It was like any other start to a day of climbing in the Black Canyon. Dave and I are up before the sun, throwing down coffee and a quick breakfast, and assembling all the hardware needed for the day’s climb.

We gently descend down the Cruise Gully, careful not to dislodge any loose rocks, with thoughts that some climbers could be below us. Though our start was early, so early it seemed we might be the first people awake on the planet, we heard other climbers clinking-and-clankering around in camp before us.

Setting up the first rappel we hear a group just behind us. We both reach the base of the climb near the same time. The sun has finally risen, and we look up to 1,600 feet of granite above us. Looking down is the Gunnison River, frothy and green.

We strike up a friendly conversation with the other group of climbers. One of them is from Durango, Colorado, where I am about to move to from Gunnison. The duo seems to be eager to get on the wall, so we agree to let them go first, as the climb we are about to do shares the first pitch with theirs.

The climb, The Cruise, is going fantastically well. We end up climbing a little faster than the other party, and are ahead of them when the two climbs intersect again. The pace and progress is extremely satisfying. Many years ago I had done the climb with my friend Gene, and got stuck on the wall overnight, without any sleeping gear, and spent what seemed like an eternity waiting for the sun to rise, shivering in the depths of the deep, dark Black Canyon.

At the belay ledge where the climbs came back together (the Scenic Cruise is a 2-3 pitch variation to the original Cruise route) I start talking with the other party. The guy from Durango, who is leading every pitch, is friendly, so we talk it up while belaying. I start to pick his brain about his favorite climbs in the Black, and he mentions The Southern Arête on the Painted Wall, with an incredible finger and hand crack way up high on the main face. Soon it’s time to climb again as we progress up the wall.

The rest of The Cruise is a cruise, and we top out before the sun goes down, heading straight back to the campground to chug Gatorade, eat some food, and eventually have the celebratory beer. The feeling after climbing that much rock is intoxicating, a high of a day well spent in the vertical with a good friend.

Dave and I are beyond good friends though, we are climbing partners for life. Ten years of climbing adventures have solidified our partnership and friendship, and The Cruise is one of the longer routes we have done together. In climbing, when you’re young and you’ve got a solid partner to climb another day with, the feeling of success always leads to the inevitable conversation of what route is next?

In the safety of the horizontal, talk turns to the next climb in the Black. We mention several routes, and I bring up the Painted Wall. Neither of us has climbed the wall, the tallest cliff in Colorado.

Since I am about to move away from Gunnison, I think that climbing the Painted Wall would be a good way to commemorate the eleven years I spent there. Dave seems keen on the idea, and we make plans to return to the almighty Black Canyon.

The three weeks after we climbed The Cruise are a blur. Since I recently quit my job, I’m unemployed with very little responsibility. I slack off at home, drinking too much beer, eating too much ice cream, and watching too much television. When Dave and I reconnect and plan to climb the Painted Wall, I am not only excited to do the route, my body and soul need to climb.

I gather as much information as possible about the Southern Arete, mostly through my friends that have done the route. I try to stay away from internet forums; the Black scares many a climber away, and reading about some stranger’s horrific experience on the route just might taint my image of the climb.

All of my friends report that the route is long, very long, when you think you’re at the top, you probably still have a ways to go. The hike back is also an endeavor in itself, and a couple of my friends tell me stories about wandering around the rim of the canyon in the dark, stumbling for hours without food or water.

Dave and I decide to meet up in the afternoon the day before the climb and scope out the trail to the top of the Painted Wall. We stash a jug of water; in the Black one almost always runs out of water on the climb.

The night before the climb I am tired, but wired. I eventually fall into a restless sleep, my internal clock just waiting for the annoying alarm on my cell phone to go off at four thirty, and I wake up several times in the night thinking it is time to wake up.

Breakfast, coffee, it’s all hurried like always. I feel like I haven’t really slept. It’s a colder morning than when we did The Cruise. It’s October now, and the cool Colorado air seeps into our bodies and under our skin.

We begin hiking down the S.O.B. gully, stepping down boulder after boulder, descending into the canyon. After an hour the sun is up, and the Painted Wall is before us: proud, provoking fear but at the same time encouraging courage. Large pink pegmatite bands run through the wall, like brushstrokes from Mother Nature. Some of the peg bands explode like lightening across the wall. Other sections of peg, near the top of the formation are seventy to eighty feet tall and hundreds of feet across. The larger peg bands near the top of the wall are supposed to resemble dragons, and hard core Black Canyon climbers have horrific tales of climbing these features.

All around us are other big walls, granite everywhere in every direction. The Gunnison River rages through the canyon, small waterfalls produce frothy whitewater, as the water flows past boulders that fell of the canyon walls many moons ago; all this wild rock scenery with no other climbers in sight.

