NA Wall – Second Ascent

Dennis Hennek and I began climbing together at Stoney Point back in 1962. He, BooDawg, and Life-is-a-Bivuoac were high school seniors at Canoga Park High School and we all had just begun our lives as climbers. They were 17-18, I was 29-30.

That year I moved my family 50 miles from East Anaheim into a new, not quite finished, tract home in Canoga Park just to be close to Stoney. The three of us met often at Stoney and became regulars there along with Kamps, Higgins, et al. We also all became life-long friends.

I got my first taste of Yosemite wall climbing in 1965 with Kor on the third ascent of the Leaning Tower. Did the sixth ascent a few months later with Boche. Hennek and Boche put up a new route on Sentinel’s north face in September – coincidently, at the same time, Conrad Willet and I, along with Schmitz and Madsen, were all on the north face doing three separate routes. We all summited the same day. I didn’t do any Yosemite climbs with Dennis until November of 1966 when we did the Leaning Tower – my third time up (I've done it three more times since). That year I did the NW face of Half Dome with Chuck Haas. Dennis and I were gaining some wall experience.

Hennek and I only did a couple of Valley climbs in 1967 – no walls. But early that year Boche and I had done the eighth ascent of the Nose. I was ready for more walls. So was Dennis and we decided on the third ascent of the Dihedral Wall of El Cap. In September we completed the third ascent. We were a perfect team and were beginning to think of bigger things. What better than “the most difficult rock climb in the world” according to Royal Robbins – the North American Wall.

We studied Royal’s topo of the climb, read and re-read his account of the first ascent in the American Alpine Journal - to this day, 1965 is the most dog-eared copy of the AAC Journal in my 57 years of membership. We spent days at Stoney nailing every decent crack we could find. On the Dihedral Wall we had developed routines for handling the setting up of belays, hauling, switching leads, and checking each other before parting company at each belay – “I’ve got my own personal Jumars, I’ve got my own personal pulley, I’ve got my own personal belay seat, my own personal … etc.”

We knew our limits when it came to hot weather. We planned on 5 days; that meant at least 5 gallons of water – a liter each during the day, a liter each during the night. I sewed up a haul bag to specifications that met our needs. It had a square bottom that was designed to hold four 1-gallon plastic containers side by side forming a square to fit snuggly in the bottom of the bag. The straps used to connect the bag to a locking carabiner were long enough to allow entry to the bag at a belay station and sewn only across the flat bottom to prevent wear. The second man on each pitch carried a La Fuma rucksack with 2 liters of water, snack food, and extra clothing.

Very early on April 7, 1968, Robbins bid us good luck as we parted Camp 4 with our gear. Sandy Santibinez helped us lug the gear to the base. We were off and running on the first four pitches of hard nailing to Mazatlan Ledge. I took the first pitch, Dennis the second – all without a problem. It went quickly. I was a little anxious about the A5 third pitch, but, again, no problem. We climbed the crack off of Mazatlan and Dennis led up a bolt ladder on the way to Easy Street. Half way up the ladder one of the bolts pulled and sent Dennis into a swinging fall that slammed his back pretty hard. “You okay?”

“Not really. My back hurts.”

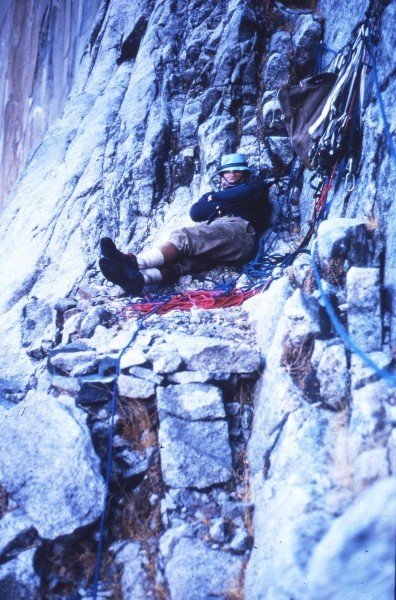

Easy Street - comfy bivouac

Credit: Dennis Hennek

Regardless, he led on and we arrived on Easy Street as the sun was setting for a very comfortable bivouac – for me. Dennis’ back was bothering him.

