We – my daughter, son in-law, and selfie – have made 2 attempts on the “Classic” (read: crowded) East Arete.

And each attempt has ended identically, in unmeasured failure, pathetic retreat, and abysmal shame. This being a signature characteristic of this otherwise classic route, we've maintained our batting averages by avoiding this route closely. Next season, we plan to avoid this ordeal once again, to preserve our record for the most failures on the East Arete route.

In order to train for the East Arete, we've taken to the Northwest Arete, mostly for the exercise and fresh air. This photograph shows the SW aspect of the mountain as seen from “Camp 509.”

The fastest and least exhausting line of approach wants, I think, to follow the contact zone between the buff-colored granite of the upper 1/3 of the mountain's mass, and the dioritic plinth, deeply raked with steep narrow clefts and chutes, on which the summit formation bears.

Top of the Trough, start of the traverse out and onto the Arete.

Marmot Lake.

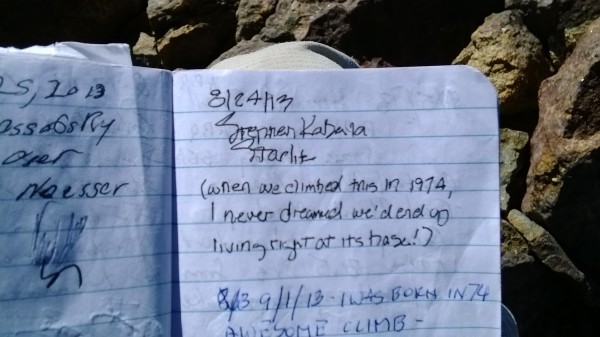

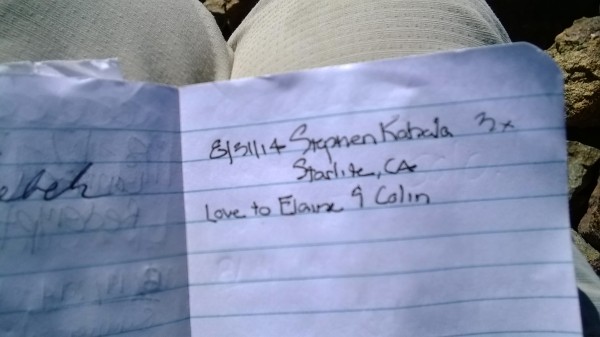

Note the Register entry below my own. It's kind of cool to carry a conversation along in the pages of the summit Registers...later, if you happen to know the climber you can walk up and ask him (or her) about their experience on Mt. Saint So and So.

Merriam; Royce; Feather (with Seven Gables on the horizon beyond); Hilgard; Julius Ceasar; Bear Creek Spire South Face; Four Gables.

The ridge connecting Four Gables to West Basin Mtn (next slide) is an excellent skywalk; largely level, and above 13,000'. The descent gully into the Upper Horton Lakes cirque cliffs out into 4th, heads up and maybe find a better descent.

Broken Finger; Adamson Mine; Mt. Wheeler; Round Valley Pk – are West Basin and Basin Mtn in the foreground with unidentified metamorphic pyramid hulking between and beyond them.

Lots of people get shut down at that East Arete satellite summit. Basically, the shortest straw gets you either the loose downclimb, or a snafu-prone rappel into the notch. Either way, it looks to be about 200 feet. There's enough foot traffic (is there any other kind up there?) to have formed a good use trail into the Clyde Route's South Gulley up to this same East Notch, and so when I fail to give the East Arete a try next season, it shall be via this approach.

There are a couple of climbers descending the upper East Arete in the photo. They're moving very slo o o w ly, which is probably why you can't see the guy in blue nor his partner in red and out on point. But what can you expect from a Telephone-Camera-GPS-Personal Mgr-internet browser? So convenient – I'm actually posting this trip report as we descend the West Ramp into Camp 509!

This might be one of the most intriguing reaches of the Crest, an alpine Bermuda Triangle which has captured my imagination and held it at Swiss Army Knife-point since the late 1990's.

As is plainly shown, the slabs and the meadows of Humphreys Basin slope gently to meet the Crest ridge. Then, in a hair's breadth, the floor drops out – 2,500' – 3,000',

instanter!, with this prominence then increasing quickly as would be expected from a thrust-block mountain range.

Once upon a time, a Civil Air Patrol rescue mission, based out of Fresno County, was recalled, according to our local newspaper, and an Inyo County air extraction team dispatched in its place. The confirmation of fatalities had eliminated the need for an urgent rescue response, and this response I interpreted to mean only one thing.

