Wanted to save this old article from We Alaskans an insert of the Anchorage Daily News in 1991 that interviewed climbers and the folks of Talkeetna. TR format seemed a good way to do it.

It serves a bit as a report of my first trip on Denali as an apprentice guide. There are errors in the Article. The date of the Earthquake was April 30th 1991 not 1992. In the party I was part of we did not tell clients to get out of the tents. Quite the opposite. I watched the avalanches from the tent door up to the last second before zipping up. I was not gonna miss any of it if it turned out to be my last minute on earth. As I watched the powder clouds from both sides of the glacier approach I realized they had slowed down enough by the time they reached us that no debris was going to hit us fortunately.

Major earthquakes have hit on Alaska mountains several times in recorded mountaineering history since the pioneer days.

Matt and Julie Culberson are interviewed in this article as is Gary Bocarde. It's a tiny piece of Alaska Mountain History that I hope you enjoy.

The night Denali shook

by Doug O’Harra

The earthquake began with a jolt, waking two men asleep in the bunkhouse of a lodge at the base of the Alaska Range. The motion continued, slower at first and then accelerating harder and harder.

Marty Bounds’ eyes locked with those of another worker at the Chelatna Lake Lodge.

Denali at Sunset by NPS

Denali at Sunset

National Park Service

“I think this is a bad one,” the other man blurted out.

Bounds, an Anchorage carpenter who’d traveled to the foothills south of Mt. McKinley to build a cedar chalet, thought to himself as the shaking worsened: This building is coming down.

Both men scrambled afoot and ran. As they sprinted past the kitchen, pots and pans clattered to the floor. The walls creaked. Guns tumbled free from a case. Keeping his balance, Bounds dashed barefoot out the front door into the chilly night of Alaska’s spring.

Only seconds earlier, some 70 miles straight down, four to 12 miles of basalt once part of the Pacific Ocean floor had suddenly slipped about four inches further into the earth’s mantle. The energy released equaled the explosion of the A-bomb over Hiroshima.

The primary shock — a compressional wave not unlike the report of a sledgehammer striking granite — had rocketed upward at about three miles per second, eventually registering 6.0 on the Richter scale. Secondary shocks — side-to-side waves — followed immediately and were also large: registering 6.6.

Bounds, standing at the epicenter of the largest earthquake ever recorded at that depth in southcentral Alaska, was struck dumb by what he saw.

“You could see the wave go across the ground,” he said later. “The spruce trees were going back and forth four to five feet. It looked like a 40 m.p.h. wind was blowing them.”

Then it subsided. It was nearly the middle of the night on April 30, 1992 — a date and time of day when the light still glows on the Alaska Range with a dim reddish tint.

Bounds and his friends, laughing and joking and relieved, finally stared up into the mountains before returning to bed. Mount Russell, visible over the head of the still-frozen lake, seemed untouched. Foraker and Hunter stood to northeast, blocking the view of Mt. Mckinley. Climbers trying for the summit would be camped out all over the glaciers between the two peaks.

Fifty miles east, in Talkeetna, the staging site for Alaska Range climbing, the quake had struck with the same force.

Jim Okonek, owner of K2 Aviation and one of the chief mountain pilots at the time, was sitting in his house watching TV when the shock wave began jiggling his home.

Things fell off the shelves, hanging lights swung, a basket of mementos plunged from the top of a rickety old dresser.

Okonek immediately called his daughter’s house in Anchorage, where his wife was visiting.

“I wanted to see if Anchorage was still there,” he said.

He worried about a Cessna 185 he’d left at the hanger on blocks.

“I expected to find it on the floor in the morning,” he said later, “but it turned out to be OK.”

Then he thought of the mountain. A sinking feeling.

“We had people up there,” he said. “It was bound to trigger avalanches.”

Only a few hundred yards across the village, Bob Seibert, the chief climbing ranger for Denali National Park, lay asleep in his bed when the quake hit. In his eighth year in Talkeetna, Seibert had felt many earthquakes before.

But this time, he and his wife, Susan, gaped at each other, waited for it to stop. They waited a little longer. Then … they just dashed for their children, ages 1 and 3, intending to hustle them out of the house.

“It was the first time for that,” Seibert would say later. “Usually you just wait it out.”

The motion stopped as they reached the kids, after 30 seconds or so. Seibert then rushed through his house, looking for cracks in the drywall.

The lights hanging from the open-beam ceiling were swinging impressively back and forth, but there was no apparent damage. Everything seemed secure, as though the earthquake had never happened at all.

