The arid, Sierra air felt distinctly warm that evening, saturated with the scent of granite and Ponderosa Pine. I chose a more direct, rocky trail and carried most of the gear while Enock followed a more circuitous path, bypassing the most uneven terrain. We waited patiently at the bus stop, catching our breaths after hastily shuttling equipment down the trail. I aimed my headlamp beam towards Enock, as the bus approached making sure the driver would see he was in a wheelchair and thus would know to lower the handicap ramp. Enock had just finished training at the Laconte Boulder, a popular formation in Yosemite National Park utilized by climbers practicing rope ascension and aid-climbing technique, and we were waiting for the bus-shuttle back to Camp 4. In addition to assisting Enock with his dream of climbing El Capitan, I was also filming. After spending the past few days with Enock, I had familiarized myself with the nuances of navigating a wheelchair in Yosemite (what terrain to avoid, where Enock could efficiently wheel himself, and where I needed to offer a hand). I began looking at the Valley through new eyes - where wheels could and could not go.

Enock was born with a birth defect called Spina Bifida. He is paralyzed from the waist down and uses adaptive techniques to climb without the use of his legs. For the past few years, Enock has participated in the Paradox Sports adaptive climbing program, and with the help of Sean O’Neill, fellow sit-climber, and other Paradox Sports volunteers, guides, and participants; Enock has been training to climb El Cap. After a month in Yosemite, Enock returned home. He considered the trip a success, but it was not without significant setbacks. This project relied on the help of a lot of generous people who went out of their way to help Enock accomplish something very special. As with any audacious, worthy objective, adversity is natural – after all, these objectives precipitate from passionate people and from passion arises emotions with potential to engender tension. However, a mature team recognizes the value of estimable objectives and people and finds resolution. On this adventure, we did exactly that, and I speculate the adversity made Enock’s experience even sweeter.

Last winter, Enock’s training was delayed after suffering a severe infection from frostbite on one of his feet. It was so severe that some of the doctors involved were encouraging amputation. Enock’s dream of climbing in Yosemite was jeopardized. Fortunately, after undergoing a strong month-long antibiotic treatment, Enock’s leg was spared. Unfortunately, due to his prolonged healing he only had a small training window. With Yosemite fast approaching, Enock expedite his training with the help of Sean O’Neill. Sean is paralyzed below the waist and has extensive sit-climbing experience under the guidance of his brother Timmy O’Neill. Sean’s accomplishments include a few ascents of El Cap, the first paraplegic ice ascent of Colorado’s Bridal Veil falls, and an ascent of Devils tower just to name a few.Sean has also contributed extensively to sit-climbing innovation. In collaboration with other climbers, he developed sit-climb aiding techniques utilizing mechanical advantage daisy chains. In 2013 Sean used this technique to complete the first paraplegic lead-climb.

A few days a week, Enock traveled to Sean’s house in Maine to practice fixed line ascension on Sean’s property. Enock would ascend, and then Sean, belaying from his wheelchair, would lower Enock back to the ground. They would repeat this process over and over again. Sean would offer Enock suggestions, and Enock would test his advice on the following lap. With Sean’s connections to the adaptive climbing community, Enock was able to assemble a climbing team prior to arriving in Yosemite. Everything seemed to be lining up perfectly - almost too good to be true.

In early September, Enock arrived in the Valley with the goal of climbing Zodiac, a steep big-wall climb on the right side of El Cap. His tentative climbing team drew from a variety of folks deeply committed to his mission. Enock would spend the next couple of weeks participating in a Paradox climbing event and training for Zodiac. He and the team would hold off on the climb until I arrived two weeks later. Unfortunately, prior to my arrival, Enock encountered a series of setbacks. During the Paradox climbing event, his adaptive climbing-systems were not working efficiently. Enock’s performance was

disconcerting to the climbing team. The energy keeping this project going began to loose steam, and Enock’s preparedness and commitment were in question. Climbing a big wall is a substantial undertaking even with able-bodied climbers. Bringing a sit-climber up a wall is downright daunting. Assisting an unprepared adaptive climber on a wall could be considered cavalier. This definitive moment changed the tone of Enock’s trip and his support network waned. He felt alone, without direction, and his chances of climbing a wall were jeopardized. By the time I arrived in the Valley, Enock appeared dispirited.

