After a summer spent guiding at Castle Rock, playing disc golf, and sport climbing on the East Side, the urge to get up high finally manifested from deep down. With a gig leading hikers up Half Dome at the end of the week, good weather holding, and Leaning Tower in-a-push plans scrapped, the right moment for peak venturing presented itself.

Laurel Mountain had crossed my mind numerous times over the past few seasons--most recently back in June and July while clipping bolts and camping in the aspen groves of the Big Springs zone. Several rest hours were spend gazing out at Morrison and Laurel--the former resembling pillars of the earth and the latter seeming slightly more accessible. My friend James mentioned more than once how, among all the easy fifth class solos he'd done with Puhvel, Laurel was the one where he encountered an uncomfortable sense of exposure.

Game on.

Instantly, that comment rattled around my inner voice as a personal challenge. Now it would become a call to action. I booked out of Santa Cruz mid-Tuesday afternoon, intent on a Wednesday date with the route. Thursday was for rest. If all went well, Friday I'd meet my clients.

Five and a half hours down the road, I pulled into the Mobil and immediately ran into Tom Davis. Who else would use a pay phone to check wind conditions for a potentially epic paragliding adventure the next day? After chiding TD for not having a smart phone, he invited me up to his camp for post-flight, post-ascent spray. It sounded like the perfect conclusion, but I'm jumping ahead... Back in the present, I grabbed two Snickers for the send. The counter employee sarcastically reminded me to enjoy them, to which I replied, "Oh, I will." But didn't add, "for lunch on the summit." After all, no matter what snacks you carry, nothing is certain in the mountains.

After a soak in the Rock Tub and a solitary night's sleep next to the spring, I was up at six. Car packed, a quick breakfast of day-old, homemade blueberry muffins, and a gulped-down liter of water later, I hit the trail right at seven--Laurel just then catching a warm morning light.

Other than some pretty flowers and the hulking face of Laurel looming overhead, the approach proved unexceptional--a fairly flat trail around Convict Lake and an obvious drainage to the base of the route. The Croft guide stayed in my pack for the whole thing. As I got within spitting distance of the gully, though, I ran into this:

From below it looked like a pumice-mud arch. Rocks were actively falling from above, punching holes through it.

I'm not crawling under it, I thought.

It's clearly too thin to walk over it. Dammit! I'll rub some sunscreen in, put my helmet on, and then I'll have this figured out.

So I did, and I did, and I walked over the troll of the gully entrance, rocks speeding by, whispering "shall you pass?" As I came to the edge, I peered down into the small abyss, and jumped quickly with a mind toward a safe landing. Then I turned around and fully realized the core of what I'd negotiated.

Damn, that's some dirty snow! So, maybe this thing is gonna be a bit loose. Think I'll leave the helmet on for the time-being.

As others mentioned, the start of this route has a canyoneering feel to it. Indeed, as I entered the gully, I encountered several short steps between periods of easy scrambling. For the most part, I stayed in my trail-runners. As the steps got taller, and the rock no less dusty or slick, I started to crave sticky rubber. I laced up around something like this:

Soon the gully led to the slabs and some nice views down towards Convict Lake, Crowley further out, and the hot springs of the previous night.

Somewhere in this zone, I noticed that I'd left behind the semi-continuous showering of rocks. So I made a decision that would lead to a terrible mistake: I took off my helmet and clipped it to the back of my pack. I continued up through another gully-ish section--this time composed of red scree. Not too bad to negotiate, but worthy of the "pull down, not out" attention that Pinnacles climbers know well. Exiting this section led to the best rock of the route: gorgeous white slabs enhanced by a solid red vein.

In a perfectly enjoyable mood, I started to admire some of the blossoms, and paused at the top of the slabs to eat a snack and shoot the flowers for later identification:

Anybody?

I was on the edge of the final red-scree. A wiser climber might have read this as a sign. My helmet had been clipped to the top pocket strap. The helmet was now wedged between my pack and the rock, the top pocket being unclipped. Blame it on the altitude, blame it on my own forgetfulness, blame it on whatever. As I shifted my pack to put my camera away, my helmet came loose and went for a ride. I watched helplessly as it tumbled down all the slabs, into the upper gully, out of sight but not sound, and presumably came to a rest some thousand or so feet below my current position. My helmet! The precious brain bucket that had been apart of a streak of successful big wall ascents. My shell, with it's "organic" sticker on the forehead and In and Out sticker on the rear--to symbolize what's on the front and back of my mind. My white shield, no matter how uncomfortable it had become with age, had left me too suddenly. And what had it left me with? An impending sense of nostalgia and a loose section of crappy red scree to the summit. I said a quick goodbye and returned to the climbing. Now I'd especially little interest in spending much time in any more loose sections. I found a line of semi-solid looking red buttresses that, as it turned out, led straight to the summit. Somewhere among this mess:

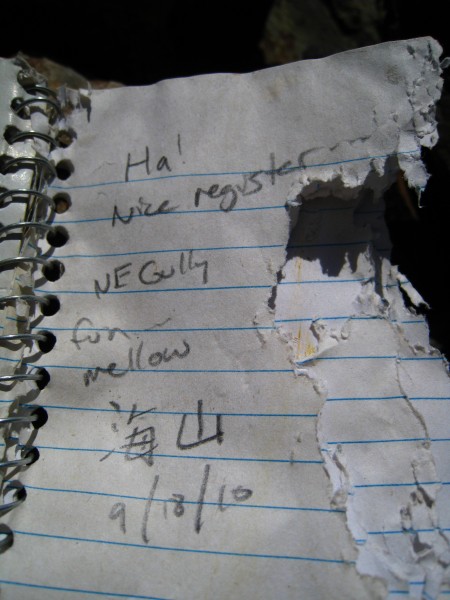

Soon I stood on top--no real register in sight, just a US Coast and Geodetic Survey marker from 1933 and (hidden under a rock) a make-shift notebook that had chew marks of marmot or some such high-altitude critter.

I wolfed down my Snickers, made some phone calls (ever wonder where you

can't do business these days?), and noticed the time. Eleven AM; not bad. Time to head down the forty two hundred feet I'd just come up. Of course, gotta admire the view first.

This is the point where I could probably double the length of this report and give some incredibly detailed beta on the descent. Given the history of unnecessarily long descents associated with Laurel, that might be a nice gesture. However, I think keeping it simple might work better. The Croft description worked great. I'd say the key phrasing "minor gully systems" was crucial. After scree slopes and following a bit of the ridge line that most closely parallels Convict Lake, passing what might be described as major gully systems, I chose this one:

I broke up good bits of scree skiing to admire some Blazing Stars (I believe):

In due time, I was back on the trail around the lake, running, and smiling all the way to the car. A time check showed just past 1 PM. I took a quick dip, and headed towards the warmer waters of the Hill Top tub. Later, I left a note on the Mammoth Mountaineering Shop lost and found board--a desperate attempt to seek reunion with my helmet.

Anyone?

Finally (you thought it was over?), I made it back to the Mobil. As I was ordering my carnitas tacos and beer, a familiar figure flirted with my peripheral vision. With a foot-high stack of to-go boxes precariously balanced in one arm, it was Peter Croft depositing a sizable bill in the tip jar. Before I could think of anything to say, he smiled and made a speedy escape to the parking lot. Funny, I thought, he's tipping the ones serving us; I should be the one tipping him.