Trip date August/September 2015

Background- Honduran Moskitia (specifically the Rio Platano Region) is considered to be the largest intact rainforest left in Central America. The surrounding tributaries are largely unexplored and no Indians inhabit the mountainess regions. Due to the remoteness and lack of government presence, drug cartels and illegal logging is rapidly encroaching into this area. As of date there are still large areas unaffected/unexplored by people for 500-1000 years. I have made two previous trips traversing from the headwaters of the Rio Platano to the Caribbean by raft.

This trip was to walk deep into the heart of the Rio Platano and explore remote valleys/tributaries that haven’t been seen in a long time.

The team consisted of my two friends and me-

-Micho (Moskitia Indian and master of the jungle)

-Jose (toughest Honduran I have met, and hell of a woodsman)

-Me (your typical hillbilly from Kentucky)

Figure 1 Moskitia Indians in canal connecting Ibans Lagoon and Rio Platano

We heard rumors of a poacher route from the Rio Paulaya valley that would save us time accessing the remote regions of the Rio Platano we were interested in. So we loaded up the pickup, drove 9 hours and headed to the end of the road where a tributary named Rio Tulito flows into the Rio Paulaya.

Figure 2 Ferry across Rio Sico. Note the old trestles from former USA banana companies (abandoned 1960's).

En route while trying to decide which muddy two-track goes vaguely near Tulito we flagged a guy down in a nearby pasture. He walked up leaned in the truck pointed to me and said, “I know you. I saw you in March on the Platano”. He was one of many friendly Hondurans that helped immensely for no gain of there own.

We continued on with a new sense of direction, we had been on the wrong “road” headed to Olancho/Catacamas!

To be fair about Honduran hospitality, we had three guys in Las Champas walk beside the truck to the Rio Paulaya to show us where we could drive across. We pulled up to the edge of the gravel bar, and I immediately thought these guys are f---ing with us. It was about 40 yards across, looked deep and very strong current. All I could see on the far bank was cattle trails. Another local showed up shouting about something. He had seen us pass and noticed the back license plate on our truck was falling off. He brought string and tied it back on. I took my wallet etc… out of my pants and started to wade into the river to check depths. A cowboy serendipitously appeared on the far side pushing 30 head of cattle. The cows had to swim and the current sent them downriver a good distance before they reached our side. That definitely confirmed my suspicion.

I knew we couldn’t trust the three guys that led us here, but the license plate fellow whistled to a house and a guy ran out and started his motorcycle. He waved us backwards and led us through a maze of two tracks for 15 minutes. Once the road was obvious he stopped and hollered “buena suerte!” (good luck).

It was dusk and we were now going through wire gates and simply driving pastures looking for gates or any house so we could ask permission to camp. We pulled up to a beautiful ranch above the Rio Paulaya. The wife invited us in, gave us a great meal, and said her husband should be home shortly. Crelios is the rancher’s name. He arrived at nine PM and seemed excited to have visitors and to talk about adventures in the jungle. He lent us his number one cowboy and a mule to help carry gear the initial 16 miles into the woods. He would not allow us to pay for the meals, or beds.

I started setting my hammock up between citrus trees in the yard. Several folks ran out and said they are putting new sheets on a bed for me. Crelios had his family straighten up their bedrooms and made us sleep there. The family set up hammocks on the porch.

Everyone seemed interested in me. Micho told them I eat snakes and study fireflies (folks don’t know how to respond to that). The residents also stated they had never seen a gringo in this area. Most residents of Tolito had gathered at the ranch house to see the visitors that showed up.

Figure 3 Boa Constrictor not using his muscle but wanting to bite.

Unannounced, I went out catching fireflies in the yard. All eyes were on me. The whole village of Tolito was watching. Kids and adults were still trying to make sense of this gringo. I think initially they were wondering if I was still scoping out a hammock spot. I caught a couple fireflies and was suddenly surrounded by young kids asking why I was jumping around and diving at the ground. I held up a vial with a still glowing firefly. Some giggled, some spouted rapid questions in Spanish I didn’t understand, but all were running jumping and diving for bugs! We had a great time. The kids’ fear/suspicion of the first gringo they had met subsided. I had an enthusiastic entourage (adults and children) every step I took the rest of the night. I just wish my Spanish was better to help field the questions.

