edited by Pete Zabrok

Mark:

BIMD – meaning Back In My Day – we believed the only way to climb big walls safely was to climb them quickly. Hammocks were cramped and uncomfortable to sleep in and their flies useless, the food was both cold and heavy, and our “bad weather clothes” consisted of wool and Chouinard Foambacks, which was a essentially a rain slicker lined with a thin layer of foam. A typical day started about the time the first sliver of light glinted on the horizon, and you were woken by the cold after a miserable night. You were so uncomfortable, you almost didn’t mind getting your ass in gear, if only to try and warm up. You wiggled out of your sleeping bag – if you were lucky enough to have one, though a down jacket and legs stuffed into your pack usually sufficed – then you gobbled some granola, gorp or Vienna sausages, stuffed your hammock away, got your rack assembled and then you took off on lead. If you were not on the sharp end by the time the sun hit the top of the crag, you were going too slowly. One to one hauling dictated that you brought only the minimum of food, water and gear, and often the slightest sign of bad weather forced you to retreat. You were always a bit hungry, always had an eye on the weather, and were always looking down, keeping aware of your position on the wall in case you chose to bail.

Visit on gorge.net

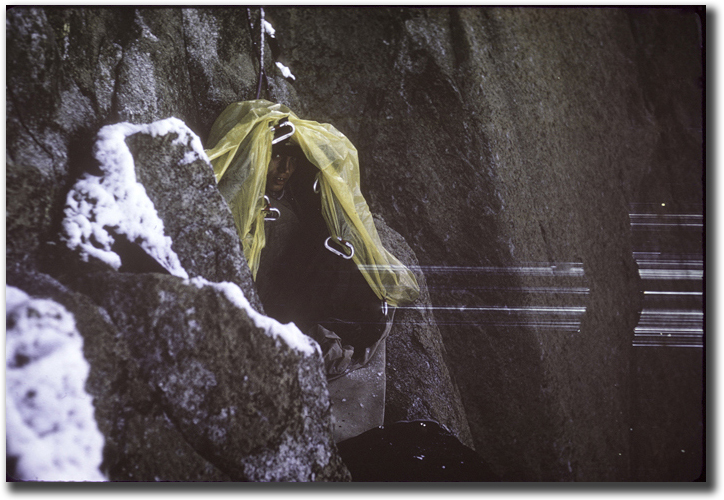

Bivy on the Magic Mushroom, Spring, 1977.

John:

Some adventures are cursed and others are blessed – with good luck, good weather, or good omens. On my first big wall, eleven years ago, I pulled up to the Meadow, lept out to gaze in awe at the looming Captain, and promptly locked the keys in the car. At the Great Roof, I dropped my grigri - in the dark. Topping out five punishing days later at sunset, my partner and I were afraid of sleeping on the summit with the bears (I swear we were!) so we spent all night hiking down the Falls Trail, barely able to locate it in snow and in standing water up past our ankles. I had to throw away my brand-new Five Tennies after just that one ascent

On my second attempt on the Nose, my partner and I climbed to Sickle with three ropes, ready to fix. Ominous clouds threatened. My partner - even less experienced than I - urged us to push on. I refused and we bailed. It rained day and night for the next 72 hours.

Last fall when attempting the Shield, I had walking pneumonia and we bailed below the Shield roof, where I was barely able to make upward progress without fainting

Then last spring, I had ropes fixed and bags ready to haul up Mescalito. My partner jugged thirty feet off the ground, said his shoulder hurt, and bailed.

This trip was different. Right from the start and only a half hour away from home, some sixth sense made me ask Mark if he had seen the ledge go into the van. We had been planning our gear list and packing our stuff for months. We’d reviewed the final list at least five times together. We both saw the whole pile of Mark’s gear get tossed into the van. Really I thought we had the ledge, but I’m a little anal retentive, so I asked, as casually as can be, “Hey, um, Mark - didja happen to see the ledge go in?”

He said, “I think so...” So we drove on a bit farther. If we hadn’t taken the full-on luxury-ocean-cruise kit of gear, I’m sure he would’ve added, “...you moron.” But past a certain gear load, the mind just cannot keep up

Visit on gorge.net

Do you see a ledge here?

With horror, it finally dawned on me that we might actually have left the ledge behind. I said, “I really think we should check.”

Mark looked at me and said , “No, we have it. Well, ah, maybe we don’t… And now that you mention it, maybe we’d better stop to check”.

We stopped and checked. No ledge

Was Mark’s wife surprised to see us pull back into his driveway, or what?

Video: We forgot the ledge.

Then, after having lost only an hour - god a’mighty I am so thankful it was only an hour! - to the retrieval of the ledge, we drove almost all the way to Yosemite. Had we not remembered in time, and had we later that night opened the back of the van to find no ledge, the phrase “It dawned on me with horror” would have taken on a whole new meaning.

After the close call with the ledge, we continued to skirt catastrophe, whether by force of will or by dumb luck I don’t know,. As we drove through the empty Oregon grasslands, the phone rang. A friend had to postpone a climb; that caused my carefully made pre-launch plans with other friends to fall through. People were going to be disappointed; the pressure was now on us to skimp on our wall time in order for me to fulfill my obligations. We frantically changed our campaign tactics; the cell phone rang again; we changed them yet again. We actually had a sheet of paper on which we wrote out our activities with each different pre-launch friend every day, to make sure that we didn’t accidentally short-change our Shield ascent. Finally, I called to cancel with my friends - the wall came first. As soon as I did it I was heartsick. I could hear the silence on the other end of the line. I was letting them down. Worse, I knew that bad juju is poison on a big wall.

Just as the ship seemed like it was foundering on the reefs, another call came in. A postponement turned into a cancellation. I could uncancel with my friends but - no cell service! I monitored my phone’s bars for what seemed like ever. A few tense hours later, I got through to them, heartfelt apologies were made, plans were changed one final time, and magically we stumbled into a super fun way to start a wall: the 4-day liftoff.

Mark:

When I first attempted the Shield in 1982 with Eric Barrett we started from the ground with one pitch fixed and none of the gear humped or hauled. Community fixed ropes down from Heart were not “de rigeur” in those days. Our plan was to climb and haul the Free Blast. I’m sure we planned for a four-day ascent, and we managed to climb to Gray Ledges that first day – pretty much halfway up El Cap – a total of 14 pitches led, hauled and cleaned. I had brought one of the original Gramicci portaledges, and Eric had a hammock. We had also both brought “reading” material – Me a Playboy, “just for the articles,” I claimed although Eric’s Penthouse offered him no similar pretext.

Visit on gorge.net

Mark Hudon and Eric Barrett on Gray Ledges in 1982.

We arrived at Gray Ledges that day in 1982 just in time to see a slow team head left up the first pitch of the Shield proper, rather than following the rightward Muir Wall traverse on the Triple Direct. They had climbed four pitches in the time it took us to climb fourteen. Since they were going so slowly we were sure they could only be a Triple Direct caliber team, for no Shield team could possibly take so long. Our plan had been to climb to somewhere low on the Shield, then to Chickenhead the next day, and off the next. We were feeling sort of beat the next day, but when the team above didn’t get out of their hammocks till one in the afternoon and then dropped a huge rock on us without any warning – which exploded only twenty feet away and cut our haul bag and my arm. The team ahead of us was tragically slow and we were both a bit freaked about the rock fall. We climbed one more pitch and bailed.

John:

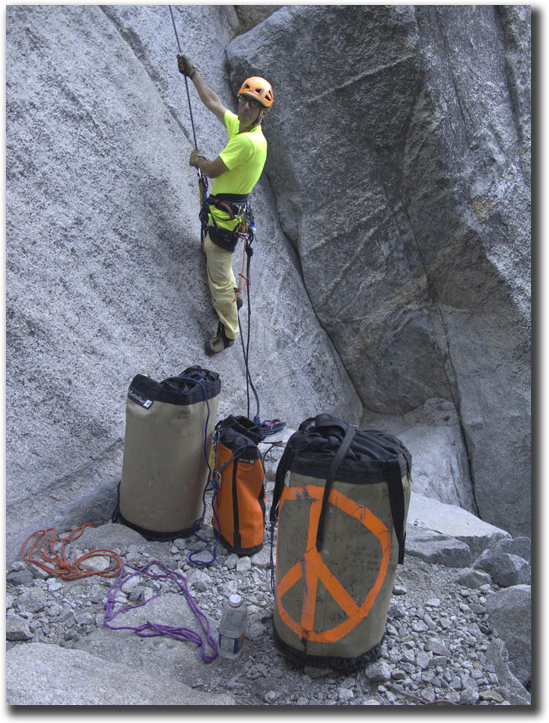

Back on the ground and in present day, our 4-Day Liftoff not only allowed us to hang with friends, but it was also calculated to avoid exhaustion. Our first attempt on the Shield the previous year - Ground to Gray in a day, fully loaded - was just too punishing. (I’m glad to know that even Mark found this to be true; I thought I was just a wuss!) I clearly remember on our previous attempt that dragging the pigs across Mammoth felt almost impossible; this time, in three parts over four days, a few easy steps got us there. Yes, that’s right, we jugged to Mammoth *THREE* times, taking one third of our load each time.. Unorthodox, but nice and easy. Our food went up in the last load to hopefully prevent it from being raided by wall rat, both the four- and two-legged variety.