“The very next thought was for all the people up there,” Seibert said. “It was just like: ‘Oh boy, I wonder what this did to the Range.’ It was obvious that it would have shaken certain things down.”

At that moment, Seibert and his staff had registered some 200 climbers. In all, fewer than 250 people were camped in the range, most of them on climbing routes for Foraker or the McKinley massif. When the quake struck, they could be anywhere. Some of them could be dead.

Top of story | Return to Cold Quests | Return to FNS

Nearly 100 miles south and east of the Chelatna Lake epicenter, outside Palmer, geophysicist Bob Hammond had gone to bed and was reading a report about California’s San Andreas Fault. At 11:18 p.m., his wife came running in and said she felt an earthquake. At the same moment, Hammond said, “I felt the P-wave arrive and kind of bang the house. I got up, to get my clothes on, and I felt the S-wave arrival.”

Hammond, a staff member at the Tsunami Warning Center, simply went straight to the center. In the hours following a major quake, the phones ring constantly. The chaos climaxes right as the seismologists and geophysicists are scrambling to make sure the quake hasn’t generated a tsunami that would threaten coastal areas.

But Hammond expected even more interest this time. During the previous two weeks, four other relatively large quakes had struck the Anchorage area. People were getting alarmed. One guy had called from a bar, convinced that Hammond just knew when the next “big one” was coming. But, as Hammond assured him over and over and over, “I can’t predict when the next big earthquake is going to happen. I just can’t do that.”

The forces that led to the quake beneath Chelatna Lake stem from the same broad processes that created the Alaska Range, the Cook Inlet and Aleutian volcanoes, and make southcentral Alaska one of the most earthquake prone areas in the world.

For millions of years, the North American continental plate has been riding over top of the North Pacific Continental plate, forcing it down into the earth. Though the forces involved are immense, the speed is inexorably slow: about as fast as fingernails grow.

“Back under Anchorage, the Pacific plate is moving northward at about 6 centimeters per year, about 2 1/2 inches, and the North American plate is being squeezed upward,” explained geophysicist John Davies.

The Pacific plate gradually gets deep and hotter, eventually peeling away from the North American plate as the force of gravity and the tremendous pressure thrusts it deeper and deeper into the hot mantle of the earth.

Under Mt. McKinley, the two plates have separated, with mantle between them. Thus, the Chalatna Lake quake didn’t change the mountain’s elevation. But the jolt of such a massive amount of material slipping deeper into the mantle toward oblivion was enough to rattle the entire McKinley massif.

Traveling at 3 to 4 miles per second, the tremors jiggled loose ice and snow from miles of slopes and cliffs and faces. Billions of tons of ice with the tensile strength of steel shook free. Slopes that had stood for decades collapsed. Clouds of pulverized crystal billowed across the Kahiltna Glacier like tsunamis from ice hell.

For one brief moment, the ocean of ice and snow covering Denali flowed like water.

On the Kahiltna Glacier, more than two verticle miles below the summit of Mt. McKinley, 19-year-old apprentice guide Derek Roland was lying half awake in his tent when the quake struck.

Anchorage born and raised, Roland pays his bills with odd jobs, but really wants to make a living as a alpine guide. When the shaking began, he was tucked in his sleeping bag, listening to his Walkman, on the first days of his first trip up the mountain.

“You knew it was an earthquake,” Roland said later. “It was shaking the whole tent. I thought: ‘My god, we’re going to be hit an avalanche.’”

Following the lead of the head guide, Scott Wollums, Roland began yelling at the clients to get up, pull on boots, grab wind shells, get outside.

On the surface of the glacier, in the faint dusky light, Roland stood transfixed at the sight above him to the north.

“You’re surrounded by all these peaks, big peaks,” he said, “and everything on all the mountains is peeling off.”

One face after another — the Kahiltna Dome, the west ridge of Mount Hunter, faces that lack names, ice cliffs that rise 2,000, 3,000 feet above the relatively flat glacier, all thundered down in explosive white clouds.

“It was just unbelievable,” Roland said.

Then Roland and the other remembered they had cached a radio at a higher camp.

Oh my god, Roland thought. There’s got to be a lot of people getting killed up there.

Visit on googleusercontent.com

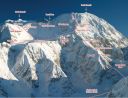

(Camp at bottom of ski hill where we got hit by 2 powder clouds from opposite sides of the glacier. not part of article)

A little ways off, 34-year-old Christoph Dietzfelbinder, an experienced mountaineer from Smithers, British Columbia, had camped with a climbing partner after spending three or four days preparing to climb Denali’s West Buttress.

He had selected his tent site for its safety, in what he calls a “compression zone” a location always free of crevasses.