Figure 4 Firefly species (Photuris) giving distress flashes, in long exposure, as I tried and hold the camera and my arm steady for thirty seconds.

We left early carrying only light daypacks and Crelios’s cowboy leading a mule with the rest of our provisions. 5 miles into the hike the cowboy let us know he had never been to the Rio Platano and had no idea of the trail and route. We assured him it couldn’t be that bad and no worries. We didn’t know the trail either but are familiar with a lot of the territory.

Ten minutes into the hike we reached the Rio Paulaya. Micho flooded dugout crossing paulaya….

At the last house in the Tolito drainage, a man holding a rifle on horseback suspiciously watched as I snaked up the path to his house. I hollered “holla” and got no response, just a twitchy blank stare. (Probably should have let my Honduran buddies catch up before the approach). But he was acting like a dog that was all bark and no fight. The mood calmed down immediately when he saw our cowboy from Tolito. Herdo is the fellow’s name, probably the number one poacher in the Platano area.

A long conversation ensued. Our cowboy was trying to convince Herdo to join, because he was concerned about the route and traveling alone on the trip out. After 1 hour of talk, Herdo saddled a mule, packed a few items and we continued south. You could see hesitation in Herdo from the start.

Figure 5 Herdo preparing for an impromptu journey to the Rio Platano

30 minutes from Herdo’s house I filled my water bottle in a creek. He told me the water was bad, because of a large rotten “barba” (fer-de-lance) in the creek. I refilled from a nearby tributary.

The jungle had begun, no more slash and burn just virgin rainforest. We ascended a mountain and halfway to the top, without saying anything, Herdo turned around and went somewhere. Home?

I had been photographing a frog for my herpetologist brother when this occurred. When I asked, “where’s Herdo”, Micho said he was in front of us. I wasn’t concerned but unsure about Micho’s tracking abilities. The only fresh tracks I was seeing in front were White-Lipped Peccary, occasional Ocelot and week old horse tracks.

Figure 6, Smilesca species, upper Tolito River.

6 hours later I asked Micho, “You think Herdo is still in front of us?” He then admitted what I knew that he had turned back a long time ago. I am not sure if Micho was worried I would be worried, or the all too common “lost in translation” excuse?

The trail wasn’t terrible by Honduran standards (if that means anything to you). Periods of knee-deep mud straight up and down, with no visible cartological route reasoning. The trails are old/abandoned Pech Indian routes, centuries old that poachers have recently discovered. It is easy to look at the map and decide to shortcut certain geologic features, but completely different outcome whenever we tried it. There is a reason the route follows the route! I would use the term “trail” very loosely.

Figure 7 Ocelot by TMF

It was 16 miles as the crow flies, but we weren’t following any crows. It took us 3 hours to piece together one portion that led from the Camalotal river. Our poacher beta said it crossed the river a few times. What they meant was it crossed the river 7 times and on the eighth crossing you swim/walk downriver 1.5 miles then ascend a gully and climb 500 vertical feet to a ridge follow it due south and drop 600 vertical feet to an unnamed trib. We figured it out but it was very dark by the time we reached the Rio Platano.

Figure 8 Scratching heads and wondering how to get the horses down some rapids along Camolotal River. Just swim the ponies!¬

Two of Herdo’s hunting dog’s stayed with us. They were skinny hound/mutt mixes. Amazing to watch how quiet they were and would follow behind then veer off to check out a scent. Then fall back in line if the track was a bit cold. They are silent unless on a very hot scent.