Some walls are better to look at than to climb. The closer we get to the Painted Wall, the uglier it appears. In the Black Canyon guidebook, it is described as an “overhanging scree field.” In the last ten years I’ve been climbing in the canyon it is the only wall I’ve regularly heard about sections of climbs falling off the wall. Yes, that’s right, a pitch of the climb literally coming undone from the wall, adding to the scree fields below.

From afar it is a masterpiece, up close the loose rock and questionable features are more visible; any climber that does more than one route on this wall is a true lover of the brutal, Black Canyon.

We slam water on the approach and fill up our water bottles in the river, adding iodine tablets for purification, near the beach-like camp sites that brave fisherman and even braver whitewater kayakers use. For some reason we linger at the river, as if we had the time to. Finally, we make the last approach to the start of the climb.

After hearing stories of friends getting off route on the start of the climb, we’ve carefully studied the initial section from photographs, and various overlooks in the canyon. Dave sets off leading, and eventually the rope comes tight, and it’s time for me to start up. The first pitches are the type of climbing one would only do to attain better terrain up higher: loose blocks, prickly bushes, and funky cracks. This leads us up to a scree field and finally some better climbing. Eventually we’re as hot as we were cold in the morning, and we strip layers off as if they were useless, tying the clothing off around our waists and stuffing it in our one, small back pack.

The climbing gets better, nicer cracks, and a bit less loose rock, yet we’re amazed by the choss of the route, given how many times the route had been climbed. I take note that even Dave, an alpine climber, who has seen his fair share of choss, makes multiple remarks about how loose the climb is.

We’re enjoying ourselves, slowly progressing up the wall, and into a long chimney/off-width system. The chimneys demand complete focus and concentration, as the protection is sparse. Forty feet of chimney climbing without gear is common, and we wiggle ourselves in to the cracks, facing the fear of the situation.

The climb has been full of booty, gear left behind from a party that had to retreat; I take the time to remove some of the gear, mostly nuts, slings and carabineers. There isn’t a bolt or a fixed anchor anywhere on this route; typical style of a Black Canyon climb. It’s a style I’m grateful that the pioneers of the canyon established, one that forces the climber to be creative with gear, and rise to the occasion of the occasional runout.

The chimney pitches go on and on, and I feel that feeling of dread that many, including myself have felt before in the Black Canyon, “Are we moving fast enough?”

After leading a block of pitches we are finally out of the chimney system. When Dave reaches my perch, a comfortable-sized ledge, I glance at the watch he’s got on his harness, it’s getting late, and it’s time to get off this damn wall.

Dave takes a quick glance at the topo, and leads off into a run-out 5.9 face section, completing the dangerous section quickly. Then he takes a wrong turn, heading left into no man’s land. He realizes he’s going the wrong way, and finds some slings wrapped around a boulder, following in the footsteps of another climber that has made this mistake. He quickly lowers off this anchor back to my ledge, and pulls the rope.

The feeling of dread hits me again, “We’ve got to get out of here man.” We study the topo and realize we need to get out on the main face of the wall, and go right instead of left, realizing that Dave was headed the correct way, but needed to traverse right where he went left. The face section has no protection, and is right above a massive boulder, above a chimney gash that we can’t see the end of. A fall would be disastrous. I’m tired and mentally drained, and I can’t complete the moves.

We study the topo and the wall again. By this time the sun is setting and we can tell it won’t be long before the light is leaving us. We are perplexed by the wall, and what we should do. We know we need to climb, but can’t figure out which way to go. As the sun keeps setting more dread comes over us; we’re about to be stuck on the wall without bivy gear for the night.

“You’ve got that lighter right?” I ask Dave.

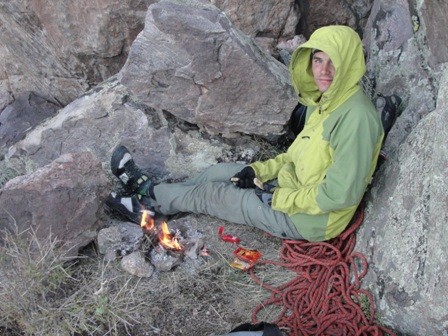

Immediately, I begin a scour of the ledge for meager pieces of twigs and branches from the prickle and Mormon Tea bushes, assembling a humble pile. We pick out where we are going to sleep, there’s a small section where we can both lie down in the fetal position, with small rocks built around it, evidence that other climbers have been in our situation before, stuck on the 2,300 foot Painted Wall for an unplanned bivouac.

The dread overcomes us for about an hour till we sink into the despair of the situation. Then it’s not so bad; it’s a waiting game, we have jackets and hats and gloves and layers, and some twigs to burn so we probably won’t become hypothermic. Most importantly, we are in good company. Dave and I have spent several nights together in the vertical world.

Conversation is minimal, but Dave and I both stay positive. At one point he tells me, “Well if there was anyone I would want to be benighted here with it would be you.” Dave is an accomplished climber, and I take the comment to heart. Neither of us blames the other for the grim night we have ahead of us.

