, and for which they had already granted permission months before, was in a sensitive area in which there had been border disputes between Nepal and Tibet. The route itself had been determined to be in Tibet and therefore was now off limits to us. They asked us to pick another route on the Nepal side of Cho Oyu, however we were not prepared or experienced enough to put up a new route on the steep north walls of the mountain. Faced with forfeiting $50,000 and an enormous amount of time and energy, we decided to go ahead and sneak into Tibet like the previous two years expeditions on Cho Oyu had done. They had apparently gotten caught and it would be hard to get away with that in any case since a Nepalese liaison officer accompanies all expeditions as far as base camp, but these previous expeditions had only received a verbal warning from the Nepal government.

After a week of red tape, negotiations, and required payoffs (apparently the government officials get paid little and depend on bribes to supplement their income) in Kathmandu, we took a fantastic mountain flight into the short dirt airstrip at Lukla into the foothills of the Himalayas. An example of the red tape and hassles:

We had paid $1,000 for a charter plane to carry our equipment up to the Lukla airstrip. We managed to get most of our equipment out of customs (some food was pilfered somewhere in customs) and out to the airport only to have our flight cancelled 4 days in a row. Our equipment was left on the ramp and we had to hire security guards to constantly watch it. Of course they give the pilot the authority to cancel the flight if the weather looks threatening. On the 5th day the weather seemed unquestionably clear and we were looking forward to getting going. Then our pilot asked through an intermediary for $300 or he would cancel the flight due to weather. We were mad as hell but we knew we really did not have a choice if we wanted to keep on schedule. We paid.

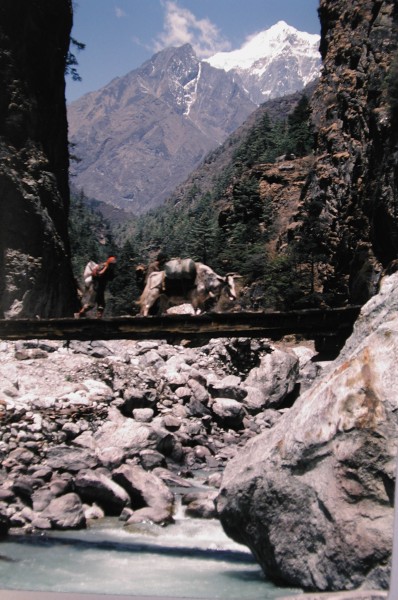

In Lukla, our staff of 5 Sherpas hired 35 yaks and 12 local porters to carry our food and equipment for the 10 day trek to the Cho Oyu base camp. For these 10 days and the time spent at base camp, the Sherpa staff would set up tents for us, cook local foods, and melt snow water. We did not plan on using Sherpas above base camp, but we paid one experienced Sherpa an equipment allowance and put him on retainer so that he could be on stand-by in base camp and could be used in an emergency on the mountain. It turned out later that he did not use the money to buy any of the necessary mountaineering equipment and would be worthless to us on the mountain.

The trek in was very pleasant as we went slowly in order to acclimatize to the increasing altitude. The highlight was on a side trip to the Tengboche Monastery near the stunning peak of Ama Dablam. On the way I passed up an elderly gentlemen struggling up the trail with a Sherpa accompanying him. I looked back and was stunned. “Sir Edmund Hillary?” I asked. Yes, he said. We chatted and walked with him a bit and then pressed on. At the monastery we discovered dozens of monks lining up to wait for him – it was a planned celebration for all Sir Edmund had done for the monastery and for Nepal. It was an emotional event, even though we stayed back since we weren’t exactly invited participants.

We had one scare on the main trail in - when the yaks and their handlers abandoned us when it snowed and covered up what little grass (yak food) there was on the barren ground. We wondered if we would see them again but they reappeared three days later with stacks of hay on some of the yaks and we were on our way again.

We knew we were following an ancient trade route between Nepal and Tibet but did not realize that it was still being used until I stumbled upon the dead body of a Tibetan trader who had tried to cross the glacier perhaps a little too early in the year. He was dressed in tennis shoes and a tattered old jacket with a bundle of goods laying nearby. He had apparently died of exposure after making it most of the way to the nearest Nepali village of Thame. The Sherpas kept their distance but the porters, being quite poor, tried unsuccessfully to get the fellow’s wrist watch off using a stick. We were to later see Nepali and Tibetan traders crossing the glacier pass Nangpa La in cheap tennis shoes while using yak hair across the eyes to block the sun.