Then the earthquake struck. The shaking began.

“I popped out of my tent immediately,” he said later. “You could hear the thunder of the avalanches all around.”

He was safe, he told himself. Avalanches can’t reach this spot. It’s too safe. But then again, he argued with himself, if there’s enough mass in an avalanche, it could travel for miles. It could travel down the glacier and reach this spot.

Such thoughts, and the sight of so many avalanches, finally rattled Dietzfelbinder.

“I was intensely scared,” he said. “It was extraordinarily scary to be in that situation. I don’t live in earthquake country, so I’m just not used to it.”

Top of story | Return to Cold Quests | Return to FNS

One thousand feet further up the Kahiltna Glacier — perhaps four miles north of Foraker and five air miles from the summit of McKinley — a 12-man expedition from Provo, Utah (called Utahans On Everest) lay asleep among six tents.

“We had located our camp in a pretty safe place,” said expedition leader Douglas Hansen. “We had probed for crevasses.”

Then the shaking struck. Hansen, half asleep in his sleeping bag, thought: “Hmmm. The glacier is shifting.”

Then Hansen heard the avalanches.

Outside on the glacier, Hansen and the members of his expedition stood in the cold dusk and watched agape as square miles of white plummeted to the glacier in colossal explosions of billowing clouds of ice.

“To the west, the whole side of it came off and literally crossed the valley and billowed up,” Hansen said. “They were on all sides of us. It was impressive.”

Those on the Kahiltna floor — a river of undulating ice cutting through the canyons of peaks — reported the same sequence of events.

“They saw ice falls start down and hit the glacier surface,” Seibert said. “Then it builds up and these large ice chunks are pulverized, and the pulverized ice chunks are swept up, and they billow up into huge clouds.”

Base camp manager Ann Lowry reported to Seibert that the massive avalanches further up the slopes gathered in force and hit the base camp with spindrift — clouds of pulverized crystal &151; and pounded them with high winds that lasted for a half hour.

People huddled in their tents wondering if they would be consumed by an avalanche.

On the Cassin Ridge, in a camp overlooking the Northeast Fork of the Kahiltna (called the Valley of Death for its avalanches,) guides Matt and Julie Culberson reported seeing avalanches thunder down each side.

In seconds, the avalanches overran the floor of the valley. When they met in the middle, the two sides rose upward, forming an eerie mushroom-shaped cloud of crystal.

“The west ridge of Hunter was coming across the valley floor like a ski jumper, like a tidal wave,” said climber Bill Mattison only a day later. “It just jumped over some little mountains and was coming right at us. There was nothing we could do.”

On the ridge directly above the avalanches off Hunter camped long-time climbing guide Gary Bocarde and a party of five others. For nearly a week, they had been battling poor weather in an attempt to climb Hunter by way of the technically demanding West Ridge.

By the time Bocarde and his party reached that portion of the ridge, they were exhausted, in need of a rest day, in need of a change in weather.

But even selecting tent site proved difficult. While probing the ridge, Bocarde knocked loose a portion of the cornice and fell 15 feet (his fall arrested by the rope.) They moved 10 feet further in. Then Bocarde uncovered a deep crack. They moved five feet further in from that.

By 9 p.m. or so, the group has bedded down. Bocarde and old friend Stewart Hutchinson lay in a tent only 15 feet from the sheer drop.

It was clear that several of the group felt, well, somewhat unsettled by the exposure, Bocarde said. Hutchinson — an experienced mountaineer who’s climbed K2 in the Himalayas — had expressed fear that the entire cornice would go, sweeping the tent, the camp, the whole ridge top, right off the lip for a thunderous, screaming free-fall plunge to the glacial floor.

Bocarde, mostly unfazed, simply went to sleep. Then the shaking began.

“What happened is I heard the tent doors unzipping. It was Steve, unzipping the doors, and I mean he was fast. He was flying out the door, yelling: ‘It’s going! It’s going!’”

Bocarde thought: “Whoa!” Maybe the cornice was going after all.

So Bocarde scrambled out in to the blowing wind and icy cold temperature of an exposed ridge, wearing only wool socks and long johns. All around them came the deafening sound of avalanches. It was as though the entire world out of sight had released into avalanches.

Of the other two tents, one was secured among small rock towers. Those guys, Bocarde said, stuck their heads out the door and then ducked back in. They weren’t worried.

But the other tent was only a few yards further up than Bocarde’s. And the mosquito netting zipper was stuck, and the climber inside kept jerking and pulling, jerking and pulling. Finally he dove right through the mosquito netting, but got stuck half way out.