This was the first time I traveled to Yosemite without access to a car. I flew into Fresno and took the YARTS bus to the Valley. I arrived with limited climbing gear, just my personal climbing kit and camera equipment. Most of the climbing logistics, including gear, were to be taken care of by the rest of the team who were local and able to accept that responsibility. My plan was to simply show up, plug-in, and join the climb. While my priority was to film, I would also be assisting Enock on the climb and sharing the lead climbing if necessary

In light of Enock’s shortcomings with his ascension technique, the team adapted and switched the climb from Zodiac to something smaller, the Prow on Washington Column - The idea being that the Prow would serve as a training trip for a bigger climb on El Cap the following year. Soon there after, there was discussion of downgrading once again to an even smaller multi-pitch climb, one with a short approach and less commitment for everyone involved. Enock was frustrated because the current objective did not reflect his expectations. He was still motivated to climb a wall, but was at the mercy of everybody else. While I understood the logic behind downsizing the objective, I empathized with Enock. He had worked so hard to make it to Yosemite. He overcame significant setbacks including almost loosing a leg. After healing, training, and traveling across the country to Yosemite, his chances of climbing something big were vanishing. Enock still wanted to attempt an objective that matched his dreams. Enock felt he had enough time to improve his systems, but he needed somebody to train with him, and felt that with the right team, he could climb an appropriate wall. I concurred and continued helping Enock train and put together a team psyched to bring him up something substantial

We spent our days training at the Laconte Boulder, riding the bus back and fourth from Camp4. Watching Enock navigate Yosemite efficiently in his wheelchair was inspiring. He learned the bus schedule, figured out how to most effectively carry equipment, and learned which trails were best suited for wheelchairs. Enock figured out how to live and train comfortably in the Valley from his wheelchair, and Yosemite had become his home away from home. During this time, my confidence in Enock increased. While his rope ascension still needed some tweaking, in my opinion this was manageable. His deficiencies were fixable and insignificant compared to the more pressing issue of amassing enough people to carry him to the base of the climb. To do this, we estimated we needed a team of at least 10 carriers. Without them, the climbing team was irrelevant.

We secured a climbing team that consisted of myself, Enock, Nick Sullens (a Yosemite Climbing Steward) and Christian Cattell (introduced to us by Timmy O’Neill). Although Enock and myself were the only two remaining from the original climbing team, and some people switched roles, everybody ended up exactly where they needed to be. The climb would not have been possible without carry teams, ground support, logistical help, gear assistance, and general support for Enock while living in the Valley. Each role was vital to the success of this undertaking. The climbing team made one final adjustment. We decided to bring Enock up “Astroman,” a well known free-climb, instead of the Prow. We would still plan on climbing wall-style, hauling gear, and allowing Enock to spend a night in a portaledge. This would allow Enock to learn the systems necessary for climbing El Cap while the rest of the team enjoyed world-class free climbing instead of aid climbing on the Prow.

The day before the climb, we shuttled gear up to the base of Astroman. Aware that this preparation was frivolous without a carry-team, we proceeded hoping for the best. While shuttling loads, I sent text-messages back and forth, trying desperately to round up a team. That evening, prior to going to bed, we still only had a 4 person carry-team, not nearly enough. In desperation, I made one last effort and walked around Camp4 at 10:00pm searching for volunteers. I sheepishly entered a campsite that happened to be hosting a party, and to my astonishment was able to round up five more people! I was elated but also concerned that after a night of festivities they wouldn’t actually wake up the next morning. To my relief, at 6:30 the following morning they were all there with the rest of the group at the Search and Rescue (SAR) site. In total there were about 15 helpers. Seeing all those strangers together drinking coffee, introducing themselves, laughing and in good spirits at the crack of dawn was truly inspiring.