We arrived in base camp, 17,500 feet and immediately starting carry loads up to camps 1, 2 and 3. Camp 1 was in Nepal and camp 3 was our advanced base camp at the foot of the mountain in Tibet. This advanced base camp was at an altitude of 19,500 feet and was soon fully stocked with extra food, fuel, tents, medical kit, and tanks of oxygen for medical use only (we would not be using oxygen to climb). By this time our team of 7 climbers had shrunk to 4.

One climber had shown up at the airport in Reno and announced he was not going because he hadn’t prepared enough. Our “team doctor” was an ER doctor who because of scheduling left late and inexplicably didn’t take the time to acclimate on his way up to base camp. He arrived a few days after we did, starting coughing up blood, and left. I heard later in the trip he met a girl while recovering down lower and decided he had probably missed the climbing and that he would rather go trekking with his new companion than come back up to base camp in a support role (for which he would have been needed).

We all got various forms of illness but one climber had dysentery so badly from eating the local food (mainly rice, potatoes, lentils and curry) that he became too weak to acclimatize to the altitude. He did stay in base camp in a support role for the remainder of the expedition.

Three of us remaining climbers were ascending a rocky ridge to camp 4 above advanced base camp when two members of the Chinese Army carrying large curved swords arrived in camp below us and arrested the lead-climber and expedition leader, Bob, who at the time was struggling to get his overboots on. Although they could not speak English these soldiers made it clear they planned to take him to Lhasa, Tibet and then on to China. We could see there was a major problem below us because the two soldiers were dressed in brown and obviously not climbers in bright colors. At one point Bob walked towards the base of the climb and waved his arms for us to continue. We did, and hoped we would soon see Bob but we never did.

They took Bob and while hiking down the hilly moraine on the Tibet side with the Chinese, Bob envisioned spending months in a Tibetan or Chinese prison and made the decision to attempt to escape even though they had his passport. Bob let the men get somewhat ahead of him and then turned and ran into the small rock piles of the moraine and then up the glacier. The soldiers pursued and Bob thought he would be quickly caught because he had to slow way down due to the altitude. However, when he looked back he saw the soldiers were stopping often, bending over and breathing hard. It seems he was probably better acclimatized than they were. So it became a slow motion foot-race at 19,000 feet and fortunately for Bob he won.

But not a total victory because the Chinese Army came back and every last bit of food and equipment was taken from our critical advanced base camp except for one folded tent they over¬ looked under some rocks. I do not know whether they realized the risk they were putting the climbers in who assumed the shelter, food, fuel and medical supplies were waiting for them at the base of the mountain.

The 3 of us on the mountain, Matt, Kirk and myself, spent the next 4 days climbing, carrying loads and establishing camps 4 and 5. We waited out bad weather for a day at camp 5, and then pressed on over the most difficult climbing on the route to camp 6 up a steep ice-fall. At the top of the last steep section of the ice-fall, I had unwisely unroped and walked ahead a short distance on the upper ice field to look for the route. I stepped over a snow-ridge which I thought may have been hiding a small crevasse and to my shock found there was a crevasse and it was wider than my stride. The next instant I was up to my armpits held up by my backpack, which was wedged between me and the icy blue wall. I put my crampons against the far wall and scrambled up and out of the crevasse and lay panting out of breath near the edge. At an altitude where taking a small drink of water can leave you breathless, the 5 to 10 seconds of total effort to get quickly out of the crevasse left me gasping for several minutes. The episode left me a little unnerved so I was thankful that Matt and Kirk agreed to call it a day and camp right there, leaving route finding through the crevasses for the next day. I also discovered to my dismay that I had smashed the lens on my camera which I kept on my hip when I broke into the crevasse.

Matt was not feeling well the next morning because of the altitude and the three of us got together to decide what to do. This put me in a slight dilemma since I had promised Betsy that we would not under any circumstances split up. However, there was a rope fixed back to the last camp where there was a tent and stove already set up. It would be fairly easy for Matt to descend the fixed lines, get into the tent and melt some snow to rehydrate then rest and wait the several days for us to reappear on the way down. So we split up.

