Around 1974 or so Jimmy Newberry and I teamed up with John Pearson and Scotty Gilbert to have a go at the North face in the winter. Skiing in with 85 lb. packs was brutal, but we had the minersí cabin to take the edge off the winter camping. Scotty and John went up the central couloir between the north face of Blanca proper and the north face of Ellingwood. This is the sanest line on the north face, which is probably why Jimmy and I went up the buttress to its right. The rock on Blanca is weird metamorphic amphibolitic and granitic gneiss that fractures in odd, blocky patterns that lack regular crack systems but yields a plethora of small, downwardly sloping ledges. When covered with snow itís a completely ridiculous surface to climb on. Here I should note that picking this line right of the central couloir was one of the more foolish route choices I have made on a major climb, and I typically am an overachiever when it comes to foolishness. We were several pitches up the buttress and things were getting steeper and weirder as there was nothing to get any pro into. After a full rope length of no pro whatsoever I could see a ledge about 15 feet higher that would give us a good belay. I yelled at Jimmy to pull his anchors and start simul-climbing so I could reach this point of relative safety. Jimmy was not amused. Once we were reunited at the belay ledge Jimmy reported that he had dropped one of his gloves on that pitch, which put us in a guaranteed major frostbite situation. We made several raps off some of the worst anchors I have ever used, usually a sling around some protuberance that had to be weighted just so to stay in place. There is no doubt that Jimmyís dropped glove saved our bacon. Scotty and John made it up their couloir but got benighted, then got lost on a descent that took them over the top of Ellingwood and down a ridge to the northwest that cliffed out. A helicopter from Ft Carson saved two lives that day in one of the most impressive shows of rotary-wing airmanship I have ever witnessed.

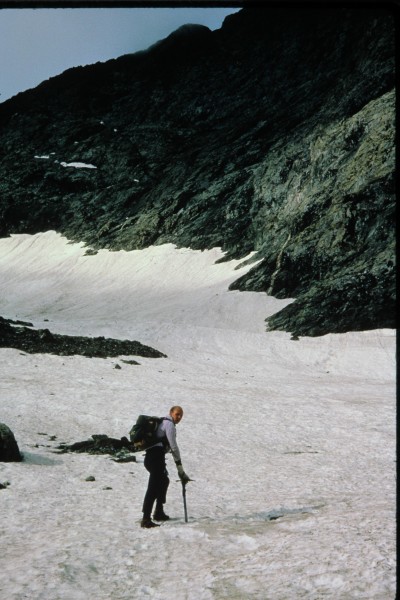

The following winter I went back to the north face of Blanca with Mike Dean. This time I decided that a direct line up the center would be just the thing. On this approach there is a lower cliff band of one or two pitches, a large snow-covered slope, and then the main face itself. We were up one pitch on the lower cliff band when Mike confessed that he was in over his head and completely psyched out by the north face. After the previous winterís debacle I recognized good judgement in a partner when I saw it and we baled.