Mark:

As you have been reading, my second attempt on the Shield came almost thirty years later in the fall of 2009 with John Fine, and we didn’t get much further than in 1982.. I was still living in the past, and believed that climbing fast was the way to go. In our 2009 attempt, John and I humped two loads each to the bottom of the fixed ropes, then we hauled to Mammoth, and then climbed and hauled to Gray Ledges before stopping, all on our first day. What the hell was I thinking?? Even so, I had been hoping to climb two pitches higher still and bivy where the Shield goes left and the Muir/Triple Direct goes right.

At some time during my vertical forced march, John began to complain about feeling weak and sick, but I tried to ignore him and kept pushing. I hadn’t been successful on an El Cap route in many years and I sure as hell wasn’t going down easily. The next day, when John called down from mid-point on lead that he needed to take a rest because he was dizzy, I pretty much figured our fate was sealed. After taking stock of John’s weakened condition, we really had no choice but to bail.

Video: Bailing from below the Roof in 2009

John:

When Mark and I first tried the Shield together in 2009, my body was sick and it made my mind weak. Belaying Mark on the pitch before the roof, after he went around the corner where I couldn't see him, I suddenly burst into tears. I always think of my family when I'm feeling bad on a wall. I was hanging there, blubbing out loud, "I love you mom <sob, sob>!" Jeezus, if you ever saw my mom and I together over the last forty years, you'd know that I was seriously messed up to be doing *that*. It’s lucky for Mark that he didn't have to watch.

Visit on gorge.net

That’ll work.

Then again, the next night, after making the bailage decision, we're sitting on our portaledge, both facing out, looking at the valley, drinking whiskey, lost in our own thoughts. Out of nowhere, Mark starts blubbing - full on as bad as I was the day before! "I-I-I'm sorry, I'm sorry", he sobs, "But I was feeling so good in my steps, I was feeling so good..."

Damn, what would Bridwell do in my shoes? I mean, this is Mark Hudon, and he's a *guy*, and I'm a *guy*, and we're sitting shoulder to shoulder, and he's *crying*. I did what seemed right: I put my arm around him, gave him an awkward manly hug, and said,"It's OK, it was my fault, I was sick. We'll get back here and send this thing".

Mark:

That night on Gray Ledges had been my first night on El Cap in years and I had thoroughly enjoyed it. I began to question why I needed to race up the cliff, why try to shorten the very experience that I longed for? That winter I decided to solo an El Cap route and while I was on it I was hit with the double whammy of “two pitches a day is as fast as you can climb and you’d better be happy with it”. It turned out that I was, and it changed my whole attitude. All of a sudden I saw that being on El Cap was the point of the game, not just racing to the top. Gear is now far better and lighter than BIMD, clothes are lighter and better, food, portaledges, flies, the whole nine yards, the game had changed. Back then we used to joke about how the best part of climbing El Cap was being in the bar telling stories about it afterwards. The feeling of being “at home” which I wrote about in my solo trip report is I think what we all go up there for. And those who don’t might well be missing out. The whole experience is so wild and strange, yet paradoxically so comfortable and comforting. The paradigm had changed, we could now take our time, enjoy the experience of hanging out on El Cap, maybe telling stories about drinking in a bar somewhere instead of rushing to the bar to tell the story.

Days later on our drive home, John and I discussed how we would take a more casual start next year when we came back, starting with getting some youngsters to haul our bags up to Mammoth for us.

John:

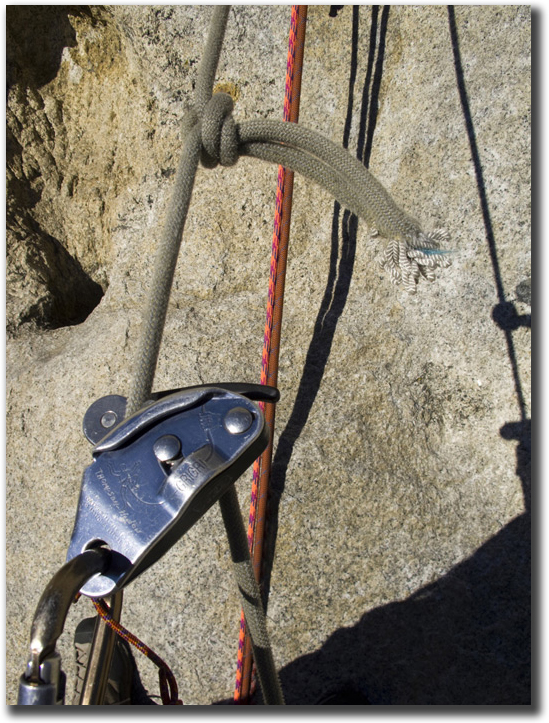

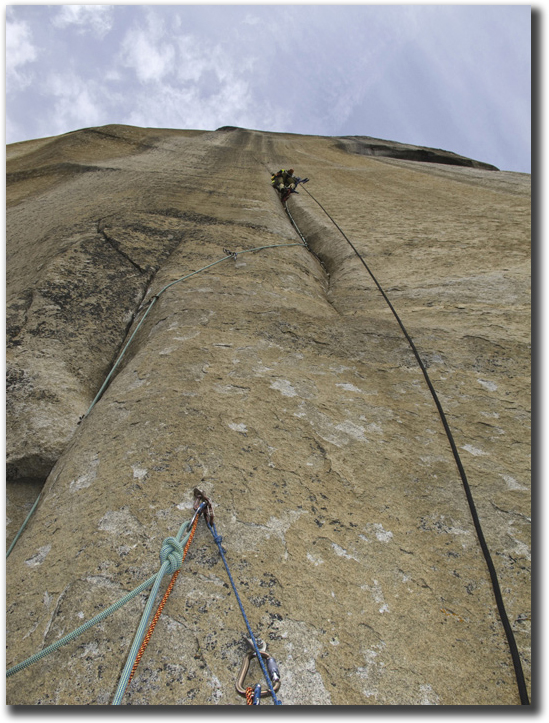

Well, we never did find those youngsters, so we ended up doing our own hauling, but at least we took it easy. We would take four hours at a time to shuttle “light” loads up the fixed ropes to Mammoth, over the course of three days, and then hang out with our buddies on the valley floor in between hauling trips. We were lucky once again; a fixed rope welcomed us at the ugly pitch between Heart and Mammoth, and Mark devised a cool “no brake, no pump” hauling method - just walk down the face till the bag jams the pulley. It turns out that one third of a big wall load is just the right weight to counter-balance Mark and me – both lightweight guys - on the low angle pitches up to Heart.

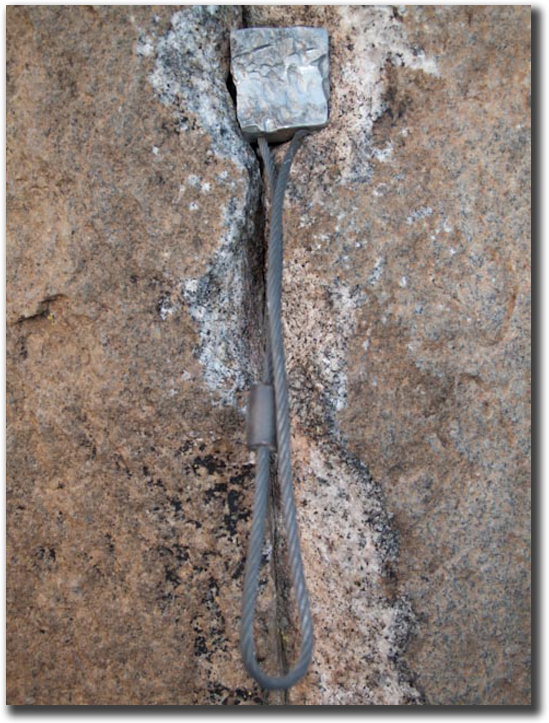

Visit on gorge.net

The pulley is a 36kn rescue pulley.