In the morning the lead off of Easy Street was mine and I was just nailing away up this right leaning groove when as I began driving in a piton the granite in front of me shifted. Oops! I dared not hit the piton again and I dared not try to put my weight on it to enable me to nail on past it. I was stymied. “What’s the problem, Don?”

“This block in front of me just shifted and if it breaks loose it’ll take out my belay rope and land on you!”

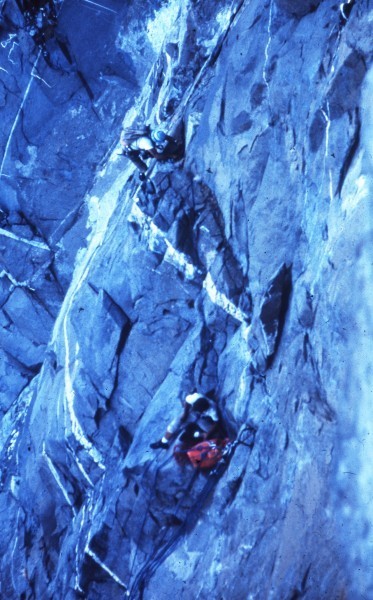

Dennis after launching the block

Credit: Don Lauria

Dennis nervously began squirming at his belay station, “What can you do?” I knew what I had to do and got out the bolt kit. I could reach the solid granite above the block, so that’s where the bolt went. Supported by the bolt, I could reach beyond the block to continue nailing the groove. “Whew!” Now if the block would just stay put until Dennis got past it we were safe. Dennis ever so cautiously began to follow my lead. When he got to the bolt he screamed loudly “rock” and gave the block a tap. Off it went, all four feet of a two-foot by three-foot hunk of granite. It made quite a bit of noise as it made its way to the base. From below came a cheer from a group of spectators led by Royal.

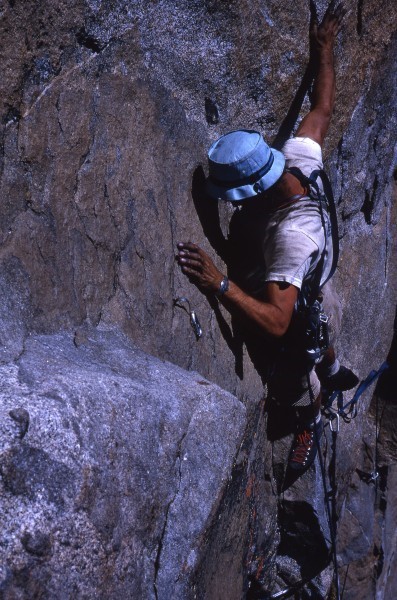

We reached Calaveras Ledges before noon. When I finished following the pitch and began sorting hardware for the next lead, Dennis announced, “That’s it. We’re going down, my back is killing me.” I did not want to bail and began pleading with him to stick it out. My plea was answered with the sound of water splashing on granite. “We’re going down, Don.” Dennis began to pour out the second gallon of our remaining two water bottles. Yep, I guess we’re going down.

Here goes the water

Credit: Don Lauria

We rappelled off. Royal met us at the base with a sort of smirking grin. “Have a little problem up there, boys?

“Yeah, why didn’t you tell us about that huge loose block?”

“Oh yeah, the block. Thought you should figure it out yourselves,” says Royal with a sort of smirking grin.

Okay, we failed, but only because of Dennis’ injury. We’d be back! Meanwhile, despite his back problem, Dennis and I remained in the Valley for four more days. We climbed each day, two of them with TM. Two 5.7s and two 5.8s. I guess Dennis’ back was better.

Back to the drawing boards. We decided to wait out most of the summer, let Dennis heal up, and go back at it later.

I arrived back to Yosemite on August 28. Climbed a couple of days in Tuolumne, then headed for the Valley. Dennis was already there and so was Royal. He knew of our plans and was anxious to see us off – or so we thought. More on that later.

Royal was hanging out with a British climber – Ed Ward-Drummond. It seems Drummond had arrived from Britain with intention of doing the NA Wall and not being able to find anyone to climb it with, he was going to approach us. Royal knew this and two days before our intended start, he asked if we would like to do Bridal Veil East with him and Drummond (or Ward, he kept switching his name around). We did the climb and Ward never stopped pleading with us to let him go with us on the NA. We were adamant – we are a two-man team - we’ve been planning this for a year – another climber would slow us up and we don’t need anyone else. The answer is “No!”

