by PAUL HUMPHREY

(Reprinted from article published years ago in the North Coast Journal.)

My friend Hiko Ito, 22, of San Diego, hung from the lip of a three-foot roof of rock 60 feet up an over-hanging cliff. The former Arcatan grunted as he strained to make one more move that would lead to a resting place. His feet dangled free in the air, and I could feel the rope that connected us shaking from the strain as he struggled not to fall. I was trying to pay attention.

If he were to fall, I was responsible for locking off the rope to stop him. It was hard to stay focused, though. I was being harassed by hungry mosquitoes and flies, batting them away with one hand as I held tightly to the rope with the other. Being surrounded by poison oak did nothing to help things, and I wondered if that was a tick or a freckle on my leg.

Hiko whimpered as he finally moved up into a secure position and looked down to see me wildly swatting at my insect hell. "Are you paying attention?" he asked "I'm getting tired."

I looked up and couldn't help but laugh. In addition to the bug repellent and sunscreen we had both lathered up that day, Hiko was also sporting a fine layer of Calamine lotion to stop the itching of a previous poison oak encounter. With his eyes bulging from the strain of the climb, and the gray film covering his arms, he looked like some strange aboriginal man in ceremonial paint.

"Hey, Hiko!" I hollered, "We do this for fun!" He laughed, turned back to the rock, and completed the climb without falling.

This might not sound all that fun to you, but despite the hazards, we were having a blast. We were rock climbing at a beautiful limestone cliff in the middle of the woods. The sun was out, and Hiko had just completed a climb that had never been done before. He rappelled back to the ground and found shelter beneath an oak tree. There we ate lunch, talking about meeting at Moonstone Beach the next evening for our regular bouldering session.

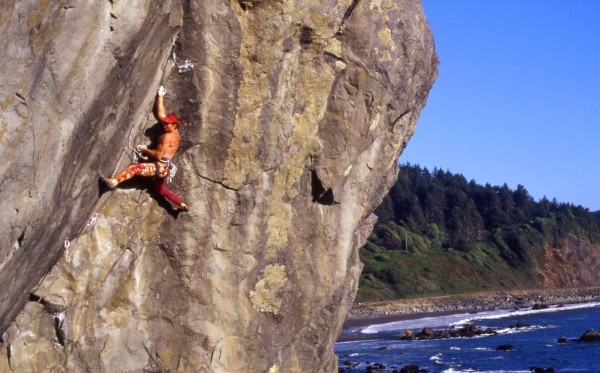

Moonstone seems to offer something for everyone. Surfers float offshore, waiting for the next wave, horses trot along the bank of Little River, and other folks simply sit and watch. Climbers also use this beach extensively, scrambling all over the boulders and setting up practice routes on the main bluff, called Karen Rock.

Legend has it Karen got its name from grafitti, a love message that once marred its face. Those words are long faded now. Fortunately for the rock, climbers prefer to leave only gymnastic chalk, and civic-minded climbers with wire brushes have removed other unwanted paint jobs over the years.

Moonstone is the gateway to local rock climbing. Its closeness, coupled with accessible and varied routes, makes it the place to go if you are looking for climbing partners or simply want to hang out. Some days so many ropes are hung from the bluff that it looks like climbers are trying to tie it down.

Like many residents of the North Coast, this beach is one of the first places I ever climbed. Day in and day out I would make my pilgrimage. I tried my best and studied more skillful climbers. One of them, Dana Laughlin, took to bouldering at heart. He moved like he loved the sensation of moving unhindered by a rope. I watched him for a month of evenings as he effortlessly climbed a problem called "Skyhook." This climb required that he literally leap from his position on the rockface to a hand hold just out of reach. It was dramatic to watch, and it inspired me to master that climb myself.

When climbers see a cliff face, they begin analyzing it for a sequence of hand and foot holds that will allow for an ascent to the top or another end point. Different climbers often come up with other routes up the face. Because of this, a cliff like Karen Rock has dozens of climbing routes, contributed and named by many climbers over the years. Information about these newly found sequences of movement is shared with other climbers, and if the sequences prove popular, they may eventually be catalogued in a guide-book.

Climbing routes are often named. It's easier to ask people if they've climbed "Launch Toast" than to ask about "the far left-hand corner at the north end of the beach with the small overhang at the top."

The need to communicate clearly about routes their secrets and hazards has led to the development of a vast vocabulary of slang. I was once talking with some friends who don't climb. When asked how my weekend went, I responded with a flurry of pantomimed movements. "Yeah, it was killer! I did this 5.11b route, an arete. The crux was a full dyno from a 1/2-inch crimp. I thought I had blown it, but I just hucked for it and stuck it! After that , it was just sloper, pocket and then, mantle out."

My friends stood there smiling politely, trying to pay attention. "You have no idea what I'm talking about do you?" I asked, surrendering to their bewildering expressions. "Just keep nodding,"one friend said to the other, which answered my question completely.

Up the road from Moonstone is Houda Point. Although located literally just around the corner, this tide-dependent beach often seems deserted in comparison. With a tide book in hand, a climber needs only a pair of climbing shoes and some motivation here, since most of the formations is made up of boulders. If the ocean is out, and the sun is shining, Houda is a playground.