Relying only on the haul line for my life gave me the willies. After mounting the hauling pulley at the anchor and backing it up, at first I tried to back myself up on the fixed line. But Mark was using it to jug so that wasn’t going to work. Then I tried using only the grigri as a clamp on the haul line (backed up, of course!). My thought was that if I used my ascenders (which I needed for climbing back to the anchor after walking myself down as the load went up), a sudden jerk on the rope - like if my weight more than countered the load and I screamed down until the load hit the pulley, then suddenly stopped - might cause the ascenders to cut the line. But after Mark passed me by the first time, jugging up the fixed line as I was fumbling to re-attach my ascenders, and shot me a skeptical, “what are you doing?” look, I gave up and just went for it, figuring that I couldn’t take a real leader fall on a tight rope (I did use a biner through one ascender to ensure it couldn’t pop off the rope). The real truth was that I just sort of gave in to Mark’s more bare bones version of safety systems. We had to rely on the haul line not failing, and on the locker connecting the haul line to the pig not failing. But we had a fat haul line and a fat biner. Time to suck it up!

Video: Jugging and Hauling to Mammoth

Mark:

This fall, John and I again planned to climb the Shield. This time though we planned to haul a few loads up to Mammoth and then to not climb any more than four pitches a day, in fact, we figured that since the Shield headwall is such a unique place, we should spend as much time on it as possible. We planned to bivy above the Roof and then again above the Triple Cracks. We vowed to stop and set up camp regardless of the time of day.

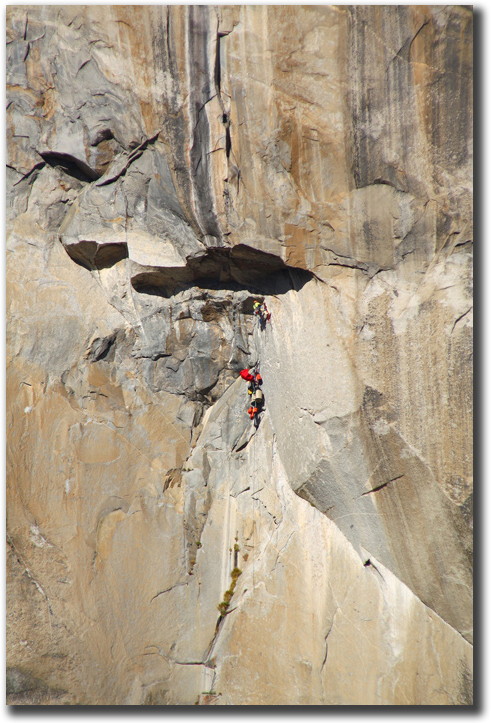

Visit on gorge.net

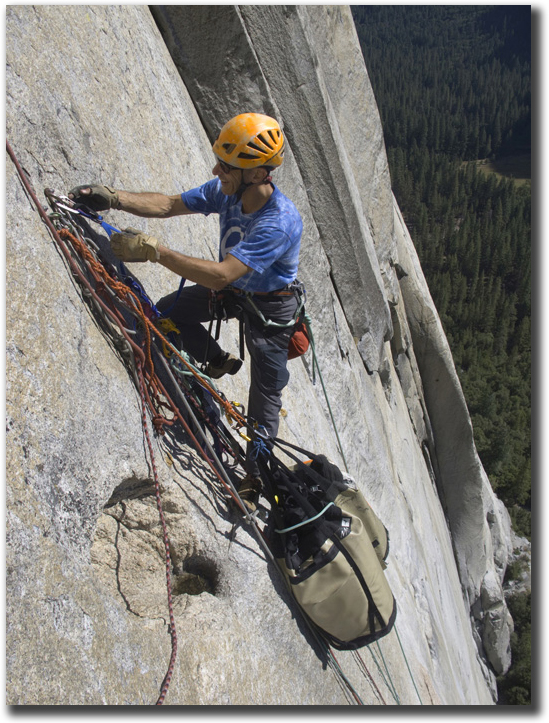

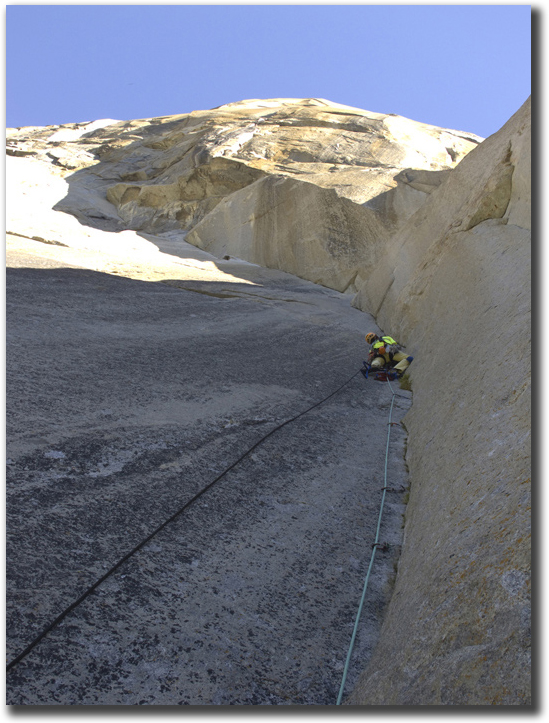

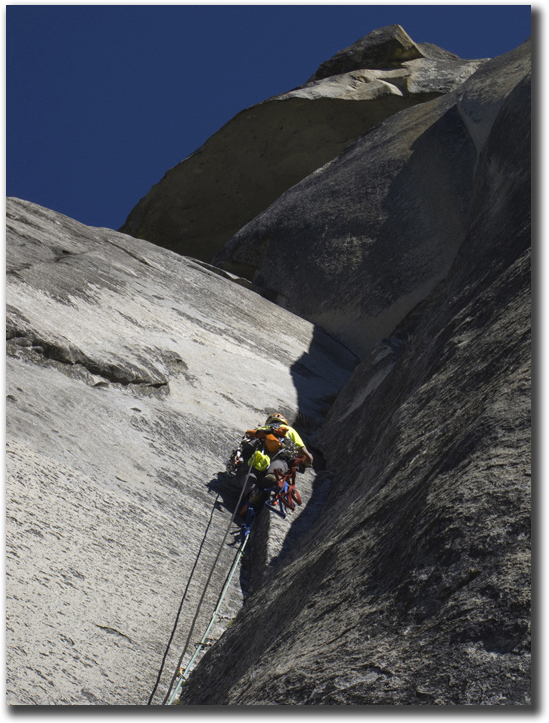

John on the Fixed Lines

October came and we drove to the Valley, and within an hour of arriving we were humping loads to the base. That first day we humped all the water plus some odds and ends, a total of probably a bit more than a hundred pounds.

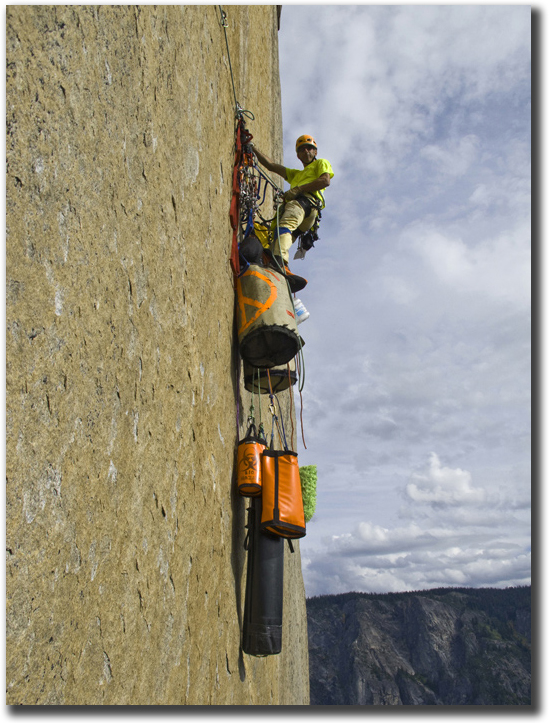

Our chosen method of hauling up the fixed ropes to the base of the Heart was to simply use a 2” sheave rescue pulley, back it up with a quickdraw, unclip from the anchor and run down the cliff till the bag hit the anchor and then jumar back up. No suffering, hardly any work and lots of fun. After our first day of hauling, we stashed our gear on Mammoth along with a note that we were coming back soon and this was not water left from a bail. We found dozens of half gallon water bottles all over Mammoth and later, when I led the pitch above, I found forty or so 1-liter bottles! All these water bottles are essentially litter and garbage. In the future, I’ll be emptying and carrying any unlabeled water bottles off the cliff.

Visit on gorge.net

Our water stash on Mammoth.

The next day we humped and hauled another load. Our part of the cliff was alive with activity – there were people on the ropes above us, people rapping down the ropes, a party sleeping on Heart and two parties starting up Freerider and the Salathe. Luckily for us, there was no one heading for the Shield.