On a Rio Camalotal gravel bar, while we spread out trying to find the “trail”, the dogs started going nuts and had something bayed. We all ran towards them and saw the “Tamandua standoff”. It was in a thicket beside the river, and I was battling to make my broken camera work and take pictures. The male dog suddenly jumped on the anteater and it wrapped onto the dog’s neck/head in a bear hug. The dog was thrashing around trying to shake it off, but the Tamandua had its 3 inch claws sunk into the dog. The cowboy jumped off trying to separate the two. It was such a ruckus he was hitting both dog and anteater with the flat side of his machete. The tamandua eventually let go and fell belly up to the ground. The cowboy stepped on its belly while trying to keep the dogs off.

Figure 9 DON'T STEP ON ANTEATERS BELLIES!

My newly attained wisdom on stomping anteaters… DO NOT EVER DO THAT, doesn’t end well! It latched onto his lower leg and foot and pierced his calf and ankle through his boots. Both dog and cowboy had big puncture wounds but our Cowboy just said, “todo macanudo- its all good”.

Our cowboy, the mule driver, was a great sport about all the difficulties. He never threatened to turn around and was a lot of fun to chat with and in great spirits. He hollered adios at 4 am as he headed home. I feel bad because my goodbye was so lazy I didn’t crawl out of my hammock. Just a hand through my mosquito net and “adios”. I have never been much of a talker at 4 am.

In the morning, we sorted gear and repacked, then jumped in the river to spear fish for meals. Even the old Pech Indian trails end at this point. We poured over maps again to ascertain our exact position and plan of route. Initially we crossed the Platano and hacked downriver. It was slow going. Micho and I finally agreed that we should just jump in the river. We swam 1 mile down the Rio Platano and ascended an unnamed tributary to the south. From this tributary we worked up to the headwaters and crossed a mountain range and dropped into some more unnamed tribs feeding the upper Rio Chilmeca. The travel was fairly easy but had to negotiate some cascades, waterfalls, two screwed up compasses, lost compass and other natural obstacles. Great start!

Figure 10 Our fishing gear and our catch... Wapote, Catfish, Slipper, Machin, freshwater crab and a sucker species. Note armadillo feet for bait.

I was still following Micho’s navigational orders for the first half of the day. I voiced thoughts and concerns but he was confident, so I followed. A few hours before dark with frustration on both sides, I realized his GPS compass leading him was screwed up. In a nice way I stated that in Kentucky and everywhere else I have been “the sun sets in the west”. That made sense to a Moskitia Indian. He said a long “Si”, and for the rest of the trip I navigated and questioned or vetoed any route decision he made.

I said, “lets drop south off this ridge and camp at the first water we see. It will be the same tributary we are trying to reach, just a bit upstream of the plan”. We did and reached and made camp 30 minutes before dark. I was extremely frustrated of lost/broken compasses and “GPS navigational dependency” skills.

Figure 11 Micho figuring on routes while I boil Supa palm nuts. We were all wondering how to get out of here at this point.

Late that night, while I was scrutinizing topos, I calmed down and admitted to myself we had to change route plans. We still had time to do the original route, but it would be a race to get out of the jungle not into. I stayed up late looking at maps trying to reconfigure our itinerary/route. My wife would whoop my ass if I was one day late out of here. That was looking very possible.

The reason I came here was not to just hike but explore and have time to really learn some areas. As I wrote this in my journal, a large herd of white-lipped peccary stampeded next to camp. They also spooked a Tapir that crashed into a bunch of trees and woke up a roosting flock of Mealy Parrots, and Macaws. Major jungle noises ensued. As the aforementioned crashed and squawked, kinkajous joined into the chorus. It took 2 hours for the kinkajous to settle down. Happy and tired I realized we had just crossed into an area that doesn’t see people. I walked the ridgeline the next morning curious if we had spooked the peccary or if it was a jaguar hunt. Inconclusive findings.

