After Pear Lake at mile six, there are no signs of humanity for forty miles until Kearsarge Pass, from which highway 395 can be faintly seen, impossibly far, its distance compounded by the absurdity that its warm, black asphalt should conduct cars when the medium under the skier's foot is the windswept sastrugi of the Sierra's highest passes.

Unlike the famous Haute Route from Chamonix to Zermatt, this

forty-mile Californian ski tour has no huts. I've used European and Canadian huts many times, but---although it is undeniably magical to check into one right off a glacier and to drink wine with a four course meal ferried by helicopter from valleys far below---it is also hard to resist the wilderness of the Sierra. Ski touring has experienced double-digit growth in the states for years, but in winter and spring, near the geographical center of the most populous state in America, a skier will find no other people.

Rock climbing sounded stupid to me in high school. My physics textbook had a picture of some guy climbing a sandstone chimney, and I was supposed to figure out how he could rest in equilibrium so he wouldn't fall and die. Not for the first time in my physics class I asked myself, "why?" Finding some tenuous rest in a hole in a cliff where getting tired meant injury or worse seemed as contrived as lobbing water balloons at monkeys in free-fall. That guy's stupid and rock climbing is stupid, I thought. I guess I'm as dumb as the guy in the picture now.

At the end of the same year in high school I saw a picture of a place---of a type of place---that I had no idea existed on earth. It was of Denali from the tundra, and the enormity, impenetrability, and beauty of it awed me. I was on the phone with a friend and I remember telling her, "I just saw this amazing thing. I have no idea where it is. I'm sending you the link." She looked and said, "yeah, that's Alaska." Seeing that picture was like realizing I could sleep in a hotel on the moon or hop on the interstellar metro to the next star system; I couldn't believe that such an incredible place was within arm's reach---what's more, in my own country! I don't know why that picture affected me so profoundly and why the one of that beautiful, red chimney---probably one of Epinephrine's, now that I think about it---didn't. I don't know why it didn't affect my friend the same way. But it was the first time that a picture gave me such a powerful yearning to go somewhere. It's what started me in mountaineering, which is what starting me in climbing.

The second time a picture affected me the same way was when I stumbled across a picture on Google Earth of a snowy cirque in the Sierra Nevada. It was taken in winter and the cirque seemed to hang in the blue Sierra sky like some divine being's throne. There was no peak behind it to block the sky, so the world seemed to stop at the gentle ridge line, and it felt impossible that there should be anything beyond it. Seeing that picture of Deadman Canyon was another Denali experience for me. Is this really in California? I thought. That picture was the reason I learned to ski. I wanted to go there.

The process of learning to ski is easy enough in Southern California, but getting a touring setup, at least back in 2010, was frustrating. I bought a pair of skis, naively trusted Sport Chalet to mount them with Dynafits, haggled with management for reimbursement when they destroyed my skis, and ended up buying a pair of pre-drilled skis and mounting them myself. Learning at the resort was the way to go---after a couple of months of that I felt ready to hit some easy backcountry slopes. When a wild storm that dumped five feet of snow on Baldy abated I put skins on for the first time. I kept popping out of my bindings while touring that day because I didn't know the toe levers must be cranked so hard; every time I popped out I lost balance and toppled over, and I could only get back on my skis after grabbing my partner's leg. I thrashed my way into buried yucca once.