John and I were actually having quite a good time hauling loads, we’ve climbed together a lot in the past two years and were really starting to understand each other’s “flow” on the rock. I had climbed a dozen El Cap routes before John ever tied into a rope, so I was the oldtimer, the grizzled veteran of El Cap routes back in the day before three bolt anchors, cams and even topos. John, on the other hand, had learned how to climb with quickdraws, 3/8 inch bolts and Grigris. In my humble opinion, a lot of new climbers these days are blinded by safety and by the system they’ve learned, and some can’t think out of the box. John suffered from this a little I thought and I went to lengths to explain to him how to be fast and efficient yet still be safe. I told him of how Max Jones and I had climbed Mescalito years ago and had not yelled a single climbing command during the whole route. I told him, “look, when I’ve been on the lead for a while and all of a sudden I pull up a bunch of lead rope and a few minutes later the haul line starts to get pulled up and then comes tight and starts to lift the haul bags, what do you think is happening? Do you think I’m up there climbing with the haul bag dangling from my waist? And if you figure out that I’m hauling, don’t you think that I’ve tied off the lead rope and it’s ready to jug? What else could be happening?”

John is a very analytical guy and I could see the gears turning in his head. We’re both technique geeks and we would discuss the best way to do something faster and easier at every opportunity. He began to get it and eventually it wasn’t more than ten or fifteen minutes after he had arrived at an anchor after completing his lead that the haul line would come tight and the bags start to move.

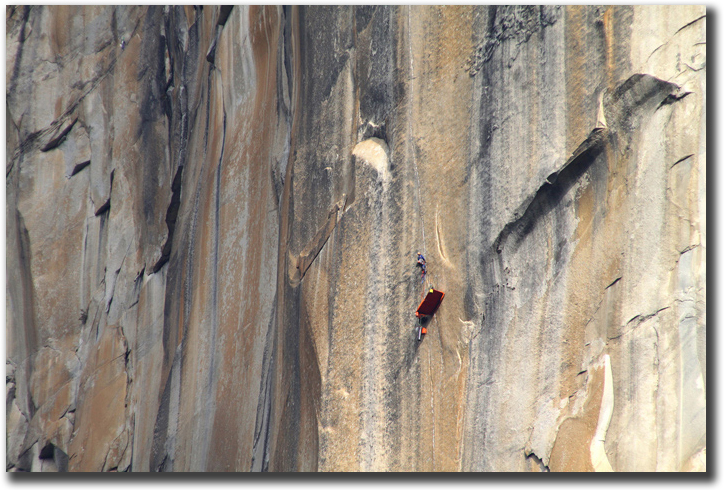

Visit on gorge.net

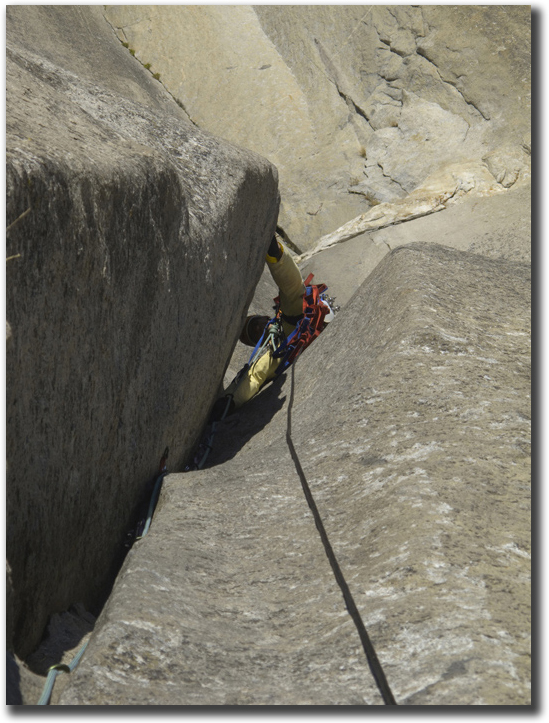

The route overhangs a bit right in here.

Big walls are hard enough that every opportunity ought to be taken to make them easier and more enjoyable. On my solo of Grape Race/Tribal Rite in the spring, I had developed the idea that “if you’re manhandling something, you’re f*#king up”. John and I both have 2:1 hauling down to a fine art. In the summer, before leaving for Yosemite we had set up a hauling system in a large tree at his house. We practiced hauling and worked out the details of setting up the system quickly and making it as efficient as possible. I would say that 2:1 hauling has taken hauling off the table for us as far as big wall suffering goes. It’s still hard work, but it’s not gruesomely hard work. Docking tethers tied in Munter hitches are another technique that have taken a bite out of wall climbing, as they are easily tied and more importantly, easily untied.

All in all, these little techniques and tricks allow us to enjoy the actual climbing a lot more. Clothes are now lighter, warmer and more weather resistant. Warm sleeping bags are small and lightweight. Efficient and easy-to-use stoves have opened the door to warm and nutritious meals, not to mention big wall coffee. Throw modern portaledges and their flies into the mix, and you now have a big wall experience that doesn’t have to involve suffering.

John:

Launch Day Minus 1 was an easy day of guiding a friend up Higher Spire Regular Route. I felt strong and competent. But as night fell, my usual ghosts emerged. Around the campfire, I tried not to drink too much, but then I couldn’t sleep no matter how much I tried to relax. The 5AM wake-up call preyed on my nerves. I willed my mind to stop spinning, but no luck. The alarm buzzed me out of a short pre-dawn doze and after a cuppa joe, I failed the acid test of being a real big wall veteran: I couldn’t poop! I probably sat there on the crummy campground can reading the topo twenty times over. How many times can you look at a little line labelled “The Groove”? No luck. Not even a walnut. I have never - not once in 7 walls - pooped pre-launch. Nevertheless, off we went, up to Mammoth one last time and on to Gray Ledges.

Visit on gorge.net

Mark, on the other hand, can pretty much poop on demand. Bastard!

Visit on gorge.net

We’re blasting!

Mark:

A few days later, with our third and final load packed we awoke at 5 AM, had coffee and breakfast then drove to El Cap. The forecast predicted clear and warm weather for the next five days. Three hours later we had arrived on Mammoth with our final load of three, fully packed and ready to go. We easily had more than a couple hundred pounds of stuff but our 2:1 hauling system had made it casual.

Visit on gorge.net

Shorts, T-Shirt, Sunglasses, 2 to 1 hauling on El Cap, it doesn’t get any better!

From our high point a pitch above Mammoth, John took over the first aid lead while I laid back on the pigs enjoying the sun. Last year, John had been sick and had crawled up this pitch, but this time he was moving rapidly upwards, and I barely had time to get comfortable before he finished his lead. I led a short easy pitch and then John aided into a vile 5.8 flaring chimney that ends at Gray Ledges.

Visit on gorge.net

It’s really and truly 5.8 but it’s VILE!

Video: We have good attitudes!

I should set up a mailbox at Gray Ledges, I’ve spent five nights there over the years. My second night ever on El Cap was spent there, sharing the 2x5 foot ledge with Eric Sanford, shivering in our down jackets and cotton painters’ pants under a plastic tarp while it snowed and rained on us. Our friends in the Valley were, of course, yelling up the whole time that we were going to die. We rapped the next day.

But this time our evening was different, with warm food, cold beer, music and clear skies.

Visit on gorge.net

“You’re gonna die”! Mark trying to stay dry on Gray Ledges, Spring, 1974

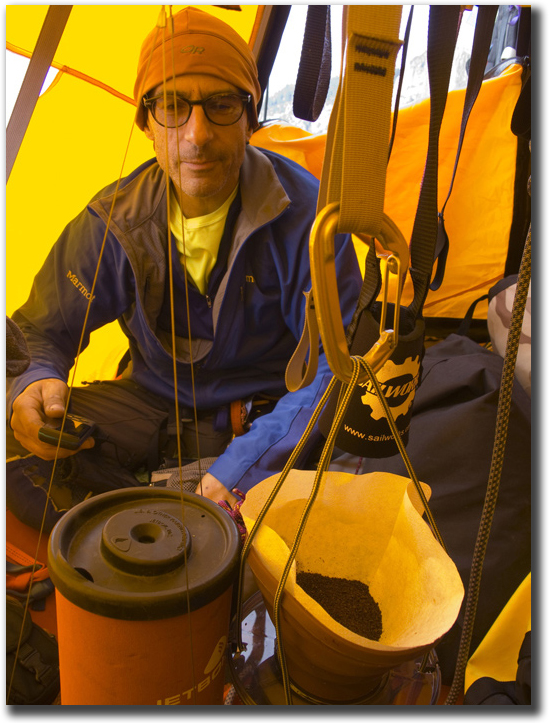

Before leaving Hood River, John and I had discussed the best way to make coffee on the wall. Earlier in the year, I had tried a small gold filter that fits into the cup, but I didn’t like the time it takes to brew or the sediment it leaves in the cup. I had bought a collapsible cone filter holder at the Mountain Shop in Yosemite, and had cut notches so that it fit snugly on top of my “Big Wall Coffee Cup”.