We cut overland (away from waterways) and I couldn’t convince Micho that the small contour wiggles on our crappy large-scale map are much more difficult than they appear. Our shortcut was not saving time but did provide dinner. I gave a slight whistle to get Micho and Jose’s attention. They stopped and I pointed out two armadillos 50 yards ahead feeding on a ridge across a creek. Micho turned to me and whispered, “I will kill them”. I gave a thumbs up and we hatched a silent plan. Micho took left, Jose right, and I got the middle. One armadillo fed down the ridge to Micho, he whacked/grabbed it as it crossed the creek. Dinner!

Figure 12 Nine-banded Armadillo skinning/butchering

We traveled overland for 1.5 days slowly working our way up the Chilmeca drainage and made camp where Rio Chilmeca and Rio Chilmeca run together (no typo on river names).

This valley was also untouched. I have been many places but finally found one that I have confidence doesn’t even see Pech Indians on a yearly basis. On the middle reaches of Rio Chilmeca we found one small Pech cuyamel fishing camp that we estimated was last used three years ago. A few days upriver, no sign of modern people activity.

In these southern valleys, I couldn’t sleep past 5 AM because of the cacophony of Mealy Parrots, Great Green and Scarlet Macaws. Night wasn’t much different. Tapirs whistled and herds of White-lipped Peccary stampeded and crashed all around. This only upset the Kinkajous, I loved the noise!

Figure 13 Great Green Macaws (Buffon's Macaw) their last stronghold appears to be Honduran Moskitia.

After exploring for 8 hours and 5 miles up a tributary and very tired and hungry I turned back towards camp. Both Micho and I had lost track of Jose who was carrying our meager lunch. Walking was tough (just following streams and side jaunts up mountains). Backtrack… Micho and I were working upstream but not following each other. I had found Micho 3 hours previous contemplating the map on a rock in the middle of the river. We both agreed to meet at the next trib (on the map) coming into the left descending bank. The travel got increasingly difficult and I was determined to not miss the tributary so I walked up the creek. I walked a long ways and saw many tribs entering the correct side but they were not on the map.

An 8 foot indigo snake spooked off a sandbar. The trail it left was a complete 4 ft circle in the sand. If I had not seen the snake I would still be scratching my head about the tracks. It looked like someone had drawn a circle with a walking stick in the sand. I love tracking stuff, new one for me.

I wanted to turn around but worried about Micho waiting at the tributary all night. I marched forward and found it! No Micho and I was confident he was behind me. I built a cairn on a boulder mid channel and added a cliff bar wrapper inside-out so the silver was exposed. Then I built a stick arrow pointing downstream.

One hour scrambling downriver I noticed a rock mid-channel that looked out of place. In wet finger pinched sand is said “Back Rive”. Knowing Micho and his struggles with English, I was relieved he had turned around and wasn’t hacking south looking for me.

Figure 14 Vine snake species

Shortly after a troop of spider monkeys started giving me hell. I have never seen monkeys act this way in Central America. Two individuals climbed down to eye level and started throwing sticks at me. I was tired but still wanted to mess with them. I started throwing sticks back and shaking branches. They went crazy, hollering shaking trees and throwing sticks back! These monkeys have never seen a person and saw me as another monkey. Maybe I am?

For 40 minutes I periodically saw wet footprints on rocks (Micho’s). A bit farther downriver no sign but assumed he was still ahead just not in the river. I got to camp and Jose greeted me with our overdue lunch and some fried fish we had speared the night before. He immediately asked, “where’s Micho?”. It was nearly dark and a large storm was threatening. As I ate “lunch” I could see major concern in Jose. I was running scenarios through my head on what to do if the worst did happen here and now. In my limited Spanish I tried to reassure him. I then got the satellite phone and sat on a rock midriver (where you can get service) and decided to wait till one hour past true dark before I called his brother (Berto) to let him know of the situation. I wasn’t worried but was becoming so because of Jose’s very apparent concern. I was dreading a nighttime search and rescue in unknown territory and rough walking, and wrestling with the best approach to initiate one, while still keeping myself and Jose safe.

Micho arrived just as the first fireflies were waking up! He had been distracted and examining some archeological site he stumbled upon. He had stories and smiles from ear to ear and pieces of pottery. I hate drama not instigated by me!