The night sky is clear, another positive sign we’ll be fine on the wall. We watch the stars as if they were the big screen. Slowly they appear in the night. Soon the sky is an expansive array of the stars. Dave points out some constellations I’d never seen before, but I have forgotten, and will forget until I see them again another starry night, and then remember.

The stars change as we watch them; they represent the only light in the sky, save for the occasional airplane, the new moon is barely even a sliver. We curl up, spooning together to make vain attempts at sleep. The sleep is not real sleep, but the mind starts to dream for a second, until it realizes that the only dreams that will be had that night are the lucid dreams of staring at the stars, and realizing that you are cold and stuck on this wall.

I keep pestering Dave to burn some of the twigs for warmth, probably once every half an hour. At two in the morning he gives in. His reluctance to start burning the small branches was smart, they last till the first rays of the morning sun come from over the rim of the canyon.

We eat “breakfast,” what’s left over from our food stash: a gel for me and a granola bar for Dave, no water to wash it down.

We wait for the sun to hit us, to warm us up. Eventually it does and we start staring up at the wall, looking to unlock the sequence of where to go. We’re both dehydrated and fatigued. All we want to do is get off the wall. Going down isn’t an option, we’d lose half our rack if we decided to rappel.

After staring at the granite wall as if it were a chess board, and trying to decide our next move, I make the decision to try a different way than the topo from the guidebook suggests: a traversing section, which looks like there are some cracks for gear, unlike the runout section the guide describes.

The feeling as I start leading out is more dread and fear, but the motion of climbing on with risk is not as bad as the initial dread. I place some gear and traverse out, looking up on the wall for the finger and hand crack that is supposed to be the finest climbing on the route. My heart pumping, my muscles feeling the burn of the night without sleep and water, I move delicately on decent, but lichen covered holds, every move a prayer that the climb will continue without a fall.

Eventually, I secure more good gear in the grassy cracks, and I spot the beautiful finger and hand crack above. I build a belay and bring Dave up. We manage the crux pitch, exhausted, pulling on gear for progress; whatever it takes. The rest of the climb wanders up loose sections of granite, with more loose blocks everywhere; when we think we’re at the top, we’re not there till finally when we look back at the South Rim and we’re even with it.

A final section of moderate cracks through the pink pegmatite and we are at the rim, done with the climbing. Dave, appearing exhausted but relieved, gives me a big hug, and a weight is carried off my shoulders. Finally, in a rush of endorphins, the suffering on the wall is rewarded. A wave of relief and happiness overcomes me.

We wander through the woods to find the hiking trail that will lead us to camp. Every step is a challenge, with no trail to guide or way we just wander, with Dave’s sense of direction guiding us. Ten minutes in I step on a cactus, and it latches onto my ankle. I scream out in pain, and then remove it. Five minutes later I step on another one.

Finally, we hit the trail, and after stumbling along the trail for twenty minutes we retrieve the stashed jug of Gatorade water. Dave gets it out of the tree, and insists I have the first sip. The sensation and taste is better than any drink I’d ever tasted in my life. We savor the half gallon, it goes quickly, but it was enough to snap us back to life as we continue on the trail. Just as the trail ends and the ranger station appears on the horizon so does Ryan, a climbing ranger, who is also a friend from Gunnison, about to set out on a jog to check up on us. We’re glad to see his face, and he shows us to the water spigot on the ranger’s station.

We hop in Dave’s truck to drive to our campsite to recover. The fruits of the world put us in a dreamlike state of satisfaction as we bask in being young and alive. First it’s the satisfaction of water, then food, then finally beer. We build a proper fire, and I’m so tired I start to hallucinate in the coals of the fire. Crawling in to my tent at the end of the evening, I feel like king to be in a sleeping bag.

The next morning the endorphin high, or adrenaline or whatever, is still present, a feeling of accomplishment and relief. The world is ours to be had. Dave and I discuss where we went wrong, wasting time here and there. In this moment of repose we can’t take back anything; we can only learn from the lessons and improve our efficiency with time. Besides we still felt as if we’d accomplished something, we climbed the biggest wall in Colorado. And isn’t the soul point of climbing how you feel while doing it, and afterwards in the celebration of it all?

That was the end of the Black Canyon season for us. But, the climbing season continued. I moved to Durango where the beginning of winter was exceptionally warm, until the snow finally came.

One day at East Animas, the local crag, I ran into Marques, the fellow from Durango we’d climbed alongside on The Cruise. He asked me if I made it back to the Black after that route. I replied that I had and we did end up doing the Southern Arête on his recommendation. He smiled and gave a look only a fellow climber could, who had climbed the route as well.

“It’s a long one isn’t it?” he said.

I thought for a second to go into the details of the climb, the benightment and all that, but decided not to. I simply replied, “It is a long one,” and my mind drifted off to the Black Canyon.

This piece will be published in "The Climbing Zine Volume 3" in the spring of 2011.

More of my writing can be found on my blog at:

http://lukemehall.blogspot.com