The tallest peak rising from Garner Valley is Tahquitz Peak and its southeastern slope is covered with rocky escarpments and a few large rock faces that are heavily guarded by miles of dense shrubs. At around the 8,000 foot level is a large, triangular shaped face that, from afar, appears to be a few hundred feet high with a distinct, large triangular block on top. After living in Idyllwild for a few years, I became interested in exploring some of these larger formations; and on one afternoon in the summer of 2013, I hiked out to this particular face on the south side of Tahquitz.

In the weeks before I hiked up there, I asked around town for any information on the formation. My friend Clark immediately knew the formation I was describing and said it was named King Farouk, after a comic strip character that had a similar triangular profile. Excited that he had been there, I asked him several questions and he readily shared what he knew.

Clark told me that he and a buddy decided to climb a route on it sometime in the late 70s. They hiked up South Ridge to Tahquitz Peak the evening with a rope, a rack, a few bolts, food, and sleeping bags and spent the night on the summit. The following morning, they hiked down from the peak to the base of the formation with their climbing gear and looked for a route. Clark said the route they chose began on the top of a large boulder at the base of the formation, just left of center. According to Clark, the route ended up being two pitches, required a few bolts, and went at about 5.9. After topping out, they returned to the summit to grab their packs and hiked out.

It was cool to learn a little bit of history about the formation and, according to Clark, his route was the only route on the face. I was excited to check out a huge face of rock that was virtually unexplored and planned to hike up there in the coming weeks, but I needed to determine how I’d get there.

I was not very interested in hiking to the summit of Tahquitz and then dropping down to King Farouk. Having done a fair amount of bushwhacking around Tahquitz, the thought of dropping down didn’t seem appealing. I didn’t want to get cliffed out on the way down and I wasn’t excited about committing myself to vertical bushwhacking to get out. I wanted another option.

While studying my topo map and looking at the area on Google Earth, I noticed that the base of King Farouk was on the same level as the saddle formed between Tahquitz Peak and Red Tahquitz. I made a plan to hike up Devils Slide and turn south on the PCT for about a mile before moving south off trail towards the saddle between the two peaks. Then I would contour west along the mountainside until I hit the formation.

With a definite plan in mind, I chose to go check it out one afternoon in July when it was too hot for my regular solo circuit on Tahquitz. I loaded a small pack with my 2.5L hydration bladder, a snack, my cell phone, and a pocket knife. I drove up to Humber Park from town after lunch and began hiking up the trail around 1:30. Travelling light, I tried to hike up the 2.5 mile, 1500 foot elevation gain of Devils Slide as quickly as possible. I made it to Saddle Junction in just over 35 minutes. I was dripping with sweat and breathing hard from hiking so quickly and because I was in full afternoon sun for the whole climb.

Once on the PCT after Saddle Junction, I slowed my pace a little bit. The air was cooler up higher and there was a slight breeze, which cooled me and my sweat drenched shirt. When I reached the junction for Tahquitz Peak, I went off trail towards the saddle between Tahquitz and Red Tahquitz, just as I’d planned. The terrain was much more rolling than it looked on a map. I lost a few hundred feet of elevation before having to climb back up to the saddle. The forest was pretty open here and other than having to empty my shoes every few hundred yards because of the soft, sandy soil, the walking was easy.

I eventually made it to the low point between the two peaks and began contouring west. The forest was very different on the south side of the mountain. There were many more pine trees, manzanita, and other low growing shrubs that made cross country travel annoying. At times, I found myself wading through pine needles up to my knees. The hillside was pretty steep and I often found myself “cliffed out” on large boulders, either having to backtrack a few yards or down climb bushes and tree limbs to progress. After bushwhacking for a while, I realized that retracing my steps through this would not be fun or as easy as I’d hoped, but at this point I was committed. I kept going and about 45 minutes after leaving the trail, I made it to the base of King Farouk.