Bocarde and Hutchison grabbed a hold of his arms and began trying to pull him the rest of the way out. When the shaking finally stopped, the two men were still trying to pull him out. A fourth climber was nervously stuck inside the tent.

The thunder kept going.

“We heard noises, like cracks,” Bocarde said. “Right below us, a lot of big ice faces were going…. It just sort of seemed so intense that I thought it might be the ridge right below us.”

Then the shaking and the noise subsided. What had happened? In the dim light and blowing wind, Bocarde and his partners could not see details of the surrounding slopes. And it was cold.

So the guide and his team, standing around in their wool socks and long underwear, finally just went back to their sleeping bags. As he snuggled down in his bag, Bocarde was struck by the absurdity of rushing out of the tent in underwear.

“I’m not sure what we thought we were going to do,” he said later. “If the tents would have gone, we would have been standing out there in booties and long johns. We would have just frozen to death.”

Top of story | Return to Cold Quests | Return to FNS

Over top of the summit, something like 12 miles to the north, camped a German couple on the Harper Glacier, near a section at the 14,000-foot elevation where the slope flattens a bit and offers a zone safe for camping.

Ralf Holland-Letz and Marinne Stolz had reached that spot after a nearly 20-day ski and climb from Kantishna up the Muldrow Glacier via the difficult Karstens Ridge.

“The summit wasn’t our main goal,” Letz said. “Our main goal was to do the traverse, and to do it on our own without flying in.”

Shuttling two loads up and down between high and low outposts on the route, the two climbers worked their way up the glacier, up the ridge, past the peak of Browne Tower and out onto the Harper, named for Walter Harper, the first human to stand on the summit of McKinley. They were, perhaps, only a few days away from reaching Denali Pass and the route down to the Kahiltna Glacier.

Out of the glacier, Letz found the remnant of a massive crevasse. It split the glacier like a trench, but was packed solid almost to the rim with a floor of hard snow.

The two climbers walked into it, they probed with poles. They studied it. Letz and Stolz decided that snow filled the crevasse from the bottom. “We thought it was completely safe,” he said.

So, after shuttling another load up, the two set up camp inside the protected trench made by the crevasse. On the uphill side, a 10-foot-high rim blocked the wind. On the lower side, a 4- to 5-foot wall overlooked the falling slope of the glacier and the sweeping expanse of the Muldrow and the plain below.

By nightfall on April 30, the couple had made a comfortable camp: fuel bottles and stove stashed neatly on ledge outside the tent, gear tucked inside, sleeping bags down. They went to sleep early.

They awoke when it hit.

“There was this incredible noise,” Letz said. “I thought it sounded like somebody shook steel cables together, and the shaking got harder. It brought us to our knees in the tent.”

The image of a massive avalanche thundering off the ridges on to the glacier crossed Letz’s mind. But he knew he’d camped far enough out on the glacier that he’d be safe. Then, without warning, the floor of the world fell.

“It was just like an elevator — swish!” he said. “It wasn’t a hard fall. It just dropped.”

In the sickening instant of horror that followed the drop, Letz thought sure the crevasse was closing over them. The tent was crumpled around them. He thought they would be trapped. But the shaking stopped. Their tent didn’t move again.

Letz unzipped and looked out. The fuel bottle that he’d stashed within arm’s reach was 15 feet above him.

The two dressed and crawled out of their ruined tent. They were stunned. In the half-light of dusk, they walked up the crevasse, discovering a new bottomless chasm yawning only 50 feet away.

They examined their tent: two poles had snapped, another bent pole had ripped open the fly. The tent was ruined beyond the reach of field repairs.

“We were just standing there, making our heads clear,” Letz said. “Continuing would have meant building snow caves. But then we decided we were quite lucky to survive that. So we wouldn’t push it further. We decided to go down as fast possible.”

Letz and Stolz scrambled through their things, loading their packs with high-energy food and clothes and a stove and a shovel — “just the necessary gear.”

They abandoned the tent and left weeks of supplies in the crevasse.

The descent commenced about 1 a.m. on May 1 beneath a dusky sky filled with the pale bars of aurora overhead. There was just enough light to see. The two climbers retraced their steps back across Harper Glacier, down beneath Browne Tower, out on to Karstens Ridge. It was, Letz said later, a terrifying journey.

Imagine the crunching crampons on new avalanche after new avalanche. The trail of old bootprints leading directly into fresh chasms. The safe, known route now twisting through one new hazard after another.

“At first we had just thought the glacier had moved, but then we realized that everywhere there were new crevasses, huge ones. Every gully there were avalanches.”

