Lizard Head Peak is the hardest summit to attain in the state according to the classic Ormes guide to the Colorado Rockies. Insofar as this refers to the summit of a peak, this is probably true, although the summit of Chimney Rock above Ridgeway surely runs a close second. One winter in the mid 1970’s Charlie Pitts and I decided to head down to the San Juan Mtns and give Lizard Head Peak a go. We had been there during a previous summer’s outing and been rewarded with a satisfying climb on rock that was surprisingly good by San Juan volcanic rock standards. The San Juan Mountains offers a smorgasbord of volcanic rock that ranges from bullet-proof densely welded intra-caldera tuff with the consistency of granite to poorly welded pyroclastic flows with the consistency of wet cat litter. Lizard Head Peak lies somewhere on the firm side of the median point between these two extremes.

The ski approach from Colorado Highway 145 west of Lizard Head Pass was as good as it gets. The snow pack was deep and solid, the trail breaking was easy, we were waxed perfectly for the conditions, and it felt like we had the entire county to ourselves. Charlie and I decided to go as light as we felt we could get away with, eschewing a tent in favor of a snow cave, and taking one rope and a modest rack of stoppers and hexes. This was during that period in our careers where we were particularly enamored with snow caves as winter shelter. Not all of our snow cave adventures had been raging successes but the Lizard Head snow cave was exactly the right application of this bivy technique. Since Lizard Head Peak lies on a high alpine ridge that drops steeply off on all sides, there are precious few flat places to put a tent anyway, and none that are out of the near-constant winds. With an investment of about an hour of our time we had established palatial digs on the lee side of the ridge just a few hundred meters from the start of our climb.

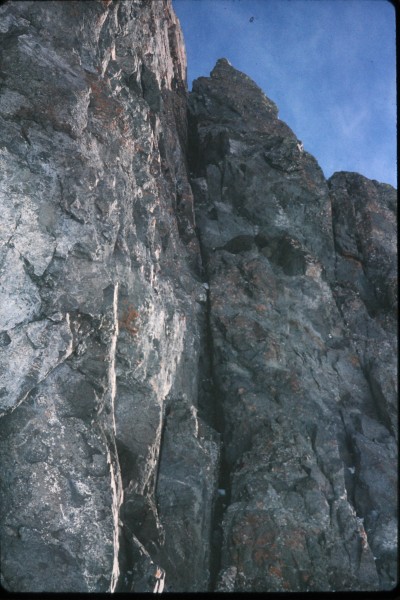

The following morning dawned clear, cold, and windy. After a pleasantly short approach march in the wind we arrived at a dihedral on the south side of the peak. Here the peak is composed of densely welded tuff that forms a vertical cliff on all sides. This dihedral goes for about a pitch and a half of 5.7 climbing well protected with nuts. The modest difficulty was a blessing because it was quite cold and we needed to climb with a combination of mittens and fingerless gloves or risk frostbite.

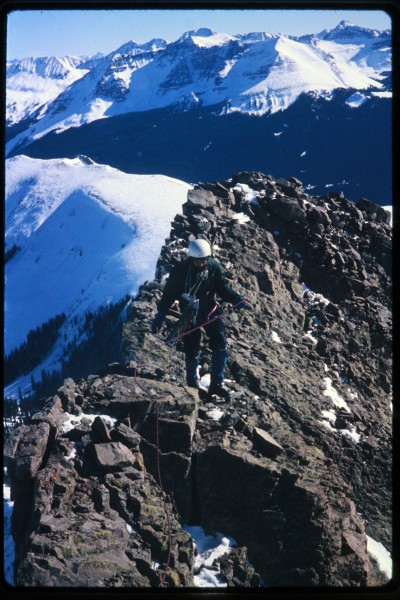

At the top of the second and shorter pitch, the welding character of the tuff changes and the rock forms a more chossy, boulder-strewn steep slope beneath the final headwall. Here we traversed around to our left on the choss to where an overhanging crack system leads through the final headwall to the summit block. This final steep pitch results from yet another change in the welding character of the tuff. Surmounting the initial overhang goes at about 5.8 and comprises the crux of the climb, with good protection available once past the overhang. Once above the overhang the climbing becomes much easier, with a flat but windy belay stance at the top of the pitch. From there it is but a short ridge scramble to the actual summit.

By midday we were at the top and quite pleased with ourselves. There was at that time an old tobacco can being used as a summit register, and we noticed that we had been beaten to a first winter ascent of Lizard Head Peak by Lito Tejada-Flores of “Guide to Ski Mountaineering” fame. Way to go Lito, you da man. It was windy, we were cold, and it was time to go. I snapped one more pic looking down the north face for future reference, since this was so obviously the steepest and longest line on the peak. It might make a reasonably challenging route in the summer, but would be a bitter cold suffer-fest in the winter.

After three raps on reasonable anchors we were down with several hours of good sunlight left to ski out by. The quality of the winter mountaineering was certainly matched by the quality of the skiing back to our trailhead. Truly, this adventure had hit all of the high points, leaving no fun-stone unturned. As an additional geologic observation, the Ormes guide also states that Lizard Head is a volcanic neck, which is not true. Ship Rock in New Mexico is a true volcanic neck whereas Lizard Head, although composed of volcanic rock, is an erosional remnant of intense alpine glaciation. The glaciers nearly won the day on this one as only a thin pillar of volcanic rock survived the headward erosion of three glacial cirques.