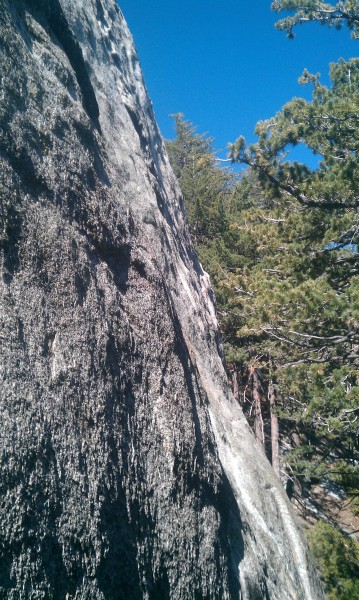

The face looked huge! It reminded me of walking along the base of the Sunshine Face at Suicide Rock. The base was relatively level and covered with a thick layer of pine needles. The face was very smooth and nearly vertical for 30 feet or so all along the base. Wandering around, I saw almost no obvious lines of weakness to be climbed along the right side, just smooth granite. It looked too steep and featureless for anything under 5.11. Moving further left, the base started to climb steeply up and there were a few large boulders. Scrambling around and up, I found myself on the top of the largest boulder touching the base of the King Farouk. Right there, at head level was an old, rusty bolt. Clark’s route! The bolt protected the opening moves off the boulder, which would immediately put the climber 20 feet above the ground below. A few edges and slopers lead up to the lower angle, highly featured granite above.

From my perch atop the boulder, almost the entire rock face was visible and it’s defining characteristics obvious. The bottom 20-30 feet of King Farouk were very smooth and nearly vertical, while the remaining 150-200 feet were somewhat lower angle and highly featured, resembling waves on a lake. No cracks or expanding flakes were visible. I wasn’t able to spot any other bolts on Clark’s route up the face, but it seemed like the possible routes they could have taken were nearly limitless.

Continuing up and left along the base, the angle of the face gradually decreased and the number of features increased. There seemed to be a number of potential routes along this 50 foot section of the cliff, but most of them appeared like they would be indistinct after 20 feet or so because the rock above was so highly featured and low angle.

At this point, I had to make a choice whether to return the way I came or to find another way back. Reversing the bushwhack I made on the way in did not seem appealing so I began looking for other options. I continued left around King Farouk to see if there was an easy passage up the gully on its left side. The gully looked do-able. There was a fair amount of rock that I could scramble on, but it was otherwise filled with manzanita and a few pine trees. I decided to scramble up so that I could see the top of the King Farouk and also in hope of avoiding some bushwhacking.

The scramble started out nice enough but I soon found myself on some steeper-than-it-looked-from-below decomposing slabs. Like an idiot, I decided to push on. I remember trying to traverse around an awkward bulge, my left hand jammed in a rotten crack and my feet skating on the grainy slab, and thinking to myself, “Nobody knows where I am and I don’t have any cell service. If I blow this and break a leg, I’ll probably die a slow death tangled in manzanita.” Fortunately, I didn’t blow it and I was able to climb around to more solid terrain.

In between fearing for my life, I took time to notice the walls of rock on the left side of the gully. These seemed more appealing to me to climb than King Farouk itself because they were covered with vertical cracks about 100 feet tall, just begging to be climbed. Too bad they’re so difficult to access.

The top of King Farouk has a spectacular view of Garner Valley. The prominent summit block was relatively easy to reach, involving one exposed class 3 move. There was no summit register, cairn, or other sign of previous travel and I left it that way. Climbing down below the summit block, atop the main slab, revealed that the face of the summit block was covered with black, diorite knobs. The block itself reminded me of the Piasano Pinnacle on Suicide Rock; it overhung the main face of King Farouk and was relatively steep. A few bolts on the face would make for a route with spectacular position.

After I was satisfied with my exploration of the area, I bee-lined it over to the east ridge of Tahquitz Peak and followed it for a while before heading down and north towards the PCT. Once I reached the trail, I emptied my shoes of the pound of gravel and pine needles I was carrying in them. I hustled back down to my car and then into town for a beer.

At the bar, I met Clark and showed him the photos I’d taken earlier that afternoon. He seemed happy to see that his bolt was still there and he shared more information about his route. His partner led that first pitch and he said the first move was probably the crux. Clark led the second pitch and he said there may have been a 5.8 move somewhere, but otherwise it was pretty easy going. After topping out, they left and never came back.

I’ve explored several other major formations around Tahquitz Peak and Marion Mountain and put up a few routes on some of them. There is so much rock up here, you just have to be willing to get to it. Almost every one of the larger formations I’ve checked out has at least one, rusty, ¼” bolt on it somewhere, a testament to how prolific the climbers of the 70s and 80s were in this area. That said, there is still plenty of “new” rock available in Idyllwild to anyone willing to get there.