I need to be a bit vague on some of the locales considering the archeological sites we came across. Certain tributaries of many of the rivers we traveled would have huge sites of stone carvings and massive stone single piece tripod tables (250-300 lbs). Lots of pottery, large mounds and huge areas we called “graveyards”.

Figure 15 Large 250 pound metate/throne?. Tripod legs and cut from a single piece of stone.

The ongoing mystery is who were these people? Scholars don’t think Mayan. Locals including the Pech Indians say they were their ancestors but lack any information about anything. Whoever they were, built earthen/stone structures similar to Aztecs, and Mayans but these guys did come from South America. We could tell by certain trees you could find around sites. Supa Palms (South American/Panamanian species Astrocaryum standleyanum?) always foretold of a lot of stonework. And thank you for the Supa! We ate supa nuts as our lunch and dinner for most days we were there. Trying to harvest them is another story, probably the most danger we were ever in. Supa is the Pech name for this palm, not sure the exact species.

Another indicator of archeological sites is, Cocoa trees (non-native), and another species Micho and Jose were perplexed by. It fruited off the trunk like Cocoa, and had leaves that looked like Coffee trees. Micho’s random thoughts- may be a plant the Pech Indians call Chilmeca (maybe that is why this drainage got that name? Or maybe it is another South American sp. that these guys brought up?) Just Pech Indian hearsay of a small tree that is only found around archeological sites. Whatever it is we only saw it in areas we called “graveyards”. I have pictures of fruit, flowers, and leaves.

From the upper Chilmeca we need to head north (downstream). We built a balsa raft of 5 logs each 7 machetes in length. The first 4 kilometers was mellow water with class 1+ rapids and we made great time. The valley started to narrow, and we were pushing our luck on class III rapids before long. We pinned the raft many times and had to re-lash logs with fresh bark or vines. Downriver was getting much and much worse. I jumped out while Micho and Jose worked on the raft and scouted 200 yards below. Big class V-ish water. I whistled waved and hollered. Finally Micho sees me and I give an X with raised hands then ran my hand across my throat. Micho gives a holler, big thumbs up and jumps onto our log raft! Luckily he pins it quick the logs fly apart and we are chasing our packs down river.

Figure 16 Lower Rio Chilmeca. Note my friends and our balsa log raft upstream

Figure 17 Remains of our raft

Everything is gathered all is ok! As we admire the increasing size of the rapids we venture around a corner and see a “black hole” slot canyon the whole river funnels into. The walls are 80 ft overhanging with an additional near vertical 200 feet of veg and trees creating what looks like a cave. After 4 hours of trying to climb a weakness in the wall (kept getting cliffed out) Jose jumps into the entrance rapid and disappears around the bend and into the dark. I slowly scrambled back upriver to gain a vantage and waited. After 20 minutes Jose is clawing his way along the walls into sight. The roar of the river and contrasting light takes us awhile to figure out the correct hand signals. Finally we simplify from yelling English, while he is yelling back in Moskitia, “thumbs up”!

Figure 18 Jose et al. trying to figure out how to deal with the "black hole"

Jose is swimming in a small eddy clinging to the overhanging walls and was able to wrangle our packs as we tossed them in.

The “black hole” ended up being pretty safe. It was only 300 yards long but had good avenues to crawl onto boulders between the big rapids. We had given up keeping anything dry and just floated our packs and swam alongside. The darkness and unknown is what made us spend so much time scratching our heads.

We reached the Rio Platano again and swam downriver to the Rio Zorillo. From here we decided to follow the Rio Zorrillo all the way to the headwaters and divide with the Paulaya drainage. An amazing drainage, and lots of wildlife.

Figure 19 Sunbittern (I had dreamed of getting this shot!)

The Rio Zorillo is a medium sized drainage that’s headwaters are more or less due north of its mouth. It has a steady/high gradient but enough room to easily maneuver while route-finding and bypassing cascades etc. We crossed the Zorillo approximately 90 times and spent two days to reach the divide with the Rio Cuyamel.

