Shiprock has been a dream of mine since I began climbing nearly 15 years ago. But it has always been one of those semi-dormant, slow-burning dreams. Never a sense of urgency, but nevertheless sitting there, itching away, in the back of one’s mind.

My priority has been more technically demanding challenges. It is remote relative to other climbing destinations (and pretty much any place I’ve lived). The rock is loose, and the climbing is not free - the standard route up the formation involves a rappel which technically makes the route an aid climb. And finally, and perhaps most importantly, the legality of climbing it has been unclear, which, honestly, was less of a concern to me than upsetting individuals who might consider the rock a sacred place, individuals who have already lost so much.

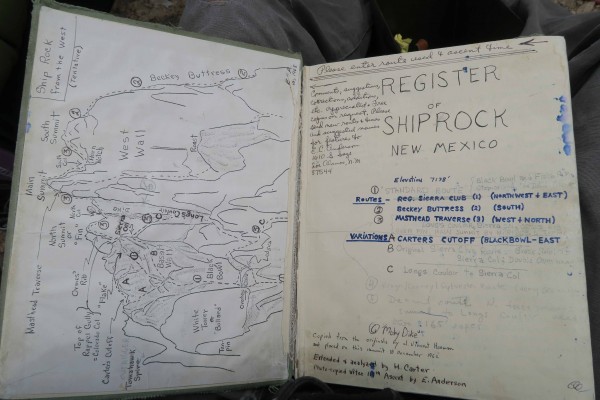

More recently I read about a Pat Goodman/John Sherman free climb up the formation. Hmmm. Then, this year, our travel plans would bring us from Moab to Santa Fe and on down to the Enchanted Tower: A path taking us very close to Shiprock. The itch grew a bit stronger, so I dug up an old 2002 trip report from Bill Wright that I had filed away for future reference. At the time I had only been climbing for a year. I re-read it, and gleaned some good beta, but their self-described “bandito” approach didn’t feel like the way I wanted to go about things. So, after a bit of searching, I ended up reaching out to a few members of the Diné (Navajo) Rock Climbers Coalition. Through our dialogue I found that we had much in common when it came to our attitude of climbing being a celebration rather than a desecration of these sacred places. Though their opinions are not necessarily representative of the Navajo Nation as a whole, I went forth with their blessing and made plans.

Photos, as beautiful as they are, do not adequately prepare the climber for the breath-taking magnificence of seeing Shiprock in person for the first time. Shiprock dominates the landscape from miles away, and approaching closer does little to demystify the hulking mountain. It is at once magnetic and terrifying. Robert Ormes wrote in 1939 “…its two summits…rise like the masts of a schooner riding full sail on the sea of haze which rolls over the desert horizon. Not until we drive around the west end of the mesa and come within twenty miles of the rock do the ethereal qualities begin to give way to solidity, and even when we come right up under it and wear our necks out with trying to grasp its tremendous height, some mystery remains. There is something unbelievable about a rock that could be set within the boundaries of a few city blocks, yet rises more than a third of a mile in height. In the evening you can see a shadow from it as long as Manhattan Island.” Indeed.

We arrived at Shiprock late in the afternoon. Satellite imagery shows several roads approaching the formation from all different sides. Google maps suggests approaching from the east but we followed the same path that Bill Wright and his crew took from the south. This is unequivocally the best approach: Service Rte 5010 follows the southern dike to the mountain itself along three miles of bumpy dirt road. With high clearance we were able to find a discreet place to park and camp for the night on the SW corner of the landform.

We took some time that evening to hike around the west side of the mountain to the start of the Original Route, below a massive amphitheater called the Black Bowl. From here we backtracked around a basalt tower called the Crow to a narrow gully that led to what we hoped was Long’s Couloir and the start of our route. We were uncertain but hopeful - that evening we slept quite well under the quiet shoulder of the rock.

We awoke early in the morning to intermittent sprinkles and grey skies. The weather wasn’t ideal, but we knew that Long’s Couloir could be rappelled so we decided to at least start up the route with the idea that we could retreat if necessary.

I cast off and quickly led the first pitch up a relatively solid, short ramp and into the bottom of the massive, steep, Long’s Couloir. We had picked the correct start and I quickly belayed Kate up. We then simul-climbed the next four pitches until we were dead-ended in a pleasant, boulder-strewn bowl tucked deep within the folds of the mountain. The climbing up to this point was generally solid, low 5th class with occasional steep steps up to 5.7 in difficulty. Most of this terrain is unprotectable but occasionally bolted anchors served as directionals to keep us on-route.