The carry was well organized. We transported Enock safely in a litter through uneven, steep terrain. The quantity of helping hands made the carry both efficient and safe. We were able to rotate jobs from carrying, to spotting, and resting; and at no point did it feel as though anybody was lifting too much.

We beamed Enock through the most challenging terrain, passing him gently from one stance to the next, everybody scrambling to help where they could. It was inspirational to see this process unfold, a bunch of strangers working together as a team. Every so often, I glanced down at Enock lying peacefully on the litter with his arms crossed across his chest. The trust he had in the carry-team to get him safely to the base and the courage required to ask for that much help was admirable. We reached the base in less than two hours. Everybody cheered (actually mostly monkey noises) and we passed around a celebratory Cobra malt liquor before the carry team hiked down.

The carry was well organized. We transported Enock safely in a litter through steep, rocky terrain. The quantity of helping hands made the carry both efficient and safe. We were able to rotate jobs from carrying, to spotting, and resting; and at no point did it feel as though anybody was lifting too much. We beamed Enock through the most challenging terrain, passing him gently from one stance to the next, everybody scrambling to assist wherever was most helpful. I was inspired to see this process unfold, a group of strangers working together as a team. Every so often, I glanced down at Enock lying peacefully on the litter with his arms crossed on his chest. The trust he had in the carry-team and the courage he needed to accept that much help was admirable. We reached the base in two hours. Everybody cheered (actually mostly monkey noises) and we passed around a celebratory Cobra malt liquor before the carry team hiked down. The rest of us remained and prepared to climb. We packed the haul bags, Enock got prepared, and Nick racked-up and started leading the first pitch. Our strategy was to have a climber lead each pitch and use a thin tag line to shuttle up a static rope for Enock, the haul bags, and myself. The second climber then follow the leader and I jugged next to Enock. This allowed me to attend to Enock while also filming.

To climb, Enock uses an ascender altered with a pull-up bar for improved grip. Without the use of his legs, he relies solely on his upper body to essentially do pull-ups to ascend the rope. Vertical terrain is easiest for Enock as there is less friction between his body and the rock. As Enock started up the first pitch, I think we both felt relief. We had been dealing with so much uncertainty up until that morning, and in many ways it felt like we were beginning the easiest part of the trip. He was finally able to focus on climbing and forget about everything else. I asked him how he was feeling and he became very emotional. He expressed his gratitude for everybody who helped and was overwhelmed with joy. Tears streamed down his face as he began ascending the first pitch. That first day, we completed five pitches, ending at the top of the Enduro Corner on a ledge. We moved efficiently considering the heavy hauling and the fact that this was Enock’s first significant climb. That evening, Enock got to spend his first night in a portaledge.

The weather forecast showed a chance of thunderstorms the following evening. Considering the time and effort required to descend with haul bags and Enock (who cannot rappel and must be lowered) and also the hike out (which would be treacherous carrying Enock over wet, rocky terrain), we did not want to get caught in a storm. Additionally, at this point Enock had effectively practiced what he needed to prepare for a larger climb. He had efficiently climbed 6 pitches, spent a night on a portaledge, practiced transitions, and got a glimpse of what it would take to climb El Cap. Accordingly, we decided we would start heading down the following day.

Before going to Yosemite, Sean shared some advice with Enock. He told him to remember to look at the stars, advice that Lynn Hill had shared with Sean before his first wall climb. That evening, resting comfortably on our portaledge high above the Valley floor, we were treated to beautiful clear skies. Enock experienced the magic of sleeping in the vertical world, decompressing on his back from the exhausting work of wall climbing, and tracking the night sky sandwiched between the silhouettes of Halfdome and Washington Column. The following morning we took Enock up one more pitch, lowered down to the portaledges, packed up and prepared to descend. Due to our climb being cut short, we had not yet arranged a carryout team, so I hastily sent a text to our ground crew hoping they would be able to secure a team.