When John suggested coffee pods, I almost unfriended him on the spot.

Incidentally, everything was “Big Wall” on this trip – Big Wall Coffee Cup, Big Wall Pillow, Big Wall Sponge, Big Wall iPod, Big Wall Spoon. You can make an Anything into a Big Wall Anything, just add a clip-in loop. I had counted out enough filters and measured out enough coffee to last us for several days. I may be a wizened big wall climber with years of experience, I may be Mark Hudon and I may even be Badass, but being the guy who was doling out the coffee is what really sent my stature rising to the moon.

Visit on gorge.net

Coffee care of Hood River Coffee Co.

The next morning, I free climbed almost all of the 5.11c pitch above Gray Ledges, and then John set to work on the long, beautiful C2 corner above it. While belaying, I was happy to find that I was enveloped with the feelings of my solo in the spring, where “everything was important, yet nothing was important”. I was finally on the wall, and there were only so many places to go and only so many things to do. These days it seems, with cell phones, texting, email and the internet, every waking moment of our days could be taken up with “being productive”, “staying in contact” or “keeping up to date with the News.” Instead, being on the wall focuses your mind. You wonder, What’s important? What really matters? When you’re on the wall, life is simple – all you have to do is lead a pitch, clean a pitch, haul a pig, keep your partner safe, eat and sleep. In a way it feels like meditation to me, with all your extraneous thoughts eliminated.

Visit on gorge.net

Awesome corner!

I led the pitch to below the Shield Roof and John cleaned it enthusiastically, eager to take on the Roof. I set up my new Parke Belay Lounge, sort of an adjustable three quarters length single point hammock, and got comfortable for the show.

Visit on gorge.net

The Belay Lounge

John:

Even unrelieved, the 4-day Launch worked: I was left feeling strong and psyched climbing over the Shield Roof. This was, for me, the emotional crux of the route. After being unable to muster the energy last year to even move up at all on this pitch, I knew that failure here would be the end of everything: my wall partnership with Mark, probably my wall career, certainly my self esteem. I live down the street from Mark; the spectre of facing him shamefully year upon year made it easy to be unflinchingly focused on success. I had to go up.

I remembered how I felt the previous year. Mark had said (flat out - he didn’t ask), “We’re going down, aren’t we.”

I had to answer, “I can’t lead the Roof. I can’t haul, I don’t even know if I can follow.”

Mark paused, then said, “I can’t do it all alone.” You don’t ever want to be the guy who broke Superman. It was an awful thing to hear. The instant after you decide to bail, the very first instant that you take a bailing action, you feel as small as a mouse. As small as a speck of dirt.

So this time, Mark and I didn’t even chat at the belay below the Roof. I just said, “Gimme the gear,” and got above that shameful spot as fast as I could.

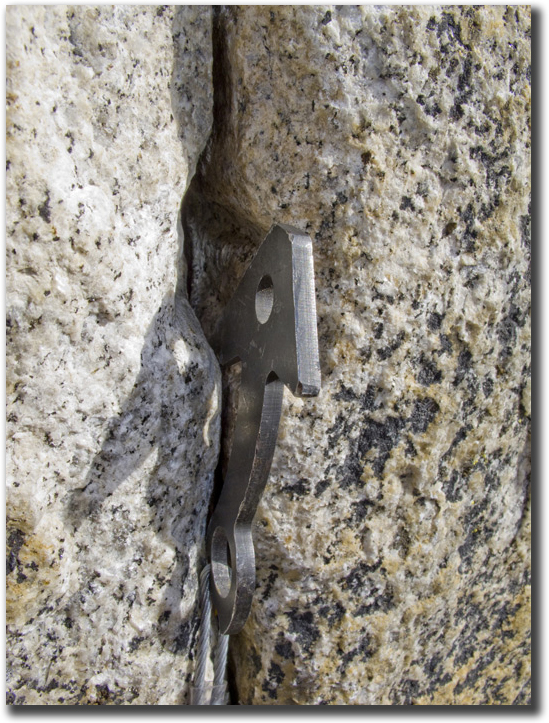

We had talked with the friendly Polish climber Regan at the bridge who had solo’d the Shield the year before. He mentioned that there was a blind nut placement at the lip of the Roof. This sounded spicy. When I got to the lip, however, I met an ugly-ass pin scar (the first of many) right on the edge - this was going to be my first sawed-off placement ever! Luckily, I had previously asked Mark how angle pitons were placed, so I understood that the pin goes in sideways, and that it was important to choose the size that would allow the backbone of the piton to touch the groove on one side of the scar while the two legs touched the two grooves on the other side. I tried a few sizes and found the one that fit. It slid in effortlessly and seemed snug. A hand-placed sawed-off at the airiest spot on the whole route, oh yeah. I yelled, “Hand-placed sawed-off!!” to let off a little stress, and then I stepped in my aider. To feel this piece lock into place was the defining moment of the whole adventure for me. As soon as my hips reached the Shield Headwall, I knew that I had swept another skeleton out of the closet. I whipped in a nice #4 HB in a pin scar, flaring and lots of gold showing but secure, got on it, then I reached down to the lip and pulled out the angle out by hand -- r-r-r-i-n-g

Video: At The Lip.

Look for the pinscar that will take my first-ever hand-placed sawed off.

Visit on gorge.net

John enjoying himself on the Roof.

Mark:

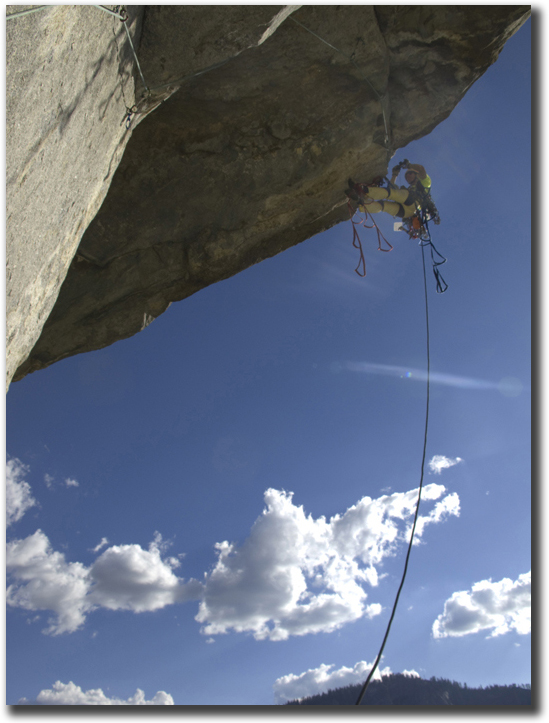

To tell you the truth, I’ve always been a bit freaked about getting up on the Shield headwall. It seems so vast and sweeping, so blank. Retreat appears almost impossible, and maybe the best way off in emergency would be upwards. But John was psyched and excited so I figured that I’d do the best I could to keep it together. I’ve done a bunch of hard aid walls in my day, the Magic Mushroom, The Mescalito, an early attempt on the PO, The Zodiac all in the first five or ten ascents. The routes were hard and I got up them in good style but I always thought I was faking it. I always thought that I had lucked out somehow. Maybe because I’ve never weighed more than 125 pounds, pieces that were “body weight” for other guys seemed pretty solid for me. On every wall I had ever done, at least once, I was totally scared shitless. I always managed to pull it off though, I got up the routes - maybe only by the skin of my teeth, but I got up them.

Visit on gorge.net

The Shield Roof. photo by Tom Evans

After John cleared the roof, I heard his shout of “Off belay!” and soon the haul line came tight. I cut the haul bags loose without lowering them out, and we both hooted and hollered as they went winging out into space. I found it easy to clean the pitch, which is mostly bolts, and before long we had finally gained the Shield Headwall. We bivied right there and celebrated.

Video: Cutting the Pigs loose.

Video: John and his pillow, BWP

Video: Weather coming in.

The next day, my first lead on the Headwall was the long, overhanging corner up to the base of the Groove. This pitch soars up perfect granite, undulating softly and accepting bomber nuts the whole way. I can’t say John seemed excited to start up the Groove, but he seemed determined and resolved. I was comfortable in the belay lounge and John moved upwards surprisingly quickly. At one point he stopped and yelled down for me to watch him as he was moving up on a rotten sling attached to a RURP. He got on the ratty tat, fiddled for a bit and then suddenly whipped fifteen feet! He told me that the sling had broken and that now he was putting a Beak on top of the slingless RURP. A few seconds later he fell again! This time, the Beak had pulled out the RURP. Once again he went back up, put the Beak in the RURP scar, and then he promptly fell again this time falling backwards and hitting his (helmeted) head.