Picking their way down past the debris of pulverized ice and around the fresh blue ice of new crevasses, the two German climbers walked steadily without stopping all night, all day, all night and then into the next morning.

After 36 hours without stopping, they reached Kantishna, thankful to be alive.

Letz’s conclusion was simple: “We were lucky.”

In the wind-blown morning of May 1, up on the west ridge of Hunter, Bocarde and his friends rose to a clear morning.

“Just about every direction that we looked we saw evidence of something happening.”

The northeast face of Foraker looked swept clean. A massive avalanche had charged down Mount Crosson and extended at least a mile and a half into the Kahiltna’s flat surface.

Avalanches on every peak? Bocarde radioed Kahiltna Base Camp. Did we have an earthquake? he asked.

Yeah, came the reply. It was major.

Over the next few days, Bocarde and his group eventually were pinned down by blizzards and turned back without reaching the summit of Hunter. As they retraced their route down the West Ridge, they traversed a section known for colossal cornices, some 100 to 200 feet thick, that overhang a tremendous drop to the floor of the Kahiltna Glacier.

Over and over, Bocarde said, he found their foot prints leading straight into chasms, breaks where cornices decades old had plunged into the valley below.

Top of story | Return to Cold Quests | Return to FNS

The same morning found Dietzfelbinder and others camped on the lower Kahiltna, discovering their stable glacial table top had been ripped open. A new eight-foot-wide crevasse now cut right through the middle of their “safe” tent site. It was deep, hundreds of feet, its bottom lost in bluish darkness of glacial ice.

“It was,” Dietzfelbinder said, “quite unpleasant to see.”

Nearby, apprentice guide Derek Roland awoke eager to climb. The quake hadn’t dampened his enthusiasm at all.

“It’s something I know was possible on the trip,” he said. “Even before the trip, I had thought about earthquakes. But the mountains are too incredible. They’re worth it.”

But Hansen, the seasoned Utah trip leader camped several miles further up the glacier, took a slightly different lesson.

“When you’re young, you may have a concept of life and death and mortality, but you don’t have a concept of your own mortality,” he said. “When I was starting to climb, the danger didn’t impress me very much. When you’re young, you almost convince yourself that you won’t die.”

The massive failure of the ice on the slopes reminded Hansen and others of the closeness of death on the mountain.

“It kind of woke us up,” he said. “It reminds you that yes, you are in a natural environment and yes things can happen. Sometimes you think that you’re in a static environment, but things can happen and you can end up dead tomorrow.”

Hansen, used to the notion of calculated risk, put the earthquake behind him. It was a tap on the shoulder, a reminder. But others in his group could not.

On a training climb for a 1992 assault on Everest, Hansen found that many of his climbers never felt the same about the trip after watching every face in sight explode into avalanches.

“Ultimately it hurt our expedition,” he said. “Part of our route was up the Northeast Fork, the Valley of Death, and some guys were really concerned about being caught in the middle.”

It turned out that individuals in the group had lost their nerve, and were unable to climb the West Rib, one of the popular technical routes on Denali’s west side.

“It was just a little more scary, and they were a little more inhibited,” he said. “They may have made it up the Rib if those avalanches hadn’t happened.”

All over the mountain, faces had changed. Jim Okonek of K2 Aviation flew around the mountain and discovered the colossal Wickersham Wall — a 14,000-foot drop off McKinley’s North Peak to Peters Glacier — totally altered by avalanches.

Harper Icefall, once sculpted with tiers of shingled ice curtains, had become “as smooth as a logging chute,” Okonek said.

Yet, for all the destruction, for all the avalanches, no one reported any injuries. No one died. Seibert called it a “miracle” that it came at night when everyone was bedded down. That it came in April and not June, when everyone climbs all night in the perpetual light.

“Providence is a good thing,” is how Okonek put it.

In the days that followed, two notions arose among climbers. One group &emp; mainly people from Outside, away from Alaska — thought the quake would have made the mountain safer than it had ever been. After a shake like that, the reasoning went, nothing will fall now.

But Alaskan guides and climbers tended to take a different view. A shake like that, they said, is bound to have cracked something else. It’s now more dangerous than ever.

Seibert, the ranger, said he agreed with the Alaskans. Otherwise, he said, “You would be lulling yourself into a false sense of security.”

END ARTICLE

---------

Visit on googleusercontent.com

Pretty Hardcorp introduction to the big mountains but I was hooked. My trip ended by taking a client who felt over his head back to Talkeetna. I was back on the Mountain for a 28 day ski trip in less than 2 months.