When climbers scramble on the boulders, they are usually trying to find the easiest way up. But when climbers Boulder (with a capital b), the object of the game revolves around looking for the hardest way up. The goal is to explore the art of gymnastic movement, learning the nuances of climbing close to the ground where injury is not as likely.

Houda Point fits the bill, at least when the sand is up. The boulders here vary in quality from solid rock to not-so-solid. There's even a category of rock that's not advisable to hold onto. These uncertainties and varied conditions help prepare climbers for the challenges of route finding and rock assessment if they venture onto the more committing "lead-climbs" of the area.

If you have only seen climbers at places like Moonstone, you have probably seen them top-roping. This is a method by which a climber reaches the top of a formation by a trail and sets up an anchoring system to safely climb on with a rope. With that, those who climb the route will always have the rope overhead, limiting the length of any falls they take.

Lead-climbing is more of a committed activity. The climber starts at the base of the cliff and climbs up, trailing the rope beneath him. As the climber ascends, the rope is secured to anchor points along the way. The climber's partner feeds out rope through a special friction device during this process. If the climber happens to slip and fall, the partner locks off the rope to limit the length of the tumble.

Even so, the lead-climber is in for a ride, since he will fall over twice the distance he was from the anchor point below.

To illustrate this, imagine a climber has placed a piece of protection five feet below and then falls. The climber will pass the point in mid flight and will be caught about five feet below it, for a total of about 10 feet. Obviously, this excitement is not for everyone. But for a dedicated climber, leading a climb is often the ultimate goal, since it closely simulates the sensation of moving unaided over the rock.

Some local climbers never feel the need to lead, or if they do, just occasionally. They are content with the picturesque pocket beaches and crags scattered between Moonstone and Trinidad.

Others seem to have a thirst for a wider range of local climbing which is harder to quench. These folks go everywhere, looking around every point and headland for some hidden treasure of stone. The entire coastline from Arcata to the Oregon border has been explored, bouldered and climbed for many years. Guarded by long drives, river crossings, high tides, and other factors, the cliffs of the far North Coast are often more challenging than the crags around Trinidad. That's fine for those who visit them. The added challenge is welcome, and the views and positioning often overlooking the ocean make for an exciting day out. Just make sure you are up to the challenge.

The coastline is not all there is to climbing in our corner of the world. In the past few years, limestone has been discovered high in the local mountains. This rock is often a perfect medium for climbers, since it offers bizarre and puzzling hand-holds. The stone itself is remarkably solid, something the coast lacks.

I remember when I heard a rumor about limestone cliffs inland. I hopped in my car with my wife, Marcella, and off we went. "Just a short drive," I told her. "Up into the hills to check on something. It won't take long."

Four hours later, the car overheated for the fourth time on logging roads above Burnt Ranch. The temperature hovered above 100 degrees in Willow Creek, and my short drive was turning into the search for the Holy Grail. Marcella did not share my excitement. She was hot, dusty and ready to go home. "Just one more curve," I said for the fourth time. Luckily, the cliff was just around the bend.

The discovery of that first limestone cliff opened my eyes. Ever since, I have expanded a search for climbing inland from the beaches. In the past two years, over five new cliffs have been found. This presents enough potential for high quality new, worthwhile routes to last for many years.

These finds have led to the start of a mini-renaissance of Humboldt County-based climbers. It's not that many more people are climbing here, but the ones who do seem to have stepped up their involvement a notch. Local climbers are challenging themselves more. They are taking the time to drive to weekend areas in the hills, and head to the beach both for sunsets and bouldering after work.

Eric Chemello, 30, of Arcata, is one climber who has taken up the challenge, establishing new routes both on the coastal sandstone and inland limestone. Some of his climbs rate close to the top of the scale. Once, I helped him put up a climb called "If" (rated 5.13c in climbing language). The way Eric attacked it we should have called it "When." Later, on a variation of that route, I watched him take 15-foot falls, again and again, day after day, trying to link just two moves together. But the tenacity is the name of the rock game. Sometime after the 20th attempt, he got it and climbed to the top.

Climbers who call Humboldt home do so for more than the rock. After all, there's no other place like it. Climbers live and play here for the sunsets and the camaraderie. They climb because pursuit of the sport itself draws them out for a walk through the redwoods to find routes. Looking for climbing is a great excuse to simply explore more. I, for one, am having fun and learning northern California like the back of my hand.

Even though it might look like they're trying to kill themselves, most climbers are cautious by nature. They have to be. Mistakes mean more than losing the game. I had a climbing mentor who taught me the ropes, and I still believe this is the best avenue to learn climbing. If you have questions about what climbers are up to, ask them. Just remember, there are no stupid questions.

If you want to give climbing a try, start small and close to the ground. Build skills on the boulders before applying your confidence to higher cliffs. Remember, it's not the fall that hurts, it's the landing. Choose yours accordingly.

Take a lesson. Center Activities at Humboldt State University provides climbing instruction, and retailers such as Adventure's Edge in Arcata and Northern Mountain Supply in Eureka offer a wide variety of educational materials on the subject.