Our tactic for descending Atroman was to use two 70m ropes tied together to lower Enock all the way to the ground while Nick rappelled next to him. Then Christian and I each rappelled, with one haul bag each. After we made it down, Enock remained at the base while Nick, Christian and I began shuttling gear back down to the parking lot. When we arrived at the parking lot, we were relieved to be greeted by a carryout team of ten people! Once again, I was overwhelmed with gratitude and inspired by team rallying with such short notice. Many of the same folks from the carry-in team also helped hike out. Everybody in good spirits, we hiked back up to the base, strapped Enock safely into the litter and carried him out.

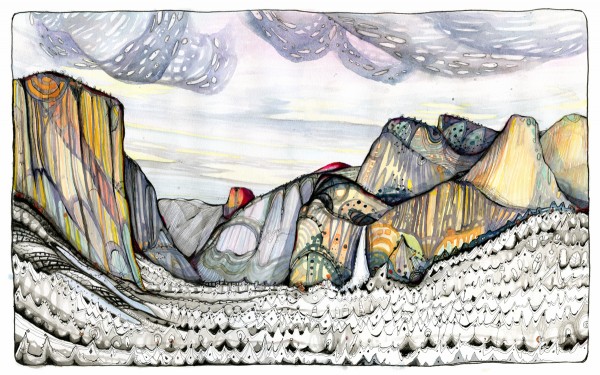

Enock flew home to Maine a couple days later. I helped him carry his luggage from Camp4 to the cafeteria where he caught the bus to the Fresno Airport. I watched him get hoisted into the bus by the automated handicap lift and waved goodbye. That afternoon I hiked up to Glacier Point to work on a photo time-lapse and some illustrations. While I was drawing I reflected on how this experience was so influential. This trip was quite different from previous ones I had made to the Valley. Typically I show up to Yosemite with my own climbing goals. I spend my time prepping for a couple significant climbs and I am focused on all the details required to make that happen. For this trip, however, I arrived without any lofty climbing objectives of my own. Instead, I spent most of my trip observing Enock’s transformation. I was inspired and honored to witness the process unfold. Enock camped in the Valley without a car, wheeled himself around on dirt and rocky trails, and relied on the bus system for almost a month - there was nothing efficient about this process yet he made it happen.

People travel from all over the world to climb in Yosemite, focused on very specific personal climbing objectives - rightly so as they invest large quantities of time and money to climb some of the best and largest granite features in the world. However, Enock fostered something truly special within the climbing community. People came out of the woodwork, compelled by something other than their own climbing objectives. Why did people help him? I suppose there were a variety of reasons. However, I speculate we all see ourselves reflected in Enock. His presence was a reminder that each and every one of us could be in a wheelchair, and that if that were the case, we would surely hope that the community would rally for us.

While Enock received a lot of generous help and support, in many ways everyone else benefitted even more. In my opinion, one of Enock’s greatest accomplishments was not the climbing, rather his uniting of the Yosemite community. I asked Enock what he thought of his experience and he told me “I didn’t climb exactly what I wanted but I got what I needed.” I think Enock got a lot more out of Yosemite than he bargained for, something more significant than climbing El Cap. He left with a greater understanding of both the Valley’s limitations and its allure. Enock showed up to Yosemite not even knowing what he did not know. He left with a new community and the experience to climb El Cap next year. What he shared with the Valley was equally as special: help is available if you want it.

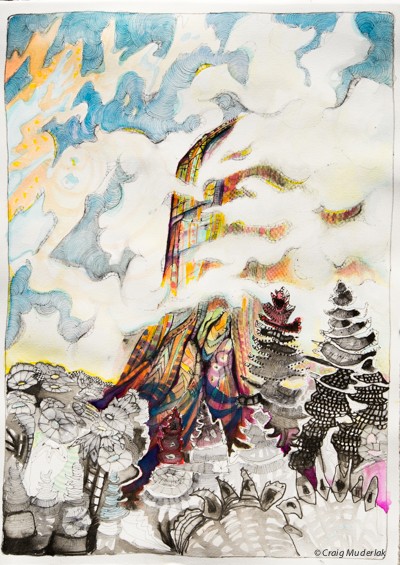

http://www.muderlakart.com

-the monkeys are sending!