Visit on gorge.net

John leading the Groove.

I was thinking, “Jesus Christ, John, whale in a frickin’ pin!” But no, not yet, I think he placed a small nut, which pulled, causing his fourth fifteen-foot fall in a row. Had it been me, by this time I would certainly have buried a pin or a beak. Even from my viewpoint far below at the anchor, anchored to all the bolts and safe in my belay lounge, I was pretty freaked!

So John goes back up there for a fifth time, and decides to nail. “Right on,” I’m thinking, “about friggen time!” I’m expecting to hear full-on whacks with his hammer, but what does he do? He taps a beak! He TAPS it ONCE! “Dang, John,” I thought, “you are the MAN!”

John:

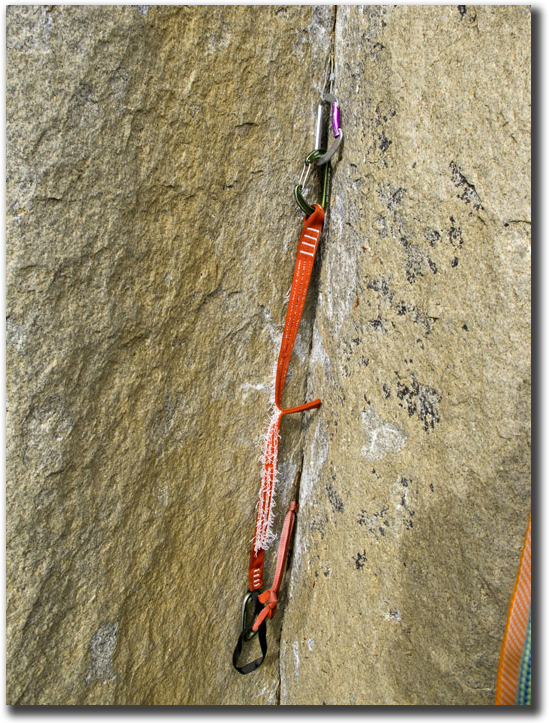

The hammer proved a sore temptation. Until the Groove pitch, I had never really swung the hammer. For the first half of the Groove, relying heavily on fixed gear, I just sailed along easily. But then I arrived at a fixed RURP whose original blownout wire was replaced with a grayed bit of webbing. A loop of better cord had been girth hitched onto the knot to serve as a clip-in point. Above was another RURP, but with a cable. The piece I was standing on was a good RURP.

I’ve always felt comfortable using crappy fixed gear (stupidity, this!), so without any fuss I clipped that puppy, tested it a bit (it stretched ominously), and started climbing. I got almost to my second step. “Aahhhh”, I sighed mentally, “I’m good.” But then I looked down - dammit, I had forgotten to collect my ladders from the previous piece. So down I climbed, and back up. That rotten piece of webbing passed right in front of my nose laughing at me 3 times. Almost there....then, silently, I was hanging 15 feet lower. The webbing had blown, as had the Screamer I had on the previous piece.

Visit on gorge.net

Drat that tat!

Visit on gorge.net

A Screamer having screamed.

Visit on gorge.net

The RURP that held the falls.

I got a bit amped up. My arse was hanging two thousand feet off the deck, off of an old copperhead! Mark was in sight, and I could see him watching closely. We gave each other the “Oh, sh#t...” look. I still had no thought of the hammer - it didn’t even occur to me. Back up and I pulled out the BLTs (Beak-Like-Things). I tried one on top of the RURP. Seemed good to me. Now I was inching ever so gingerly up my steps, 3rd step.....got my feet into the 2nd step, starting to stand up, and jangle! I was 15 feet down again, upside down, my rack tinkling around me like churchbells.

This time Mark asked, “Are you OK?” with some concern. I was a little shaken. I’ve had some bad upside-down falls over the years - I guess I’m top-heavy. I took a moment to right myself. Yes, only scraped up a bit. But now I was getting frustrated and scared. The adrenaline edge had worn off, and a bit of grim resolve had to take its place. Back to it.

Arriving at the RURP, I saw that it had vanished. The beak had pulled it out! I had not taken a stick with me (at Mark’s insistence), which had always been my tool to bypass previous A3-ish spots. It would’ve been the tool of choice here, but I see now that the battle for upward progress relying on only spit and bailing wire is sweet. Letting the stick steal this from me would have been a mistake. Grimly I stated, “Moving up.”

I tried hand placing a beak directly in the back of the Groove. There was a razor thin crack back there, but it had no “shelf” for the beak’s point to bite. Time after time, with different beak sizes, the point slid out when I weighted it the littlest bit. Frustration! I felt embarrassed to be moving so slowly in front of Dr. Fast, Mark Hudon.

I switched to cams. The groove of the Groove here was a smooth 70-degree flare. Placing a flexible cam sideways - pointing straight out - was my only hope. There was the faintest of bumps on the side of the groove on which a cam lobe might gain purchase. After some fiddling, I got a cam to sit in place on its own. I was horrified to be considering this placement, but still my mind was in “clean climbing” mode. I used the “ease on” technique of holding my good piece with one hand, while standing with one leg in a ladder on the good piece, and the other leg in a ladder on the poor piece. I eased my weight onto the new piece. It blew before I was even 50/50, and I used my holding hand like a human Screamer to absorb some of the energy of the tiny fall. I tried this 3 or 4 times, with bigger and smaller cams, but no dice. Nothing stuck. No progress. I was at a mental dead-end, worn out. Why oh why had I forgotten to collect my ladders the first time on that damned crap sh#t piece?

The “clean” door closed in my mind. Like a train lurching to a halt, then moving again in the opposite direction. I took a minute to rest, then yelled, “Using the hammer!” to Mark. This was unknown territory for me. What exactly was I supposed to do? Well, some things are so obvious, you just do them. I knew the theory. This was no A3 placement. I just held a beak in place and tapped it once, lightly - tink. Through the handle of the hammer I felt that beak set securely into the seam. I holstered the hammer and tried to pull the beak out with my hand. Not a wiggle - it was so bomber! I clipped an aider to it and got on it with “ease on”. It held. Jubilation! I wanted to hug that beak like a security blanket. I called down, “Moving up!” In my mind, the sun came out from behind a cloud. Everything changed for me, everything about wall climbing, for the rest of my life, right there. I felt so empowered by the hammer, like Thor the Thunder God - but there is a dark side to that power.

After that moment, I had to resist the urge to pull out the hammer whenever a piece looked sketchy. In fact, those were the last leader falls I took for the rest of the climb, and I did indeed swing the hammer 4 or 5 more times. When I got scared, more often than not, I whipped out the hammer and made C3 or 4 into A1. That first hammer swing of the trip was weightiest because it ruined the challenge of the team climbing a wall “clean”.

Visit on gorge.net

Vertical Freight Hauling

Mark:

From there on, John just rambled to the anchor, placing a few more beaks with a few gentle taps, no big deal. It seemed to me that John found his mettle on that pitch.

Me? Well, I’m another case altogether. I cleaned the pitch without thinking about it too much. The Triple Cracks were heavy on my mind, and the start didn’t disappoint me. Right off the anchor was a RURP with some thin little one mil cord strung through it, and above it even more crappy pieces. I was directly over top of the anchor and didn’t want to fall straight onto it and John, so the minute I got to a halfway decent placement I whaled something in, eventually hammering four pieces consisting of two beaks and two sawn angles.

Visit on gorge.net

Leading the Triple Cracks.

Visit on gorge.net

Only on the Shield.

John:

The whole mythology of “clean aid” is really just a fiction that makes the adventure seem measurable, makes a better story - just like the myth of pioneering the unknown. It mixes together the notions of preserving the rock and being willing to take some risk. Anybody who saw the sorry state of the pin scars on the headwall section of the Shield would want to clip fixed gear rather than hammering further damage into the rock. But fixed gear leaves me feeling both hot and cold. Certainly I was happy to be falling onto a good-looking fixed RURP on the Groove. If the Groove had been cleaned of every single fixed piece, would I have been happier? Looking back now, I'll claim the answer is "yes". At the time, I'm sure I would have shat my pants thinking about climbing it hammerless - some sections were so devoid of any semblance of a crack thicker than RURP size! Yes, I'm sure of it, clean of any fixed gear would've been the better experience. Climbing that pitch not just "clean", but "clean-clean", would have been a badge of honor I'd be proud to wear. (Not as proud as if it had never been altered by anyone's hammer at all, but that experience was meant for a generation earlier than ours).