PHOTO CREDITS:

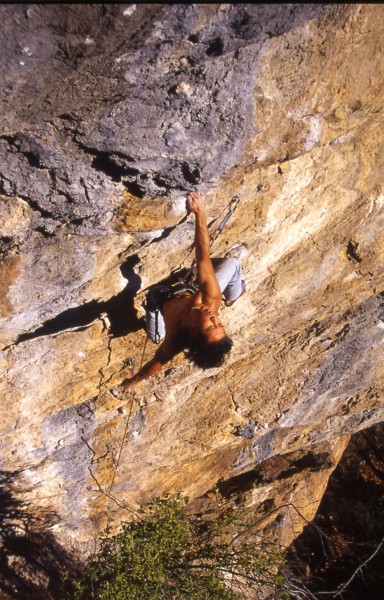

Top photo by Sean Leary: Eric Chemello navigates and negotiates a climing route called "If," a limestone wall near Burnt Ranch rated 5.13c -- difficult.

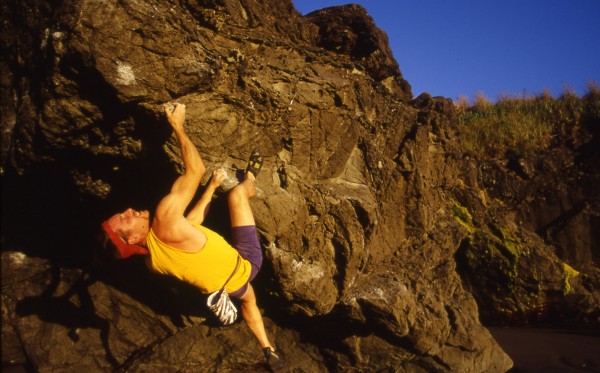

Second photo by Sharilyn Clark

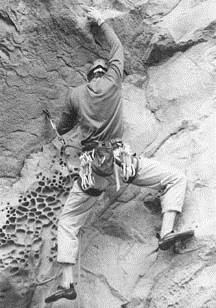

Third photo by Jeremy Newman

About the Author

by Susan Wood

CLIMBER EXTRAORDINAIRE Paul Humphrey, 27, Arcata, has a persistent bout of AAD "ascension addiction disorder," he calls it.

When he's not climbing the walls or exploring new routes on the North Coast, he's writing about it as a frequent contributor to the national climbing magazine Rock & Ice. The magazine is one of several outdoor adventure publications sold at Adventure's Edge, the Arcata outdoor gear store where he works. Someone with an inflated ego may be tempted to try to impress customers with that sense of authority, but it isn't Humphrey's style at all. The man exudes a pure, undaunted passion for his sport and the place where he hangs out to practice it Humboldt County.

Just listen to this passage about his 1993 initiation to climbing on Elephant Rock, visible to passing motorists off U.S. Highway 101 near the Westhaven exit south of Trinidad:

"The day I put up my first climb, I sunk deep into this addiction," he wrote in Rock & Ice. "No doubt the area was unpretentious: a crumbling, 80-foot cliff, forgotten in a stand of alders next to the highway. Sophisticated climbers would probably call it a pile, but having uncovered it and kept it all for my own, I thought it was a godsend."

He continued, describing his vertical progression, complete with grunting, groaning, scraping and scratching to get anywhere, only to be forced by exhaustion to return another day. The next assent, with the help of a final primal scream, he finally lunged over the edge.

"For a brief moment, the rush was perfect, the drug (the endorphin rush he calls AAD) took over, and I could no longer distinguish myself from the rock and moss through which I moved," he said. These few, zen-like moments in time even silenced the whirl of log trucks passing nearby, he recalled.

Although he's still prone to "laughter, bad puns and good beer," Humphrey has tamed the monster within since those early days at the peak of his addiction, he said. He's found more of a balance in his life, devoting more time and not in this order to his cats and his wife, Marcella.

"She makes me wear a rope above 20 feet now," he said, flashing a boyish grin while scrambling on Moonstone Beach one recent evening.

Humphrey and other eco-conscious climbers have become increasingly concerned about the environmental impacts of their sport.

From Nepal to the playground of Joshua Tree, Calif., some climbers, in their single-minded pursuit of the top, have gained a reputation for disregarding the environment.

Humphrey was once disturbed by a slide show that displayed an obvious scara limestone climbing route in Mexico that could be seen "all the way across the valley." Instead of being happy about the navigational advantages of such a disclosure, he questioned whether that was a good thing.

In the current issue of Rock & Ice he writes an educational piece about low-impact climbing, climbing with minimum impact on the environment. Humphrey's tips included ways to camouflage bolts and anchors, for instance.

The advice is timely. Just weeks ago, the superintendent at Joshua Tree National Park one of the most popular climbing spots in the world and climbers ended a year-long battle over whether the climber's safety, in permanently planted protective gear, or the environment's untouched nature is the priority. Both sides agreed on a plan that requires permits to install new bolts and lifts restrictions on replacing old ones, the Associated Press reported.

Comments? E-mail the Journal: ncjour@northcoast.com