On September 2, we started early. The first two pitches went quickly. Again, the third pitch, the A5 pitch, (“the hardest aid pitch of my experience” – Yvon Chouinard) was my lead. I had led this in April with no problems. This time there were problems. Lots of problems. When I got to the thin part of the crack, after placing about six or so tied-off knifeblades and rurps in and then stepping up on to the seventh pin, it would pop. Since the knifeblades were all tied off, I lost all of them into the abyss and found myself quite a bit lower on the pitch. Okay, second try. I know I could have secured the knifeblades with nylon, but that takes time and I was in a hurry. I’ll just be more careful. Second try, same result. Hell, I led this thing in April with no problems, so everybody knows I did it once. F#%k it. Out comes the bolt kit. So I defile the pitch with a bolt! I know someone’s going to chop it and get by this, but I’m in a hurry. And I don’t want to lose anymore pitons.

Dennis following 1st pitch - can you pick out TM at the base? He also corrected my statement below. Not Calaveras, but Big Sur Ledge was our bivouac.

Credit: Don Lauria

Onward. We reach the bolt I placed to get rid of the block in April and I could have chopped it since it was no longer necessary, but I didn’t. When Dennis reached me after following it I asked him if he chopped it. “What bolt? Oh, damn, waltzed right past it. It’s way above the groove. Missed it.”

We had our second bivouac on Big Sur Ledge(next ledge after Pour Out the Water Ledge). In the morning, Dennis led Frost’s slingshot pendulum and I followed with another pendulum. After many tries. I had to stop and just hang at the end of the rope to rest. The next attempt succeeded and we were on our way into the Black Dihedral. The days were getting warmer.

Our plan was to camp at the top of the dihedral in the Black Cave - scene of the classic Pratt photo of Robbins, Frost, and Chouinard stacked up in hammocks. We nailed it up tight and settled into a very comfortable bivouac. Peering over the hammock border was thrilling. Totally overhanging. Nothing between us and the ground - nothing. One of our treasured delights every evening was one navel orange each. It was dark when I was pulling two oranges out of the haul bag and clumsily dropped one into the “nothing.” No way was I going to tell Hennek. We’d just come up one short on the last night and I’d give it to him. Problem solved – maybe.

View from the Black Cave

Credit: Don Lauria

[Edit this Photo]

Hennek took the Pratt lead out of the Black Cave early the next morning. It was getting warmer each day and today it became a problem. On the next lead I began to feel the heat. Dennis led the next pitch to a ledge belay. By the time I got to him I was nauseous, lightheaded, weak, and very hot. The daily temperatures in the Valley were in the 100s – up here in the oven, it was way hotter. I had to rest – to recover from heat exhaustion. We had experienced the same calamity on the Dihedral Wall, but in that case it was Dennis who suffered. But we’d been there, so we knew what to do. First, water. Second, shade. We were on a roomy ledge, easy to sit on, so we pulled out one of our hammocks and held it high over our heads for shade. A little candy. More rest. A little water. An hour of climbing time wasted. Recovery and onward.

We got into the Cyclops Eye very late due to my affliction. There are no real bivouac ledges in there – certainly none for two climbers. The lack of accommodations meant separate rooms. We were separated by half a rope length and just trying to find a comfortable position for the night, when literally, out of the blue – actually it was more out of the gloom than the blue – came Sheridan’s Superman. Royal Robbins was down for a visit. The paparazzo had found us. He was on a long rappel and shooting pictures of us in our precarious positions. After some brief chatter, we bade him adieu, and his lordship ascended. When I revealed that I had dropped one of our oranges back in the Black Cave, Hennek didn’t believe me. “You ate it didn’t you? You ate the damn thing.”

“No, Dennis, I dropped it. You can have the last orange.”

Realizing I was being truthful, we shared the last orange. Ahhh … wasn’t that sweet?