The vicinity where the missing aircraft's emergency transmitter had gone down, which here shows as the uppermost lakes in Humphreys Basin, is not in Fresno County but in Inyo County. This distinction becomes essential when the First Responders seek cost reimbursement from the jurisdiction’s funding agencies.

These lakes are not within the hydrology of Humphreys Basin at all. They drain southeasterly into Paiute Creek, thence Owens River, even as these headwater lakes appear to be ensconced at a somewhat higher elevation than their neighboring lakes in the Basin drainage proper. This also means that no part of Checkered Demon, Mt. Emerson, or their interconnecting ridges, occupy the Crest - they're outset.

A quick armchair examination of the USGS topo quads will corroborate the true hydrological divide of the Paiute Pass vicinity. It was much more engaging, though, to field verify the existence of a white area on local maps and lore, a sort of “Bermuda Triangle” close at hand. Setting action to words garnered the 2nd ascent of one of Mt. Emerson’s northwest satellite towers, in about 2002. Some of Mt. Emerson's satellite towers and outliers had been identified as prospective climbing objectives in the 1954 through the 1963 Hervy Voge "High Sierra Climbing Guide" editions. Perhaps this tower was one of these problems?

One of the lakes down there is good old Camp 509. In fact, it's pretty easy to identify from an aerial perspective.

It's not until you're back on the ground that the full scale of the labyrinth becomes apparent. Each lake, or tarn, is ensconced in a miniature basin-and-range drainage pattern all its own. The lakes might be quite close to one another, but lie at differing mean elevations within separate micro drainage basins, with no interconnecting streams between adjacent lakes or master watercourses. These lakes are situated in bowls which may have a relative depth of bout 100 feet.

Each lake, and its watershed, presents as a stereo-isomer of each its neighbors, greatly complicating cross country travel navigation.

All of this means that you can't see from the depth of one bowl into another, and, from the tops of the ridgebacks which form the localized watershed boundaries, there's little line of sight communication possible between bowls.

So the only way to check your bearings with any degree of precision is to ascend about 100 feet from the talus shore of the one tarn, and then descend about 75 feet to the shoreline of the next tarn, to find it very analogous in appearance to the tarn you've just traversed.

The relative success of the snowpack survey stake #509 in helping confirm the identity of the proper Base Camp lake depends, of course, upon travel during daylight hours. August 2013 would have gone better had I troubled myself to set down the coffee 30 minutes earlier that morning.

"An hour in the morning is worth 3 in the afternoon" goes the old expression - I've recently acquired the habit of inventing 'Old Expressions,' and the source of that one is probably the guy who also claims that "1 mile of cross country is worth 5 miles of trail."

Noted that such pearls are irrelevant to a team up to climb say, something on the Apron, or similar projects which make up in technical difficulty what they lack in way of a true summit.

In this instance retreat is effected by rappel, and the summit is simply a matter of choosing the optimum ledge to represent the day's high point. Headlamps are useful at dusk, when a field of vision which only needs to include hardware and some sense of direction towards your car.

When the day's objective is not your car, in a roadhead parking lot, but a small dark pack next to 1 of 10 identical small black lakes, and the means to get there safely involves more gravel than trail, a grasp of a consensual reality is all that's necessary to understand which creature comforts may be sacrificed in order to survive the day and see another.

And while a headlamp can illuminate trail-less sand and gravels at foot level, it's a puny defense against all the man trap potholes, caves, and sudden cliffs which landscape this alpine Bermuda Triangle. At this point, a broken ankle, or worse, is less a possibility and more a statistical probability. And so this night was spent out in the open, an unplanned shelterless bivouac above 12,000'.

As a first time experience, it wasn't too bad. This year, though, would have made 3 climbers miserable instead of just 1, and since one of these persons would be my very own daughter, it wasn't happening.

And all that was needed this year was a slightly earlier start, a light hearted but pointed morning motivational talk, and a consistent cadence throughout the day:

"Slow and Steady wins the Race."

All of our cameras were too crude to capture the Coast Range mountains distant but visible way out west. Like Mammoth Mtn, there are few obstacles to the Pacific storm track, so if it's snowing anywhere in the Central Sierra other than Mammoth, its going to be dumping into the Humphreys east cirque, perpetuating a cycle of glacial quarrying; strong wind rotors to precipitate greater snowfall yields, etc.