But then there is the environmental preservation issue. If everyone swung the hammer with the same force, then you could say that it's acceptable to use hammered aid on the Groove. All metal Groove placements were either beaks in former RURP slots, or sawed off angles in giant square pin scars, both of which required just a light 'tap' to set. The pieces could sometimes even be removed by hand after having been set with a tap of the hammer. Surely this didn’t cause too much further damage to the stone. But who can guarantee that every climber taps lightly? One man's tap is another man's wallop. For that matter, who really can guarantee that even a light tap doesn't damage the rock *a little*? In fact, standing on even a hand-set sawed off probably enlarges its scar a bit.

Visit on gorge.net

Hmmm... can’t we get more creative than this?

To take this feeling a little further, if a fixed piece is removed from even an obvious crack, who is to guarantee that somebody, lacking the correct-sized cam or just scared witless, won't hammer in a piton in the future? Is it better to leave such a fixed piece in place? No, that's going too far. Cracks are meant for cams, aid climbing with cams and nuts is the heart of the leading experience for me, so I want obvious cracks to be clean. There has to be some balance.

If I were the guy making the rules:

• For the sake of the rock, clippable fixed gear in non-cammable placements should stay. Only one fixed piece per ladder-length - extras can be cleaned

• Fixed gear in cracks that could obviously take a cam should be removed

• Fixed gear placed by your leader should be removed by your follower, unless you’re replacing a required fixed piece where a clean placement won’t go

• The term "clean-clean" should be added to the aid-climbing lexicon, to mean "didn't swing the hammer, didn't clip any fixed gear"

Visit on gorge.net

Bomber and nice but certainly overkill.

Mark:

The anchor at the top of the Triple Cracks was the usual Shield affair of six or seven bolts. I thought back to reading Gary Bocarde’s article about the Shield’s first ascent and his fear of running out of bolts. He wrote that they had placed “usually only one bolt” at the belays. I clipped into all six of them and set up the anchor so the ledge hung on the right and the bags on the left to line up with the door on my fly. The evening before, our wives had informed us by cell phone that we had some bad weather coming in. The forecast was 70% chance of rain for the next few days, and we didn’t want to take any chances. In fact, we were actually happy at the thought of spending a storm day up here, and that we could enjoy another night hanging out on the mighty Shield headwall. We set up the ledge and fly, but left the fly in “quick deploy mode”. Good thing – at two in the morning it started to rain, so we jumped up and pulled the fly down and around the ledge. By the time we were finished, it had stopped raining, and we went back to sleep.

John:

Mark’s efficiency, speed, and expertise came to me as a welcome new challenge. In my ten years of walls, I had never climbed with anyone more experienced than myself. I was accustomed to making all of the battlefield decisions either solo or with a non-authority-figure partner. This time around, I felt the tremendous relief of being told, more often than not, what to do by Mark. Ah, the carefree life of the enlisted man! He told me how to set up his ledge quickly and how to properly deploy his assembly-free chongo ratchet from its stuff sack. He told me how to haul without a ratchet on the fixed lines and how to set the final haul at hip height on a summit tree. He hauled faster, cleaned faster, and led faster than me. If I finished cleaning a pitch before he finished hauling I gave myself a gold star. Same if I finished hauling before he arrived (I don’t think that ever happened). Each time I told Mark to do something that he hadn’t already thought of - big gold star. I think that my only technique contributions on the climb were the BWP (Big Wall Pillow) and the Big Wall Siphon (a 3 ft length of plastic tubing to siphon water from our unwieldy gallon jugs into a hand-sized 1.5 liter bottle - a magically easy Better Way technique). Oh, and for our weather day, Big Wall Poetry (so difficult to select the correct Big Wall Poetry for a wall, I always spend long hours pondering this decision). For the Shield I went with Paradise Lost by Milton, and Rime of the Ancient Mariner by Coleridge: "There was a ship," wrote Coleridge, and we were on it!

Visit on gorge.net

John leads out during a clear spell in the storm. photo by Tom Evans

Video: John needs coffee!

Mark:

By 9AM it was looking nice enough for John to get out and lead the next pitch. We didn’t know how long we would be stuck there so we figured we should get some climbing done whenever we could. I belayed from the door of the fly and John did a good job on the pitch, one tapping only a couple of pins or beaks. Just has he got to the anchor the weather turned cold, windy and looked threatening so he rapped back down to the ledge where we got the Stones’ “Some Girls” going on the Big Wall iPod and made some oatmeal and more coffee. Out came the Big Wall Poetry. John settled into decipher “Paradise Lost” and I to “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”. I shuddered when I thought of how Eric Barrett and I would have fared in this same situation back in ‘82.

Visit on gorge.net

Belaying from the door of the fly.

Visit on gorge.net

Just another day at the office.

Visit on gorge.net

Home Sweet Home photo by Tom Evans

John:

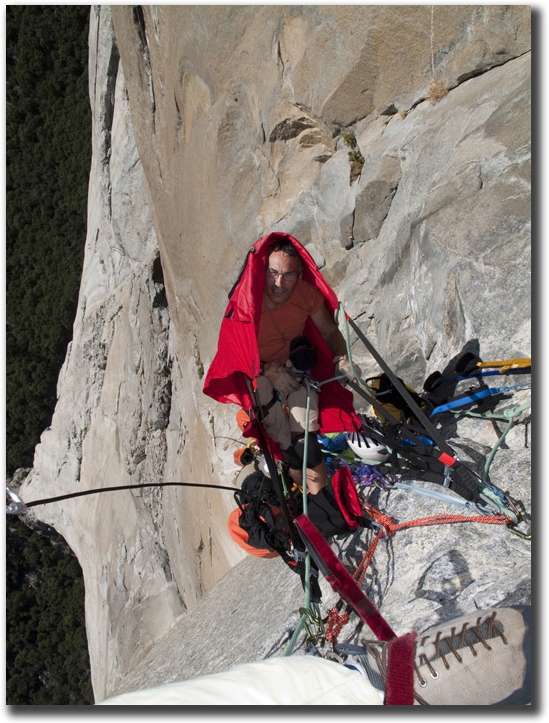

Mark’s bivy setup was another technique revelation for me. I had always feared a long bivy under the door-less, windowless A5 fly that came with my other partners’ ledge setups. I’m something of a claustrophobe, and every time I had practiced setting that fly I felt panicky underneath it. Mark’s fly, on the other hand, came complete with a little triangular “astronaut’s” window. Moreover he had gotten his fly modified with a big fat zipper to make a door, and had a little cloth shield installed at the peak of the fly so the door zipper could be left open at the top for ventilation, while still keeping rain out.

This little vent calmed me. Just knowing there was a little opening in the fly calmed me. In our sleeping positions, my head was pointed toward the door, giving me control of the zipper. So when the wind kicked up (it was sudden and violent), and it was time to batten down the hatches, I didn’t panic. I’ll admit that I felt tense. We were in a horrifically exposed position. We didn’t know what might happen. Tom Evans wrote about us that day on his blog, “They are not in the best of positions if the weather gets bad but I assume they have the necessities to weather any event.”

Visit on gorge.net

Aaah, a door, fresh air, I can relax...

I zipped us up. We looked around our little yellow world. The wind started to buffet us - we could feel the ledge move under us. The fly snapped back and forth. Mark said, “The ledge is too high - it isn’t filling out the bottom of the fly.” He sounded calm. I felt that I had to match his blood pressure, so I forced myself to reply *slowly*, “I’ll lower my side.”. “We have to get the ledge sitting against the reinforced area of the fly or we could damage it”. We each pulled ourselves up momentarily by the ledge straps and simultaneously slackened them. “OK, is that enough?” “No, lower.” 6 inches lower, the fly was taut. We looked at each other. We sat in silence. The wind came in pulses. I adjusted the fly tensioning pole to press out a baggy area that was snapping. Then, the wind stopped. Rain started to splatter. We laid down. Calm returned. We had done what we could. We called Pass The Pitons Pete on the radio and traded jokes. I was enduring my first ever bad weather bivy on El Cap quite enjoyably.

Video: Story In The Fog.

Visit on gorge.net

Is it coffee yet?

