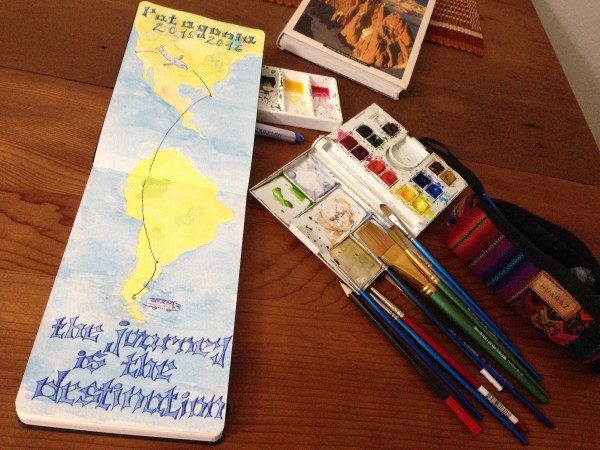

After three flights, a restless night in Buenos Aires, and a shuttle ride from the El Calafate airport, my partner and I arrived, deliriously tired, at our modest hostel in El Chaltén, 350 days after we had started planning our trip to Patagonia. The hostel kitchen window looked out onto Fitz Roy, which was more humbling and spectacular than I had ever imagined. Although the weather didn’t look stellar, it didn’t look dangerously bad either, so we decided to gear up. Our room hadn’t been vacated, so we set up our tent and a literal yard sale behind the main house. As we packed, another Californian climber staying at the hostel came by to watch the spectacle. He had a rope coiled on his back and had just spent the day cragging on the edge of town. It was his fifth season in the area and fortunately for us, he was generous with information. After dinner, he walked us across the main road to the northern stretch of Ricardo Arbilla to Oxalís, the taxi company accommodating alpine starts. It was 400 pesos to Puente Electrico, the trailhead for Guillaumet, but apparently the cost changed every season. We ordered a pick up at 3am, five hours from then, and retired back to our tent for another night of tossing and turning.

It was already raining when we got to Rio Electrico around 4am. We followed the river west to a crossing and onto a trail for a few flat miles to Campamiento El Fraile. El Fraile was on private land and along the way, there was a sign that read, “500 pesos to pass and 200 pesos to camp (pass included).” I was happy to be hiking in trail runners; though we had acquired some new gear, we had mostly pieced together our setup from what we had and we were heavy. After Fraile, the trail continued up steep switchbacks along the edge of a forest, to a plateau. We dropped our packs in the forest where we would spend the night protected from the weather; I put on boots and we continued up through a talus slope to Piedra Negra. We encountered a couple of climbers who were on their way down. One had tried to solo the Amy Couloir and another party had tried the Comesaña-Fonrouge, but had turned around because of snow. No one had summited and the weather was getting worse. We had left our goggles in our packs down below and icy drops stung our eyes. Snow collected quickly making it impossible to pick out the unfamiliar trail through the talus. We turned back to camp, hoping the morning would bring better weather. The next day, we ventured back up the obscured talus. At the snow slope below Guillaumet Pass, we put on crampons. By that point, the precipitation had started again and we turned back shortly after being funneled back onto the talus just below the pass.

On the descent, I was grateful for my trekking poles. A couple times on the switchbacks, the wind was so strong, I had to flatten myself on the ground not to be blown over. Back at the bridge, we hitched a ride, which saved us from the fifteen-kilometer walk to town or from calling a taxi from El Pilar, a hotel nearby. We arrived at the hostel just in time for a Christmas asado feast and to learn how to make empanadas and drink maté with our new friends.

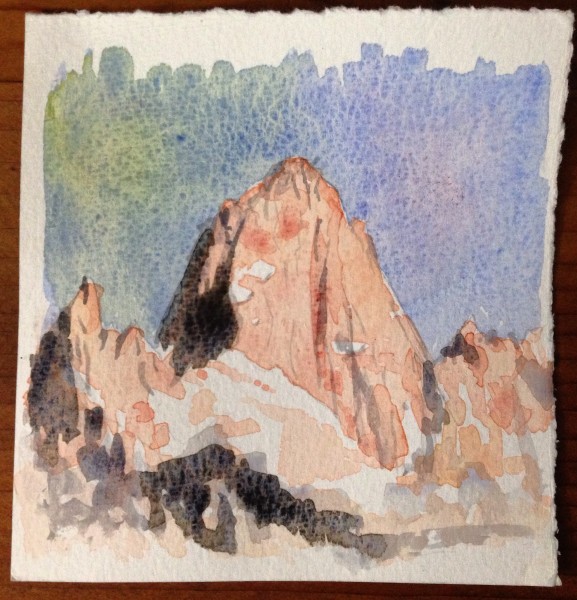

It started snowing in El Chaltén on Christmas Day and cabin fever set in. Hard. We sat around in the kitchen for days, eating, learning Spanish, waiting for the weather from NOAA to load, waiting for the data to show that the pressure was rising and the precip was going down, for the weather to change, to be good enough for long enough to climb something. We were completely controlled by the weather. The wind howled outside. It rained. It snowed. We commented about the changes in the type of precipitation falling, “Now it's raining, now it's snowing. Now it's raining again.” We bundled up occasionally to go into the tiny touristy village, to pick up groceries or sit in the lobby of La Aldea, write or paint, treat ourselves to dinner at La Braseria. We sat around, dreaming about long approaches, steep passes and slopes, river crossings, and navigation across glaciers. Miles and miles (no one ever seemed to know or care how many) and thousands of feet of elevation gain. We dreamed about climbing, succeeding or failing, to reach a summit of something, anything, then rappelling and turning around. Back. Back down the passes, over the rivers and glaciers, back to the luxury of the kitchen in El Chaltén, to do the whole thing over again. Do it again and again, for as many wonderful days as we’d managed to eke out from our normal existence.