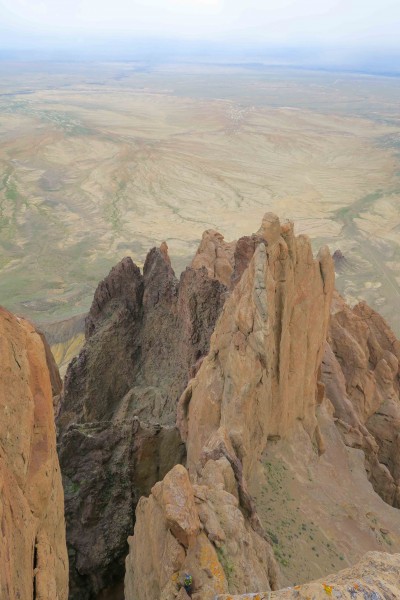

From the back of the bowl we looked up at the towering, unbroken, fluted curtains of rock that led up to the main summit of the mountain on the right, and the crazy, jagged basalt ridges of the Colorado and Sierra Cols on the left. In the center, on the back wall of this amphitheater, was the heart of our route: an undulating black dike ranging between 5 and 30 feet in width that snaked its way up the vertical wall several hundred feet to an unknown location high on the mountain. This was the Moby Dike and the crux of the route.

Our weather was holding, but we could see rain in distance to the west. Now or never! I launched up the first pitch - uncertain exactly where to climb - and found a terrible cam placement at about 40 feet. It would not hold a fall but I couldn’t stomach the sight of the rope running free from my harness all the way to Kate’s belay device. Another 20 feet and I found a rusted lost arrow off to the right. Clipping this I breathed a sigh of relief: Not because of the quality of the protection but rather to know that I was on route. From here I climbed another 10 or 15 feet and found the first bolt of the route. Locking carabiners were used.

Kate hid from the constant stream of flakes and rocks being knocked off by the slightest brush of my legs or the ropes themselves. The larger, more threatening rocks I would throw backwards away from the wall. Every hold was tapped. Weight was kept evenly divided between handholds and footholds no matter their size. The climbing was probably low 5.10 strictly speaking but 5.11 effort was expended.

Despite about a half-dozen bolts, a half-dozen knifeblades, and one or two gear placements, this pitch is very serious. It wandered off to the right, then back left, and sometimes there was mandatory pulling on, or standing on, loose or flexing holds. Solid holds were welcomed as rests no matter how small they were. About 120 feet out I reached an obvious ledge but there was only one bolt there. Could it be that Goodman and the Verm belayed off a single bolt? Supplemental gear was non-existant. For a long time I considered this but ultimately, despite rope drag and some of the loosest climbing on the pitch, continued on - traversing left from this stance and contuining upwards. At about 160 feet I pulled over a bulge and found two bolts - a belay!

Kate followed smoothly and slowly, but still probably in a fraction of the time my lead took. We agreed that the true crux of the climbing was not the difficulty of movement, but rather climbing without pulling off holds - which on lead could have terrible consequences. The rains had moved closer now - just a few miles to the west - and the skies were entirely grey. Bailing from this point would be relatively straight forward, but it wasn’t raining yet and I could see that there was only one more pitch of climbing to the saddle. Reasoning that I was halfway done with the business, I set off on the second pitch of dike climbing. This pitch immediately climbed up to and then around and over a hideous gargoyle of wedged loose flakes sticking straight out of a massive, decomposing groove. I was appalled that these blocks hadn't been trundled, but perhaps Tsé Bit'a'í, the great winged bird, was still alive and every so often new monstrous flakes would be pushed to the surface from deep within its body. In addition to constantly checking every foothold and handhold, I was now constantly monitoring the exact positions of both the lead line and the tag line in order to keep them from knocking off rocks. While before Kate was belaying from relatively horizontal ground and could move out of the way, now she was trapped at a bolted stance. In short order, however, a significant traverse leftwards brought me over very exposed terrain and then, ultimately, up to a belay off a bolt with a keyhole hanger and a loose angle.

The weather was almost upon us. Adding to this concern, due to the previous pitch's traverse and the undercut nature of the wall, retreat from this position would be unexpectedly difficult if not impossible. We could tie our two ropes together and single line rappel down to the bowl atop Long’s Couloir, but then we’d have to down-solo the first five pitches. I didn’t think a standard double rope rappel would reach anything but empty space and traversing back across the route would be very difficult.

By the time Kate arrived the rain had started and I was a bit worked up. Despite being only about 30’ from the saddle separating the north and main summits of Shiprock, I was concerned about our exposed position on the upper reaches of this complicated and mysterious mountain. Feeling rather alone, I wondered if my seemingly calm partner felt confident in our ability or simply didn't fully grasp just the committed position we were in. Fortunately, the decision of what to do was easy: The fastest way down would be up.