Matt successfully descended from camp 6 to camp 5 and was lighting a propane/butane stove in order to melt snow for water when the entire tent was engulfed in flames. The seal on the stove had apparently frozen or wasn’t quite sealed and had been leaking in the tent for quite some time. Matt started for the zipper on the door but then just dove outside when the door disintegrated in front of his eyes. He rolled in the snow to put himself out but not before feeling a searing pain on his hands and face. His thick cold weather clothes, cap, and 30 days of not shaving protected most of body but the back of his hands, forehead and cheeks were seriously burned. Now Matt is injured, alone, dehydrated and without a tent.

Matt immediately started down and spent the day in a rush descent to advance base camp for medical attention and water. By now Matt was also becoming dangerously dehydrated, the first step towards hypothermia and shock. That evening Matt walked into advanced base camp to find it deserted, except for one folded up tent which probably saved his life. He slept in the tent that night and the next day forced himself to walk the normal 2 day trek over the glacier to the staffed base camp. That night Matt stumbled into base camp barely able to walk. Besides the burns, exhaustion, and the lack of food and water in the last 2 days, Matt complained of a pain in his chest that developed during the last few hours of his trek and was worried about his heart. He spent one day in base camp drinking fluids and then a Sherpa escorted him on a two day walk to a medical clinic near Namche Bazaar and funded by Sir Edmund Hillary.

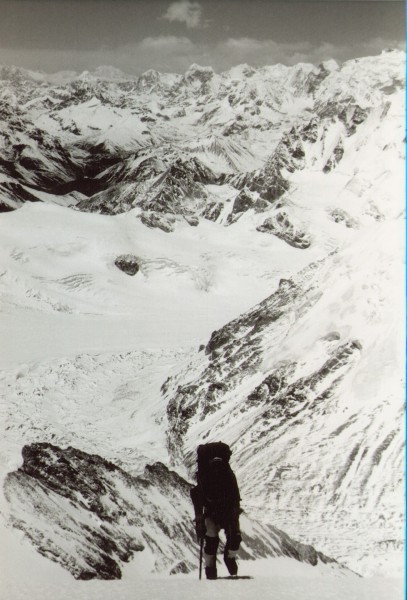

Meanwhile Kirk and I, the youngest and most inexperienced members of the team, had continued on and struggled through deep snow and glare ice and we finally reached a rock band at about 25,000 feet where we established camp 7, the final camp before the summit. There wasn’t enough room for the entire tent but with the tent draped over a large flat rock there was enough room inside for the two of us.

We were both moving very slowly, taking time between each step to gasp for air. It took a depressingly long time to cover any ground even though we knew that without supplemental oxygen it would be impossible to go much faster. In addition, Kirk had developed a dry high altitude cough that was starting to worry us. We had also lost our appetites, very common at high altitude, and were mainly living on fluids such as soups, tea, sugared drinks, and special carbohydrate drinks. Large quantities of fluids is crucial to high altitude survival and we spent a lot of time in our tent melting snow for water.

We were within 2,000 vertical feet of the summit at camp 7 and all we needed was one day of clear weather. We had planned to get up early and make a bid for the summit taking only warm clothes, water, a camera and a rope. In spite of feeling weak, we knew that no one feels real chipper at 25,000 feet and we felt confident that we could put in a long day and summit. The wind buffeted the tent all night that night and we slept poorly but arose early to prepare in case the wind and snow let up. By sunrise we gave up hope for that day and stayed in the tent all day. Around 3:30 pm two very cold and tired Chileans appeared (we had seen them on and off throughout the expedition) and we shared the tent with them for the night although it was extremely cramped and no one slept much, if at all. We all arose at 3:00 AM, melted snow and took turns putting our climbing gear on as the rest huddled against the tent walls to make room. We were all pretty good friends by now and we were making jokes, shoring up each other's spirits, and mentally preparing for the summit bid. However at 7:00 AM it was still a complete white-out outside with a full blown storm raging. Our summit hopes were crushed as we knew we were becoming too weak to stay at that altitude to wait out the storm. We made the decision to descend and recover to try again later (we still thought we had extra supplies at advanced base camp).

It was snowing and still blowing hard as we prepared to descend. We were both feeling pretty weak after two nights at 25,000 feet without oxygen. I struggled with my overboots and finally thought with somewhat foggy thinking, “hell with it” and left the toes of the wool insulated overboots sticking up. The upper ice field didn’t have any crevasses so we decided to descend unroped to save time. I didn’t take but 10 steps before I stabbed the toe of my overboot with the opposite foot’s crampons and sent myself head first on my side down the slope. I was sliding off-route, straight down a steepening ice field and it seemed like I picked up speed instantly. I was very thankful for the training I had done before the climb, because before I could consciously think about what I was doing, I was twisting onto my stomach and digging my ice axe into the hard snow for a purchase on the ice underneath. I then put my chest and all my weight on my axe and eventually came to a stop. I was too winded to move for a while, which left Kirk with the impression, looking down the slope at my body, that I was dead. We got that straightened out, my overboots firmly attached and on our way again.