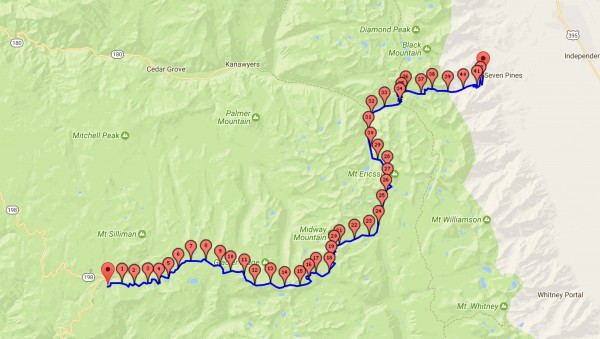

The route begins in Wolverton near Lodgepole among Giant Sequoias, and it climbs slowly, almost imperceptibly, along the gentle western slope of the Sierra Nevada towards the crest of the range in the east. The route ends where you want: some parties finish by skiing past Whitney, some by crossing Shepherd Pass, and others by dropping into Onion Valley. Some ways are longer, some shorter, but they are all more than forty miles long. The trouble with this trip is that, unlike in the Alps where you can hop on a train to return to your starting point, the Sierra High Route deposits you on the other side of a range so long and rugged that the easiest way to return to your starting point is to drive eight hours clear around it. One solution is to stash a car on the east side, drive all the way around the southern tip of the Sierra for eight hours to Wolverton to start the traverse, then drive again to Wolverton afterwards to pick up the other car before driving home to LA. Sixteen hours of driving! That would be a problem for us because we had no more than two days for the trip. Luckily another solution worked out for us: a couple of our French friends, Thomas and Clément, heard about this awesome traverse and wanted to do it in the opposite direction.

My partner on this adventure was Nick Stadie. He contracted mono three weeks before we were supposed to leave so I initially wrote him off for the trip because people take months to recover from that. A week before departure he said he would be strong enough in time, but I was still skeptical; I'd seen people with mono and they were less energetic than zombies. I figured he'd just ski back to the car to wait for Thomas and Clément if he couldn't hack it. But if I'd known Nick better I'd have taken him at his word: he is more robust than the sturdy mammals of his Canadian homeland, and not only did he recover from mono with superhuman speed and finish the traverse with me in two days, but he went on to place second in his first marathon ever later that year.

Nick and I gave my car's wireless door-opener to the French team and told them where to find the actual key in the car. They gave us their spare and set out on April 13, 2011, to ski in the opposite direction. They would start in Onion Valley and end in Wolverton four days later, and we would try to do the reverse in two days. Nick and I set out Friday night and arrived at Wolverton around 1 am, where we simply threw our bags on the ground and slept next to the car under a moon so bright it was hard to believe it wasn't already dawn every time I woke up. Dawn came soon enough, though, and we packed our bags for the day's stroll to Milestone Peak, over twenty miles away. My packing strategy on this trip was simple: carry as close to nothing as possible. I took a twenty ounce summer sleeping bag, a big down jacket, a three-quarter length pad, a Jetboil to melt snow, the clothes on my back, some repair tools, skiing gear, a hybrid pole-axe, a GPS unit, two days of food, a 3L water bladder, and a headlamp. That's it. My pack was 30L in size. We were confident enough in size of the snowpack, which was 180% of normal in the Southern Sierra, that we set out with only ski boots for our feet. We'll drive home barefoot, we thought! We even could have done without our headlamps, since it was bright enough to ski under the moon without them. My pack weighed thirteen pounds when my skis were on my feet.

We left the car around 7 am. It was my first time skiing on the west side, so it was weird to tour past Giant Sequoias instead of the usual cacti and sagebrush of the east side. In an hour, as we crested The Hump, the terrain opened up and we saw our first glimpse of the high country. It was the first hint of the vast, untouched fields of white I saw in that picture so many years ago. We took off our skins and did a short descent to start the traverse to the Pear Lake Hut, which was not trivially found. I skied down a creek until I found it, and the generous folks staying there offered me some of their already-filtered water before we set off into the remote interior of the range.

The sun was merciless midday, so Nick swapped his shorts for pants despite the oppressive heat. We skied through the Tablelands above the Pear Lake Hut, and as we neared the first major pass of our journey I started to wonder if the heat had really thrown me over the edge: were those

bear tracks over there? At 11,000 ft in April? I asked Nick and he seemed to see them too. We followed them as they headed up to Pterodactyl Pass. From there we could see the Kaweahs, a subrange so remote that most winters no one walks there at all.

We ran out of water just before Horn Col but lucked across water dribbling down a sun-baked slab near Horn Peak. We refilled without making a full brew stop. When we finally reached the pass around 2 pm the scale of our day's objective came suddenly into focus: Deadman Cirque was

enormous! We still had Cloud Canyon and two more valleys to cross before bed.