Cyclops Eye looking for a room - RR Photo

Credit: Royal Robbins

The lead out of the Cyclops Eye was rated A5. It supposedly required some sky hooks and we were prepared with a Dolt Cobra – a sky hook with an attitude. It was my lead. We wanted to reach the summit that day so we decided to start very early. With my trusty Dolt Twinkledolt, I embarked on a wild lead into the dark. Twinkledolts were headlamps that defied description, but I’ll make an attempt: A band of stretch material, probably a discarded elastic bandage, had glued to it a bare lamp socket, like those found in the interior old flashlights. A thin wire, about three feet of it, ran out the back of the socket to a bare plastic battery holder of two AA batteries. The lamp bulb was of the focusing type – it concentrated the light beam in front of the wearer. One turned the bulb clockwise to complete the circuit, counterclockwise to kill it. Extremely lightweight on your head, even by today’s standards and they worked. The battery pack was carried in your pants pocket where the weight was of no consequence.

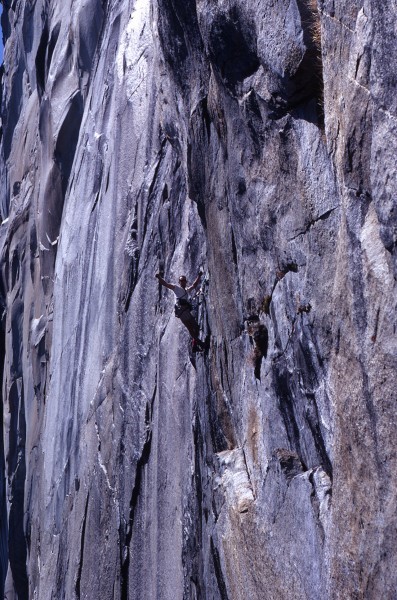

A5 Traverse

Credit: Dennis Hennek

The lead was a straight traverse to the right along a crystalline dike. The protection was difficult to place because the gap between the dike and the main wall was practically non-existent. When I couldn’t get anything in, I used the Cobra. I had to leapfrog the skyhook because we only had one. After forty feet of horizontal traverse along the dike, I reached a dihedral that was easily nailed. I have a photo of Dennis following this and even though he was at least sixty feet away you can tell in the photo he was scared she-it-less. Following a traverse with questionable protection and a few gaps creates visions of slamming into the end of the pitch. I was as scared as he was.

Dennis following traverse. I don't have the "scared" photo digitized, but notice that I'm also belaying directly with the haul line. Not sure it would have lessened the pain if he zippered the pitch. Just made him feel better.

Credit: Don Lauria

Then having just survived the traverse it was his turn to lead. To lead “the overhanging sand dune” as Chouinard labeled it. Loose overhanging blocks – large blocks – with sand filtering down with each hammer blow. He did it without a whimper. I had visions of TM leading this. It would have been worth the price of admission to listen.

The next lead was one of Pratt’s and was vaguely described in the Journal. I began the lead by intricately threading the rope through the protection to create the most friction possible and found myself free climbing, standing in critical balance, both arms outstretched left and right, trying not to allow the rope to pull me over backwards. Slack Dennis, dammit, slack! Add to that, superman reappeared and started recording my plight without the least interest in giving any advice – figure it out Don! I finally hooked a flake with the Cobra, got back in my etriers and gained an acceptable sling belay.

Got no advice from the photographer

Credit: Royal Robbins

The rest of the day was spent traversing below the Igloo with the Fresno Bee’s ace photographer adding to his booty. When we reached the Igloo, Robbins had re-positioned himself to catch us finishing the route. I did some free-climbing out to set Dennis up for the final overhang. Robbins bagged the cover shot for Mountain Magazine – Hennek hanging from a rurp struggling to place another piton at the crux.

Fresno Bee's ace photographer

Credit: Don Lauria

Cover shot by Royal

Credit: Royal Robbins

We were up. It was late on September 6, 1968. There were no TV cameras or reporters on the summit, save Royal. He left immediately – had a deadline to meet. There were some of our friends and lots of beer and champagne. We were stoked. It had been four years and two months since the first ascent. We had just done the second ascent of “the most difficult rock climb in the world”.

Nice to have friends on the summit. Taste in beer hadn't matured - craft beers didn't exist.

Credit: Don Lauria

An aside: North America Wall or North American Wall? Even Royal has printed it both ways. It's still the same wall. I just thought I should bring it up before someone started a thread on it.