Mark

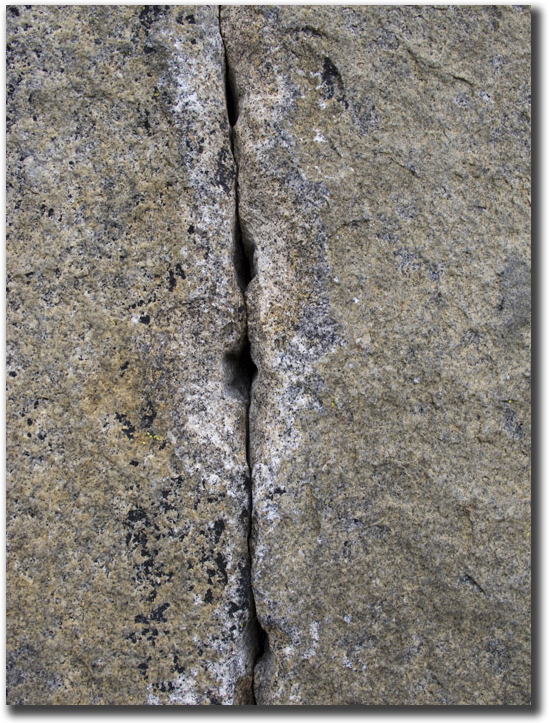

I had wanted to get up on the Shield headwall for a long time, and although the situation is unique and spectacular, the actual climbing is easily the most disgusting experience I’ve ever had on El Cap. The whole of the Shield is the most continuously and severely pinscarred crack in all of Yosemite and probably the world, even worse than the first pitch of Serenity Crack. Where Porter placed RURPs we now hand place large sawed-off angles and cams in huge square holes. A once beautiful thin crack is now a pockmarked pegboard. I felt ashamed to have hammered the four pieces I did. I looked down the Triple Cracks, and considered asking John if he would mind rapping down there and belaying me again so I could try to climb it cleanly.

Visit on gorge.net

This used to be an A5 RURP crack. Charlie Porter, what have we done?

It rained a bit more that afternoon and evening, but the next morning looked promising and we prepared to move on from where we had now spent two nights. Even though the topo showed my next pitch to be C4F – harder even than the Triple Cracks – I was determined to climb it clean. I can’t say it actually was any harder than the Triple Cracks though. Maybe I was more relaxed, more aware, or even more knowledgeable? This time I was able to feel comfortable hanging on hand-placed beaks and sawn angles. John and I started to joke that the new medium and large beaks ought to be illegal since they are so bomber in so many sketchy situations.

Visit on gorge.net

A bomber, hand placed beak.

After climbing this pitch clean, I felt a little better about myself, but then I sighed when I saw the horrendously scarred start to the pitch above Chickenhead Ledge. It went clean easily for me, and I was glad to be past it and up to the anchor and bivy on the long, narrow and sloping Chieftain Ledge.

Now high on the wall, and with the summit in sight, John and I were having a great time. By this time we were fully in synch setting up the big wall bivy program, and soon we were enjoying beers and BW martinis (Guiness mixed with a shot of gin - John’s drink of choice), making popcorn, listening to music, watching a beautiful sunset, laughing together and just enjoying being on the wall.

Visit on gorge.net

It doesn’t get much better than this!

Video: Big Wall High.

John:

The 2 pitches I linked above Chieftain (a whopping 65m lead!) were an unexpected no-hammer test. Placement after placement in the first 100 foot corner was in big ugly pin scars, all above a ledge. I wormed my way up my ladders, cursing the insecurity of the hand placed angles and trying not to pull outward. My corner aid technique sucked! Mark had just taught me the traditional “rest step” - a giant speed improvement as I had been relying totally on adjustable daisies - but it did me no good while stemming. 4 hours of worming, sweating, and “Watch Here!”’s later, spent, I had managed not to swing the hammer. But the game, as they say, isn’t over till the pig is on the summit.

Visit on gorge.net

John’s last lead. Close to 65 meters!

On the next pitch - the last real pitch - Mark and I finally hit the unknown. He was linking 2 pitches - a sideways lead out a roof followed by a long 5.7 chimney. To free climb without rope drag he chose to back clean the roof, after leaving some gear far below it. We had a very brief discussion, as in “We’ll figure it out”, “Yeah, no problem, you go” - before Mark took off leading. 50 feet up he called down, “You just jug up to the last piece I’m leaving here, then down-aid until you can safely lower-out.” “Sure, no problem,” I called back, “It’ll be fine.” By the time he finished leading the roof sideways, the rope angled from his last piece with ominous acuteness of angle.

Visit on gorge.net

Have fun cleaning this pitch, John!

But I wasn’t worried. We had just spent 5 days getting dialed in with technique. I was confident! Yeah, that seemed like the best idea. Down-aid. I jugged up to his last piece - a small cam, now being pulled sideways by the tensioned rope - and gulped as I looked at the fearsome swing I’d take were it to pop. “Goddammit, John, just get going, every foot down is safer”, I muttered to myself as I began down-aiding. I couldn’t even complain to Mark as he was out of sight and hearing.

As soon as I started down, I realized that Mark had backcleaned pieces below as well, so I had to re-place an intermediate nut to make it from one piece to the next. I didn’t have the right piece, so I made do. Downaiding is awkward especially when the pieces are far apart, because you need a little more reach to remove a nut above you than to place it. Just as I was standing in the bottom step of my ladders, all crunched up, struggling to step into the top step of the ladders below, swearing like a sailor, I heard that distinct sound, the one you never forget - plink! Suddenly I was shot off like a rocket. Upside down and sideways into space. No sense of up or down. Complete disorientation. 3000 feet off the deck.

I really like control. So when I lose it, I go totally ballistic. Ask my wife how horrible it sounds when I puke. Well this was one of those “I’m puking” times, but worse. Here I was, tumbling sideways into space and swinging upside-down across the face. I really let loose screaming. Not a “oh sh#t, this is bad” scream but a savage howl, like my legs were being amputated and I was certain that I was in the middle of dying. Truly I didn’t know if I was still connected to the rope, or in freefall. “Aaaauuuuuuuuggggggggghhhhhhaaaaaiiiiiiiieeeeeeeee!!!!!” Damn, I used to hate it when my mom screamed at me like that, and now here I was, just like her. I must’ve gone on like that for an eternity.

Video: John survived but he has gas!

During the swing I smashed the wall pretty hard with my elbow so I screamed some more (I have a nice bone spur there now). Once I stopped moving, I hung for a while, collected my wits, and assessed the damage. Still dangling from the rope, which looked undamaged - that was good. My arm hurt but I could move it. No spurting blood - that meant we were going up. OK. Emotionally, I was done for the moment. 100 feet above, Mark popped his head out of the chimney and called down to check on me. How was I? “Not sure, I hurt my arm.” Slowly, painfully, I clamped my ascender on the rope (good thing only the grigri was on the rope when I popped since this was perilously close to a leader fall during which an ascender could have cut the cord) and inched my way up to the belay. Poor Mark - he was more shaken than I was. You’re not supposed to scream like you’re dying unless you are, in fact dying.

Topping off the day, the climb, the whole experience, was Mark saying, dead pan, “Your lead!” This was the summit pitch. A few moves of 5.7 followed by a bunch of 4th class. But I was wearing my floppy wall five tennies. The rock was slick, and my psyche sucked! I climbed up a few feet, then down. sideways a few feet, then back. I couldn’t face falling off the edge of El Capitan. But Mark, to his credit, calmly waited me out. I whimpered a bit, hemmed a bit, then sent the ferocious single 5.7 step and arrived on easy terrain. I looked at Mark with a sheepish grin and said, “I suck!” But I knew, and I knew that he knew, that wasn’t true.

On the Shield, I broke on through to the other side; I joined the ranks of wall climbers who take it slow and easy. I think I want to spend a whole day on each wall in a single, hyper-exposed spot, just relaxing and taking in the view. Too little of my climbing life is left to rush through walls any more; what awaits on top is nothing more than an awful hike down and a long drive home.

Our ascent was the first wall for me (out of eight all told) that didn’t feel like constant war. We had a few moments, but the overall tone was lazier, more civilized. No midnight pitches or paralyzing chaos. Plenty of time hanging out on our ledge. I credit Mark’s big wall techniques for this (heavily informed by Pass The Pitons Pete), plus our decision to take the necessary food, water, and attitude so we never had to rush. Except for the descent, I never once exhausted myself by using all my strength or working for longer than my body could handle. A very nice, “I’m fifty years old and don’t need that hero crap anymore” experience.

Mark:

A few weeks later, at a brewpub in Hood River, John and I discussed our next route. We looked at Zenyatta Mondatta and decided to do it, feeling that we needed to take a step up in route difficulty. We played around with who gets to lead which pitch and how many to fix and so on. I pointed out to John that if we fixed two and then climbed three pitches a day after that, the route would take us 4 and a half or 5 days.

John sipped his beer and studied the topo.

“Don’t you think we can stretch that to seven days?” was all he said.

Video: We are blessed

Visit on gorge.net

We may be old, but we ain’t dead yet!

Click here to view all the photos we took.

Video: A 5 minute compilation of all the videos.