As we crossed Deadman Canyon we stayed high on the right side near the cliff bands to avoid losing elevation. The view to the west from the next pass revealed our folly: had we dropped just a hundred feet in elevation we would have saved nearly an hour of skinning across wet slide debris and contouring around rock buttresses. The only crappy snow of the entire trip but just below this pass. Everything else was corn---almost as skiable as groomers---except the hundred-foot stretch of waist-deep, thirty-degree mush guarding Copper Mine Pass. I joked nervously to Nick about about wet slides as I sank to my chest. After this formidable obstacle and a little celebratory Toblerone chunk above, we skied towards Triple Divide Peak as the sun began to set. Normally when that happens climbers freak out and take huge hits to morale, but something about the windless calm and the serenity of the deep backcountry kept us going. When the sun set and lit wispy little clouds with delicate pinks, I was reminded of how lucky we are to live near this gentle, beautiful place.

We reached Triple Divide Pass just after sunset. It was no colder than twenty-five fahrenheit and I continued in just two layers. I took off from the pass just ahead of Nick towards the low point before the next pass, moon-drenched, sparkling snow blurring past and freezing my face into a childish grin. On the frozen lake at the low point I turned around to watch Nick, his headlamp arcing in tight curves across a silvery mountainside, back and forth, back and forth, under a sky so choked with light that I wondered if Muir coined his phrase---The Range of Light---on a full moon's eve in winter.

We reached Lost Pass within the hour and skied carefully down the backside since it looked on Google Earth like the steepest part of the traverse. Our energy declined at this point and we stopped for bed half an hour before Milestone Pass. We had intended to cross that pass before camping, so the premature stop meant skiing extra-fast to catch some friends---unrelated to the Frenchmen---who would be on the way down from Tyndall the next morning. The mountains cradled us softly that night, the breeze nothing more than warm whispers from the decades-old, weathered books hidden in the craggy heights around us.

Nick woke me up at 6 am and we began skiing quickly towards Milestone Pass. Ski crampons were instrumental there. I arrived first and I was a little bewildered with what I saw: I thought there was supposed to be a pass there! Instead I saw a two-hundred foot cliff. After some discussion we decided that we needed to travel towards Milestone Peak along the ridge, above the actual saddle point, to a place where we could ski or walk down the other side. We scrambled through some rocky terrain, and on the way we noticed some movement on the other side of the pass. Could it be? The Frenchmen! They reached the pass just before us, where we shared wonder at our luck in having met at the literal high point of our trip. We could have swapped our keys there, we joked! Nick and I still had a long way to go to catch our friends at Shepherd Pass, so we bid them adieu and skied on.

This descent was fantastic. Whatever hesitation I might have had the previous night when I bombed down from Triple Divide Pass I let go in the sunshine of a bluebird spring's day; I must have hit 50mph as I skied from Milestone Pass towards the headwaters of the Kern. More childish grins. Around Caltech Peak we started to worry about the time and started to skate towards Shepherd Pass. When I got to within two miles of it I began to see little descending black dots on the flanks of Tyndall. I broke into a skiing jog. One little black dot passed over the horizon. I skied faster. Another little black dot disappeared, and then another. Soon there was only one black dot left, and having forgotten that I could simply catch them on the other side if all the black dots disappeared over the horizon, since they weren't skiing, I sprinted, wheezing on the 12,000 foot air. I arrived at Shepherd Pass before the last black dot, who turned out to be a complete stranger. "Do you know Pratyush or Patrick?" Yes, he did. He was tagging along on their trip---his first mountaineering trip ever. "Where did you come from?" I pointed and said, "a trailhead to the west."

We skied down to our friends at Anvil Camp along a narrow ribbon of snow that weaved among the moraines. We didn't hang around Anvil too long: we continued down, where we met a couple of other skiers around Stupid Saddle, the little 500 ft bump one must cross to get into the Symmes Creek valley. Due to a misunderstanding we decided we needed to take the donkey trail fork instead of the normal one, and we ended up walking for an extra mile and a half down the pack animal trail, well into the sagebrush and cacti of the Owens Valley. We hitched a ride to the van at Onion Valley around 7 pm, our tour complete, and regrettable though it was that Still Life Cafe was closed when we rolled into Independence, we went home knowing that we had just been on one of our most awesome trips ever.

Moral of the story? Get a pair of skis. Spend a year learning, then go ski in the Sierra! And most importantly: if you're going to do the High Route and you live in Los Angeles, email me and I will happily ski in the opposite direction. May next year's snowpack be less pitiful!