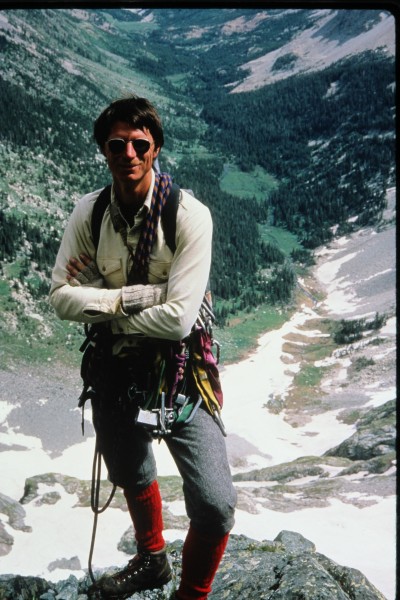

Fast forward to the mid 1980ís and a rational approach up Huerfano Creek in July with warm temperatures, long days, and magnificent fields of wildflowers. Really, people, this is the way the mountains ought to be enjoyed. Peter Dea and I put together a delightful route that used a series of discontinuous ledge systems leading to a diagonal crack system to get about half the way up the face. This led to a snowy chimney leading up into a shallow dihedral that ventured right for several pitches to the ridge just below the summit. The climbing was no harder than 5.8, there were a few old rusty pitons to show we were not the first, and protecting with nuts was quite reasonable. Cloud cover was descending to the summit just as we arrived, which only added to the atmospherics of the whole climb. The descent down the central couloir in foggy conditions completed our grand adventure on the north face that day. To top off a perfect day we returned to camp before the sun had set, which was a shocking departure from my usual modus. This climb, coupled with other solo trips up the northeast ridge and back down the central couloir during other summers had given me a reasonable appreciation for the geography of Blanca Peakís north face.

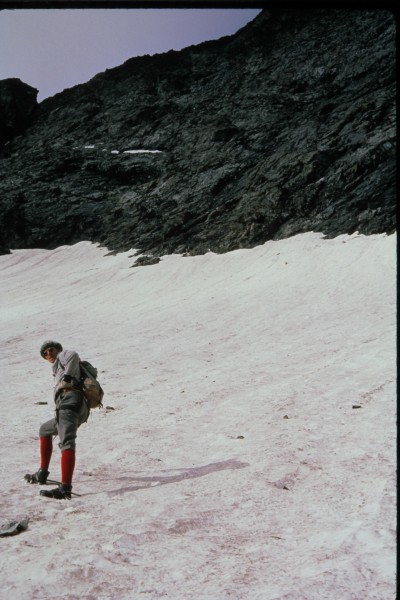

What is it they say about crazy, about doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different outcome? Early in the 1990ís I convinced my long-time partner John Ferguson that another go at the north face in winter was just the thing. We planned from the start to ascend the central couloir so only needed to take one rope and a very modest rack for the cliff half way up the couloir. Scotty Gilbert had taken a fall on that cliff but did successfully lead it on his second try on their ill-fated climb many years before, and I had rapped down it from some old pitons and manky slings on previous summerís outings. The ski in was just as long as on previous trips, but the snow was great and our packs were somewhat lighter. By this time the old minersí cabin had burned down due to some USFS-induced ďlightning-causedĒ fire, so we set up a tent to serve as our base camp. John and I skied as high up onto the face as we could get and found a ledge of sorts that we could dig out for a bivy at around 12,600 ft. It was early March, but with modern clothing and gear we stayed pretty warm throughout the night. Well, I did. Apparently Johnís feet never warmed up so the following day he elected to ski down to base camp rather than flirt with frostbit toes. I thought I might be able to solo the central couloir and headed up. It was a clear day with high winds from the south blowing spindrift off the top Ė quite the alpine atmosphere for what was shaping up to be a nice day of winter mountaineering. I quickly gained the cliff band in the couloir and was faced with a choice; the right side of the cliff was only about 15 ft tall, but overhanging and swept by spindrift avalanches every few minutes. The left side was about 30 to 35 ft. high and leaned back a bit, but had the typical outwardly sloping ledges with a thin veneer of patchy ice, not thick enough to get really good ice tool placements, but thick enough to make a guy think it had possibilities. I had a rope for the rappel but not enough of a rack to get solid anchors for a protected solo lead, and the couloir was very steep just below the cliff Ė no chance at all of a self-arrest. After repeatedly working up to the crux moves on several variations, I just could not commit with so slender a margin of error. I backed off and post-holed my way back down the couloir, filled with the lightness of being that comes with the pardon of a condemned man and secure in the knowledge that I would see another sunrise. John and I reunited at base camp, brewed up many pots of tea, and feasted on what rations we had left. The next morning yielded fabulous late winter skiing down Huerfano Creek by two guys who were just happy to be intact. I have not been back to the north face since. Iím OK with that.