Figure 20 Largest Ceiba tree any of us have ever seen. A true monster! Micho is sitting on a buttress 10-12 feet from the trunk.

Micho insisted on taking his boots off to drain water after every crossing. I used this time to keep working upriver walking slow and quiet.

I followed very fresh tracks from a herd of white-lipped peccary, and then noticed jaguar tracks on top of the peccaries’. Two minutes later 50 peccary were 15 yards in front of me. I know the jaguar was watching and saying, “really, god damn gringo here screwing up my hunt”. We briefly whispered a plan while drawing our machetes to attempt a hunt. They never spooked, were aware of us, but kept a distance of 25 yards and moved up a steep thick ridge ahead.

We kept moving at a steady pace and covered a lot of ground. We had planned on having 6 days to get out and we were all concerned if that was enough. We had no clue what terrain lay ahead. Days earlier it had taken us 8 hours to cover 1 mile. We needed to average 4 miles a day to make it out in time.

While working our way upriver, Micho picks up a skull below a very large buttressed tree. I see it as he reaches down. He asked, “is this a monkey?” My mouth fell open and said “hell no, that is a two-toed sloth skull”. As he picks it up all the teeth fall out. I start describing the osteological identifications that differentiate 3-toed, and 2-toed sloths. Micho listened obviously not understanding me then he joked that this guy, “fell so hard that it knocked all his teeth out”. I replied that this is most likely a Harpy Eagle feeding perch. We later found hair and bones all around the base of the tree, no nest.

Micho began to slow down noticeably. I was walking ahead and would wait whenever I thought I was getting too far apart. I would ask Micho, “Are you getting tired?” His response was always a simple “no”. It is hard to get an Indian to admit he is worn out.

Jose walked up holding a large terrestrial turtle. I took some pictures for identification purposes while Jose asked if we can eat it for dinner? He was a very old turtle that looked to have been chewed on by a Jaguar a time or two. I told Jose he reminds me too much of my pet tortoise “Redman” back home. We let him go. Unknown to me, that exact day back in Tennessee my 40-year-old tortoise had learned to use our doggy-door and had escaped. My buddy Redman is now doomed as winter approaches but his Honduran brother was saved from the pot. The coincidence is uncanny. Glad I didn’t eat his Rio Zorrillo friend.

I reached a beautiful spot with a crystal clear tributary flowing into Rio Zorillo and waited again. Micho caught back up, and I said, “lets camp here”. Micho wanted to assure me he could keep going, I said, “no worries this looks like a great spot for camp. I want to camp here” As we worked to start a fire and set up camp Micho said, “this is the hardest jungle trip I have ever been on”. The only time he let me know he was tired.

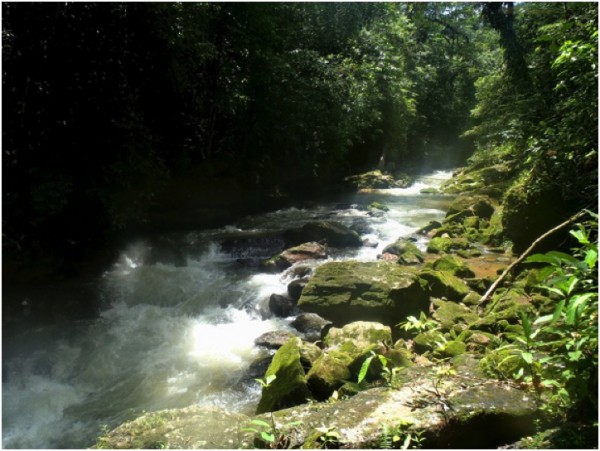

Figure 21 typical river scene in this region

We started cooking and boiling supa nuts. A deep rumble from a prop plane flying low drowned out the river’s roar. As Micho and Jose debated in Moskitia, I realized this was the only plane we had heard since entering the jungle. Micho was mumbling that the only scheduled flights that cross this area go to Puerto Lempira, his hometown. The daily flights don’t run at this late hour. They concluded it was either drug runners or Honduran military. Micho held his gaze upwards long after the plane’s rumble had faded. I could see concern and a twinge of anger in his face. I never asked him his thoughts.