That day was a blur of peering out through goggles at pure white blowing snow as we concentrated on finding the next bamboo route wand, ice block or other land mark which would tell us which way to go. We used an extra rope in the icefall because of the danger of being blown off while traversing the wall between the ropes already fixed there.

We had heard from the Chileans that Matt had been in a tent fire but the seriousness of it really sunk in when we arrived at camp 5 and there was a circle of nylon, most of it melted, partially covered in the blowing snow. That night the wind persisted and relentlessly pounded our tent, frequently knocking off frost accumulating on the tent walls. The fearsome noise, the lack of sleep, the "snow" falling in his face, and the pressures of the climb really built up on Kirk that night. Kirk is the nicest guy and I had not heard him swear before, but I woke up frequently during the night to screaming profanities. I was worried about him but I knew the only thing to do was to get off the mountain, and we were trying.

The next morning Kirk was feeling weak and his cough was still getting worse. We headed down past a previous camp and had a little trouble on a portion of the route that had been loose rock but had since iced up. Like Matt, we arrived that evening at advanced base camp at 19,500 feet to find that it was completely empty with the exception of one pile of equipment covered with a blackened down jacket. It was Matt's, he had taken everything out his pack that was non-essential to his survival in order to lighten his load. With the realization that we had no tent (we had left ours above and Matt had taken the one left at advanced base camp) or fuel for water, we solemnly added to Matt's pile. We were in trouble.

I had held it together and had taken the initiative to lead the way down the mountain but the realization we did not have a tent, that it was snowing hard, and that we may be too weak to sleep out without shelter was too much. I just stared at where I had personally stored a tent and supplies and couldn't bring myself to leave or do anything. Kirk kept telling me we had to go, that it was going to get dark soon.

We both thought our only chance was to find the Chilean's camp. They had told us previously that they had put up a tent in the ice folds of the glacier (either intentionally or surreptitiously hidden from the Chinese). We wandered along the edge of the glacier and just as it got completely dark we happened on their tent located quite majestically between two huge ice blocks. The Chileans had just arrived, having retreated in the same storm, and gladly invited us in. After probably spending a combined total in excess of $100,000 between the expeditions, neither of us had a pot in which to melt snow in. We finally found an empty can and spent much of the night trying to rehydrate ourselves.

The next day we thought we were going to have to hike the great distance to base camp but were extremely happy to see Bob waiting inside the Nepal border. I had been a little miffed that no one was at advanced base camp to support us as planned, but I soon understood. After Matt barely made it to base camp and told of the loss of our equipment, Bob had decided to set up the new camp in case we needed help but he didn’t want to venture inside Tibet. We were very glad to hear that Matt had made it back and seemed to be OK. I arrived exhausted but Matt had been in worse shape with severe dehydration and burns on his face and hands and he had hiked much further than we had to.

We hiked down to base camp the next day and spent two days rehydrating and eating rice and potatoes. We then did the trek down to the tourist village of Namche Bazaar where Matt was recovering. He was doing well and within a couple of weeks almost all the scabs and dead tissue had come off leaving unscarred skin underneath. We had all been dreaming of "real" food for weeks and everyone had lost quite a bit of weight so we ate incredible amounts of food for 4 days and had a great time while we waited for our mountain flight to take us back to Kathmandu.

The Chinese had filed official complaints so Bob had a lot of explaining to do when he went to the US Embassy to get a new passport and in fact is still in Nepal waiting for a passport as I write this at home in California on May 18. The Chinese also filed a complaint with the Ministry of Tourism and we are expecting a penalty, maybe a mountaineering ban for us all. It seems that China and Tibet, open to tourists and mountaineers for only a few years, are actively pursuing the tourist trade. Mountaineering is relatively big money for such poor-countries as Tibet and Nepal so Tibet apparently has decided to defend its territory so that they get the peak-fees, not Nepal. The route had originally been done from Nepal, the famous climber Reinhold Messner climbed the route from Nepal, and many other expeditions also have attempted the route from Nepal. I have a feeling we may be the last one to attempt it from that direction.