Then, the weather changed. We had one or two days to decide how many pairs of sock liners to bring and which gloves and which gear. When we got back up to Piedra Negra, we were the only ones there until another party arrived. And another. And several more throughout the day. All with our objective: the Amy Couloir. We made a last-minute change of plans to a rock route, the Brenner-Moschioni, to avoid the crowds. We hadn’t brought enough food (again), so we were fatigued as we started up to the pass before sunrise the next morning. There was a bit of easy technical traversing to climb over the pass. When we got to the start of the Brenner, there was already a party on the route and another at the base. The party at the base decided it was too cold to climb, so we started ahead of them. After about a pitch, the party above us rapped. We were alone on the route. The climbing was really slow—hacking ice out of cracks with the ice tool—and the rock was generally covered in snow. My feet froze in rock shoes and the wind ripped, so I changed into mountaineering boots and left them on for the rest of the day. We bailed after pitch five from the thin crack, third from left. I struggled with our two ropes as I set up the rappel and they got tangled in the wind; as I rappelled, I came to an overhand knot. I felt like I had ten years before, when I first started climbing; I was humbled by the overwhelming nature of it all, but happy we had gotten on our route and made it down safely. The next morning, we ran up to Paso del Cuadrado for spectacular views of the Glacier Fitz Roy Norte and the west side of Fitz Roy, an amazing way to spend the last day of 2015. When we arrived back in town to another asado feast, a celebration of New Year’s Eve, we learned our friends had had similar experiences with the ice and cold weather.

We were grateful for the rest while it rained over the next few days until: “Window of the century!,” as described by an Alaskan climber when we met him on the trail out to Niponino, the camp at the base of El Mocho in Torre Valley. Though the approach was much longer and more involved than the walk to Guillaumet, we had lightened our loads considerably (only one sleeping bag for us both, no ice screws, less gear) while taking more food.

There are two approaches to Niponino, on the northern and southern edges of Lago del Torre. We took the southern route: nine kilometers along a trail, across a tyrolean, along the edge of the lake, down a steep, loose slope, and then onto the Torre Glacier. (There is no good beta for the approach. Unless you want to hike for twice as long as you need to, go with someone who knows the way the first time. We didn’t heed this warning and an approach that can take six hours took us a lot longer.)

The next day was windy and restful. We were considering a route on El Mocho because the approach was shorter than anything on the Fitz Roy Massif and we yearned for success after two attempts at Guillaumet. We felt every decision would either bring us closer to or further from a summit. I had my eyes on the Fitz Roy summits, though, and we decided to try for De l’S. We headed up through the moraine to high camp at Polacos in the evening. We had learned a lot in the two previous weeks: save on weight whenever and however possible, but don’t skimp on food. We ate a big dinner and crawled under a rock to sleep as the sun dipped behind the Torres across the valley.

Our objective was De l’S by a forty-five-degree, 300-meter snow couloir to the top of Austríaca, a route that seemed the surest for a summit. The approach to Col de los Austríacos was an alpine ramp that took us across the bases of Poincenot, Rafael Juarez, and Saint Exupéry. As we were putting on our crampons at the start of the couloir, a solo Lithuanian climber, Gediminas, strolled up. His cheerful demeanor was a welcome addition and we teamed up as a party of three for the remainder of the climb. At the top of the couloir, we climbed around a cornice and did a short approach pitch on rock. Traversing the saddle brought us to three glorious pitches of crack climbing to the summit. We reached the top around 1pm, the sun shining on our smiles. We ate a summit alfajor, enjoyed the views of the valleys and Lago Sucia, and set up the rappel.

The walk back to town the next day, the day before our flight out, was tremendously rewarding. As we crossed each major section (the moraine, the glacier, the moulin, the loose slopes, the tyrolean), making it closer and closer to El Chaltén, my deep satisfaction with our trip set in. We had taken our experiences, learned from our missteps and the conditions, and accomplished an objective. Though our route was neither the hardest nor the longest, we had managed to tag a summit in Patagonia.

In all, we spent eighteen days in Patagonia, ten of which were in the backcountry. We were truly lucky for the good weather and grateful to have met so many talented climbers along the way. Special thanks to Dan, my manager, and Linda, our teammate, for picking up my slack at the office while I was gone and to the American Alpine Club and the North Face for the generous “Live Your Dream” grant. Shameless plug because I had such a good experience: the application period for the 2016 LYD Grant is open until April 1, 2016 at AAC LYD Grant.