That night an amazing firefly species gave one heck of a light show. They would glow orange while flying for ten seconds. The bugs then gave an extremely bright burst of light and went dark. Watching these orange trails glide through the jungle and the amazing flash at the end made me wish I had Grandmother and Pappy there. I laid back in my hammock and fell asleep to the Honduran version of the Elkmont light show.

We continued north the following morning. Micho was still tired but wouldn’t admit it. I got a bit ahead and sat and waited. A covey of Black-eared Wood-quail picked at bugs and leaves all around me. After 20 minutes I gave a whistle and heard Micho and Jose respond down the ridge. Another 20 minutes went by and I was wondering if I needed to walk back and check on them. I whistled again, they responded from the same area. I sat back and took in the beautiful surroundings. Looking to my left, I noticed a piece of stone 50 yards away. It seemed out of place/looked funny. I took my pack off and climbed down the ridge to look around.

It was over 150 tripod stone tables/metates from 5 inches in length to 4 feet (weighing up to 300 pounds). Most were plain amazing works carved from single pieces of stone. A few had intricate carvings on the legs and edges. One 60 pounder had legs like an animal and a head and tail (jaguar?).

Figure 22 Small metate at an archeological site that has ~150 pieces on the surface.

My left foot’s skin gave out immediately after this. I joked it is from the “curse of the Pech” for touching their or whoever’s stone sculptures. Or maybe 10 days of wet feet, god only knows. I was the slow one from here on out!

Figure 23 My feet were about done. You should see the bottoms of them. I always find it difficult to walk when the skin has been removed from the underside of my toes.

The Rio Zorrillo was now just a small creek. We continued up, and saw light, and entered a massive recent slash-burn. A lightly used trail appeared. I estimated 600 acres covering the entire upper reaches of the drainage. I couldn’t make sense of the cut. Huge mahogany and other very valuable species felled but left to rot. No timber appeared to have been removed.

We all were scratching our heads about it. The theories we came up with, in no order.

-Narcos (Drug Cartels), clear land to launder money as though it is a big agricultural operation

-Honduran settlers, simply clearing land for cattle and crops

-Archeological Site, clearing and burning to make the finding/looting easier

-Pech Indians trying to escape town and live isolated.

Regardless, it ain’t fun to walk through a recent slash burn. It is hot, no shade and countless massive trees you have to crawl over. Much of the grass is very coarse and slices you up a bit.

We found the logging camp. No one was home, and we stuffed our pockets with bananas hanging in the cooking area. I picked a few peppers to add flavor to our rice and Supa nuts.

Figure 24 Logging camp upper Rio Zorrillo. Getting snacks (Bananas and Peppers)

Near the Rio Zorrillo/Rio Cuyamel divide we entered forest again. We crossed over and made camp at the first place we could get water. At 600 meters elevation the tree species composition was different. Sweetgums all around! I was excited to find new fireflies for mom, but as dusk approached, nothing. At dark, still nothing. I laid in my hammock writing notes and never saw one flash!

We had planned on staying two nights at “divide camp”. After not seeing any firefly activity, and slowly admitting to myself that we are out of the virgin jungle, we packed camp, and kept moving.

A guy named Julio, was jogging up the trail (2nd person we had seen in 10 days) carrying only a small sack, rifle and machete. He was heading to the Rio Platano to spear a dozen Cuyamel (Sea-run Mullet/fish species). Julio is young (mid 20’s) and goes by the name “king of the jungle”. From our brief encounter, I would agree. We talked about various places he hunts and fishes. I mentioned human tracks I saw in the lower Chilmeca that looked several days old. He said, “that was me 5 days ago, but the gorge upstream is too dangerous to continue”. He said he has never been to the valleys above and doesn’t know anyone who has. We never mentioned we were just in those valleys.