A little more loose rock led to the saddle - we left the dike behind now in favor of the tuff breccia so it was a welcome change in consistency of looseness: From large blocks and flakes to gravelly and crumbly. The saddle, if possible, raised the intimidation level even further. There was instant, mind-bending exposure. I couldn't believe it was possible to have climbed to the point I now stood, let alone to continue on. Huge, bottomless drops were all around and there was no relief in sight. I was a hundred feet or so above the top of the Honeycomb Chimney - a cavernous gully system that dominates the east face of Shiprock from ground to summit. I believe one rappels down into this chimney during an ascent of the Original Route, then traverses across the top of it, before ultimately continuing on to the summit. I could now see that I was only a few hundred vertical feet from that summit, but had no idea what the terrain would be like. Rather than climbing the ridge-like saddle itself, I traversed left around to the east side of the mountain and onto exposed terrain. Here the climbing continued to be loose and difficult, and concerned about protecting this traverse for my partner I continually back-cleaned (in hopes of eventually having a better top rope for her) each of the rusty pins that I clipped along the way. If I fell, as long as the lone pin that I was clipped into at any given point held, I would be fine. If not, it would be very bad. At a weakness I finally pulled back onto the ridge/saddle itself and was glad to have escaped without incident, but lamented that all my efforts to provide a better rope line for Kate were in vain: The geometry of the traverse just didn’t allow for a safe passage for follower or leader. I quickly wrapped the lead line around a massive boulder at the south end of the ridge, tied a knot, and put Kate on belay.

The skies continued to spit rain, and as Kate began to climb I silently willed her to climb faster to the nylon-amplified sound of rain drops hitting the hood of my jacket.

Kate not only climbed quickly, but also arrived at the belay smiling. For some reason she liked that pitch! The rain was intermittent, and we were close, so I took off on lead again. This time I was psyched - I actually had the opportunity to use all the trad gear I’d brought up on this climb. This final pitch climbed loose cracks up the steep southeast wall of the main summit. The rock was crappy but I knew my jams wouldn’t spontaneously explode out of the wall like the face holds lower down were prone to doing. I enjoyed the feeling of being able to pull harder rather than delicately and I grunted and thrutched my way up this pitch with great speed.

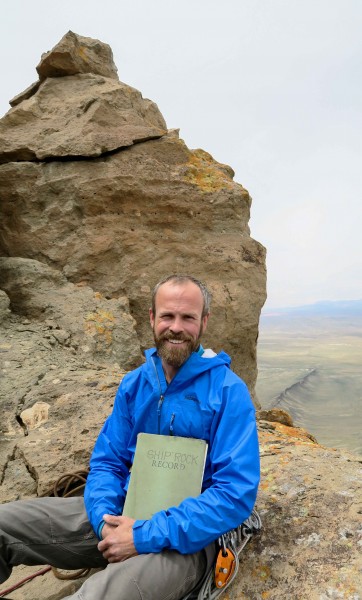

From an alcove tucked behind a boulder, I hip-belayed Kate up this pitch; ironically, this was the only pitch on which she struggled. But despite continually threatening skies, the rain had momentarily stopped. I led a short pitch up a slab and around some boulders to another flat spot just below the true summit. From here we took turns climbing up to the tiny, exposed spire summit of Shiprock - feeling awkward, stiff, and nervous unlike the many ravens and raptors that have undoubtedly found their way more gracefully to the same perch.

Unfortunately the weather prevented us from relaxing and enjoying the summit at length (perhaps my only regret from this adventure) so after some obligatory photos we both finally gave in to the sentiment that we’d silently been holding the entire day: Let’s get the f*#k out of here.

A few double rope rappels led back down into Long’s Couloir, the sun came out, and we had lunch before continuing down to the base via a few more rappels.

The route is Moby Dike, 5.10+ R, 1200’, ~10 pitches. Put up by Pat Goodman and John Sherman in March 1999. I recommend 1x 0.3 and 0.4 Camalots, 2x 0.5 through #2 Camalots, no wires, many long slings (essential!), double ropes (not a lead line and a tag line!), and helmets. We climbed the route in 5:30 car-to-car, but I consider this a good time and I would allow a full day. Retreat would be possible from the top of the first dike pitch; after that it would be more difficult. Pat rated this route 5.10+ R, but I would say it is more like 5.10- X: I feel that I had to call upon all 15 years of my desert climbing experience to climb this route without serious consequences. The reward, according to Pat, is that we are amongst a very small few who have truly "free climbed" to the summit of Shiprock. Thanks to Bill Wright for the inspiration, the Diné Rock Climbers Coalition (specifically Quentin Tutt and Alex Pina) for the encouragement and for teaching me about their wonderful people and places, Pat Goodman and John Sherman for sharing their kick ass route, and Kate for her partnership.