I really liked this guy he seemed genuine. He was complaining about how his buddies always slowed him down. All he wants to do is travel fast and explore (that’s why he was alone) and shoot some Cuyamel to make money for the excursion. Julio let us know that the entire Rio Cuyamel drainage was now slash burn/ homesteaders. Looking for a silver lining, I told Micho, “if we can find a mule (for our packs) at a decent price lets get it, I don’t want to camp in cow pastures”. The look on Micho and Jose’s faces said, “thankgod”!

Six hours later we came across a house with people! The wife made us fresh coffee and we chatted for two hours about anything you can think. We finally got down to negotiating a price. Boss/Husband said “just give candy for my kids”. A Honduran saying while not sure on the negotiating, and wanting to simply help. I handed him 500 lempiras ($25 USD). Deal done, he threw in an extra mule and muleteer for the trip.

Figure 25 Our Rio Cuyamel Mule-skinner family we hired. Great friendly folks.

Four hours later traveling very fast we had dropped an amazing amount of elevation and reached the flood plains of the Rio Paulaya. Our muleteers (9 year old boy, and teenager) showed us the shallowest ford to cross, and vaguely told us how to get to Las Champas. We shook hands and I handed them 200 extra lempiras.

We swam, waded the Rio Paulaya. I was seriously hobbling down muddy dirt roads in the dark and pouring rain near Las Champas. My muscles felt great but my feet were now completely shot. We were asking anyone we walked past if they had beds. A simple “no” is all we got.

A Toyota pickup pulled up beside us and I heard a big laugh. It was Crelios, the rancher from Tolito!!! From 2 hours west, was in town buying some cinderblocks.

We helped load 2000 pounds of blocks into the pickup’s bed.

Crelios said, “if you ride with me back to the ranch, free beds, meals and a ride to Tocoa (6 hours away) in the morning. I just want to hear about the trip!”

I gave a thumbs up and jumped/hobbled into the bed of his truck.

Sitting on the back of an overly loaded pickup in pouring rain I relaxed. I was cold for the first time but thankful to be off my feet.

We reached the ranch and were surrounded by Crelios’s cowboys and workers. This ranch serves as a remote trading post of sorts. While unloading gear, folks kept asking if I needed anything. I said a Coke-Cola would be awesome. The wife heard me and apologized for only having Pepsi. She wouldn’t let me pay for it even though it came from their store.

All the Hondurans seemed excited to hear about the jungle. They live next to it but don’t venture in. Many workers asked if I need help on my farms in Tennessee.

Hours later while trading stories and chit chatting with cowboys a guy on a motorcycle pulled up and hands me a coke! He said he heard me asking for one, and had drove to Copen (3 hour round trip) to buy me one. I felt horrible. He wouldn’t take any money from me. We both had a coke while we tried to converse and we laughed about my crappy Spanish. Good people, good territory, and a lifetime of wandering and wondering awaits!

Figure 26 Jose (left) Micho (right). Enjoying a free ride to Tocoa

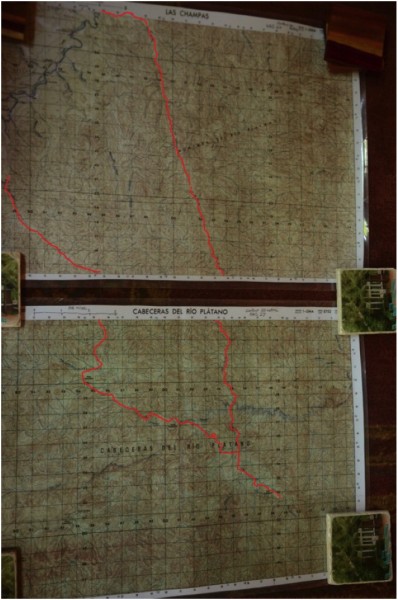

Figure 27 Basic route maps.